Contempt proceedings begun against the Standard in Ohio in 1897 for not obeying the court's order of 1892 to dissolve the trust — Suits begun to oust four of the Standard's constituent companies for violation of Ohio anti-trust laws — All suits dropped because of expiration of Attorney-General Monnett's term — Standard persuaded that its only corporate refuge is New Jersey — Capital of the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey increased, and all Standard Oil Business taken into new organisation — Restriction of New Jersey law small — Profits are great and Standard's control of oil business is almost absolute — Standard Oil Company essentially a realisation of the South Improvement Company's plans — The crucial question now, as always, is a transportation question — The trust question will go unsolved so long as the transportation question goes unsolved — The ethical questions involved.

Few men in either the political or industrial life of this country can point to an achievement carried out in more exact accord with its first conception than John D. Rockefeller, for both in purpose and methods the Standard Oil Company is and always has been a form of the South Improvement Company, by which Mr. Rockefeller first attracted general attention in the oil industry. The original scheme has suffered many modifications. Its most offensive feature, the drawback on other people's shipments, has been cut off. Nevertheless, to-day, as at the start, the purpose of the Standard Oil Company is the purpose of the South Improvement Company the regulation of the price of crude and refined oil by the control of the output; and the chief means for sustaining this purpose is still that of the original scheme—a control of oil transportation giving special privileges in rates.

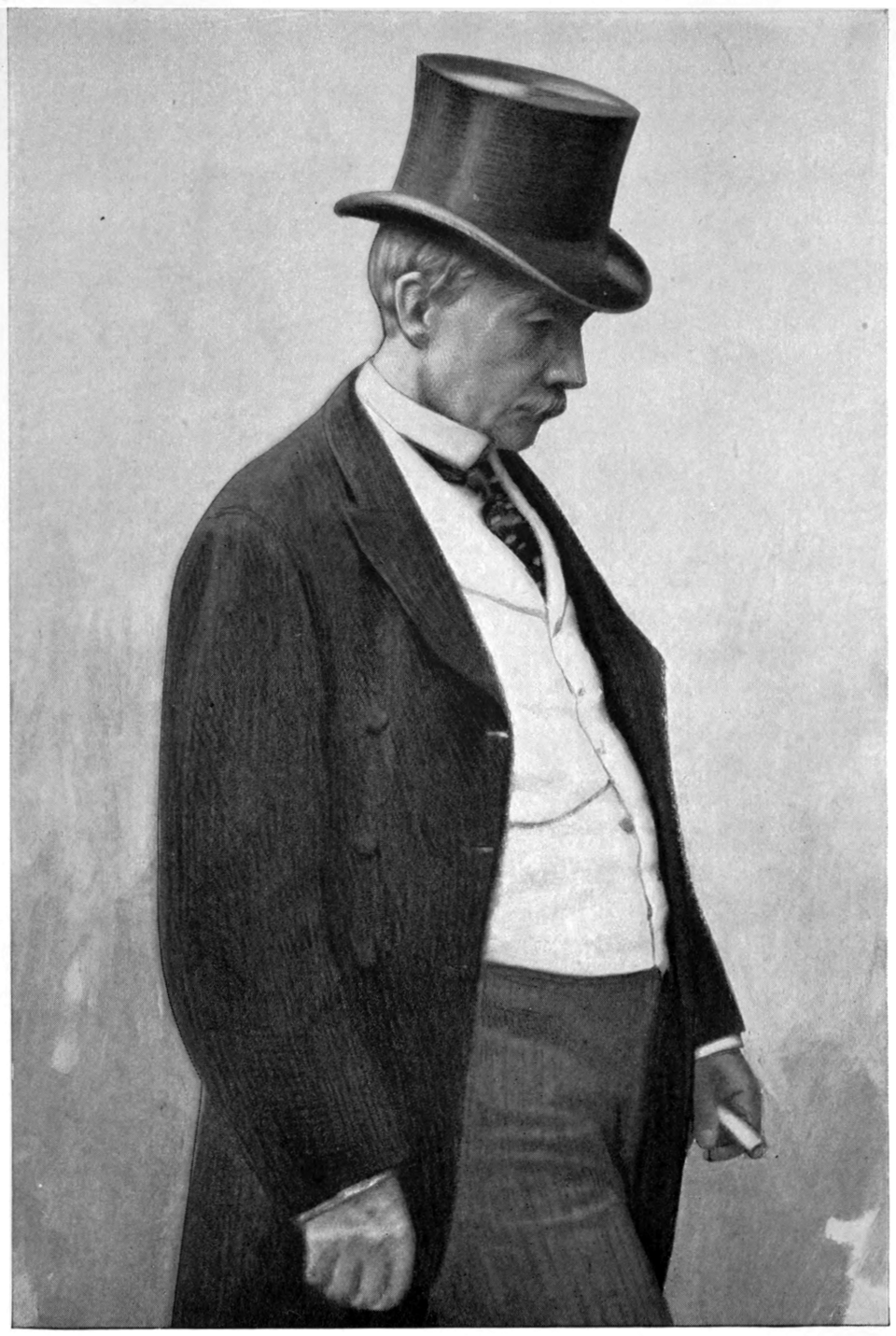

From a photograph by Allen Ayrault Green, taken about 1892.

It is now thirty-two years since Mr. Rockefeller applied the fruitful idea of the South Improvement Company to the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, a prosperous oil refinery of Cleveland, with a capital of $1,000,000 and a daily capacity for handling 1,500 barrels of crude oil. And what have we as a result? What is the Standard Oil Company to-day? First, what is its organisation? It is no longer a trust. As we have seen, the trust was obliged to liquidate in 1892. It became a "trust in liquidation," and there it remained for some five years. It seemed to have come into a state of stationary liquidation, for at the end of 1892 477,881 shares were uncancelled; at the end of 1896 the same number were out. The situation of the great corporation was indeed curious. There began to be comments on it, for complications arose—one over taxes. In 1893 an auditor in Ohio tried to collect taxes on 225 shares of the Standard Oil Trust. The owner refused to pay and took the case into court. He won it. The Standard Oil Trust is an unlawful organisation, said the court. Its certificates have no validity. It would seem strange that a certificate which was void to all purpose would still be valid as to taxable purposes.[1] Here was an anomaly indeed. The certificates were drawing big quarterly dividends, had a big market value, but were illegal. Owners of small certificates naturally refused to exchange. In 1897 it took 194½ shares in the Standard Oil Trust to bring back one share in each of the twenty companies. Thus one share in the Standard Oil Company of Ohio was worth twenty-seven shares in the Standard Oil Trust. If a man owned twenty-five shares he got only fractional parts of a share in each company. On these fractional parts he received no dividends, it not being considered practical to consider such small sums. To raise his twenty-five shares to 194, and so secure dividends, took a good sum of money, since Standard Oil Trust shares were worth at least 340 then. But why should he trouble? He received his quarterly dividends promptly, and they were large! He paid no taxes, for his stock was illegal! The trustees were not pushing him to liquidate. Besides, it was doubtful if they could do anything. Joseph Choate said they could not. On May 3, 1894, before the attorney-general of New York, in an application for the forfeiture of the charter of the Standard Oil Company of New York, Mr. Choate said:

"I happen to own 100 shares in the Standard Oil Trust, and I have never gone forward and claimed my aliquot share. Why not? Because I would get ten in one company, and ten in another company, and two and three-fifths in another company.

"There is no power that this company can exercise to compel me and other indifferent certificate holders, if you please, to come forward and convert our trust certificates."

If there was a way, the trustees were indifferent to it. They evidently were contented to let things alone. It is quite possible that they would have been holding to-day 477,881 uncancelled shares of Standard Oil Trust if it had not been for the irrepressible George Rice. Since October, 1892, Mr. Rice had held a Standard Oil Trust certificate for six shares. He had never cancelled it. He had received no invitation to do so. He received his dividends regularly on it. Later, he purchased one share, called "assignment of legal title"—the new form given the trust certificate—and on this he received dividends, exactly as on the original trust certificate. Finally Mr. Rice made up his mind, without knowing any of the facts of the liquidation outlined above, that there was no intention to carry out the dissolution, that some means of evasion had been devised, and he proposed to find out what it was.

To do this he transferred his assignment of legal title to an agent with the order to liquidate it. A long correspondence followed between Mr. Kemper, Mr. Rice's agent, and Mr. Dodd, who objected to making the transfer on the ground that it cut the share into a "multitude of almost infinitesimal fractions of corporate shares." They were obviating this difficulty, Mr. Dodd said, by purchasing certificates calling for one or a few shares and uniting them until sufficient were had by one party to call for the issue of full corporate shares. Mr. Kemper insisted, however, and finally received scrip for his share. "Infinitesimal" it was, indeed, 5,000⁄972,500 of one share in one company, 10,000⁄972,500 of one share in another, and so on through nineteen constituent companies.[2]

Arguing from these experiences and what else he could gather, Mr. Rice decided that the trust was not dissolved and had no intention of doing so. Furthermore, he argued that the scheme was one to entice the small shareholders to sell their shares and thus enable the trustees to increase their holdings! And he sought legal counsel in Ohio as to the possibility of bringing suit against the Standard Oil Company of Ohio for failing to obey the court's orders in March, 1892. The attorneys, one of whom was Mr. Watson, advised Mr. Rice to lay his facts before the attorney-general of the state, Frank S. Monnett. Like Mr. Watson, when he brought his suit, Mr. Monnett was young and held firmly to the belief that the business of an attorney-general is to enforce the laws. The facts Mr. Rice and his counsel laid before him seemed to him to indicate that the Standard Oil Company of Ohio had taken advantage of the leniency of the court in allowing it time to disentangle itself from the trust, and had devised a skilful plan to evade the judgment pronounced against it five years before. He asked Mr. Rice and his attorneys to go with him and lay the case before the judges of the Supreme Court in chambers, and ask if it did not justify proceedings against the company. The judges agreed with the attorney-general and ordered him to bring the company before the court for contempt. Information was filed in November, 1897. The suit which followed proved one of the most sensational ever instituted against the Standard Oil Combination.

The first substantial point gained by the attorney-general in the proceedings was securing answers to a long series of questions concerning the history of the operations of the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, both within and without the trust. These answers were made by the president of that company, who was at the same time the president of the trust, John D. Rockefeller. They furnish a mass of facts of value and interest, and they include the minutes of the meeting at which the trust was dissolved on March 11, 1892, as well as the minutes of all the quarterly meetings the liquidating trustees held from 1892 to October, 1897. It was from the information obtained from this set of questions that Mr. Monnett secured proof that the liquidation scheme had been held up, as Mr. Rice claimed. The minutes showed, as related in Chapter XIV, that from November, 1892, to March, 1896, 477,881 shares were reported every three months to the trustees as uncancelled. In July, 1896, the number fell suddenly to 477,880. George Rice had succeeded in having his assignment of legal title liquidated! Mr. Monnett learned from the result of this inquiry another suggestive fact, that while only one share was cancelled in the five years before the contempt proceedings were brought, in the first three months after, 100,583 shares were cancelled![3]

It took Mr. Monnett some six months to secure the answers from Mr. Rockefeller, but his information was still incomplete, and he asked the court to appoint a master commissioner, with power to examine the officers, affairs and books of the Standard, to take testimony within or without the state, and to report. This was done, the commissioner holding his first court at the New Amsterdam Hotel, in New York, on October 11 and 12, 1898. Mr. Rockefeller was the only witness examined at the sessions, and his deliberation and self-control, his almost detached attitude as a witness, were the subject of remark by more than one observer. He answered no question promptly. He had the air of reflecting always before he spoke. He consulted frequently with his counsel. His counsel, his colleagues who were present, the counsel of the prosecution, were sometimes irate, never Mr. Rockefeller. From beginning to end he was the soul of self-possession. His only sign of impatience—if it was impatience—was an incessant slight tapping of the arm of his chair with his white fingers.

The outcome of this examination of Mr. Rockefeller was that Mr. Monnett and his colleagues called for those books of the trust which would show exactly how the original trust certificates had been liquidated. It was then that the copies of the transfers of Mr. Rockefeller's trust certificates and of his assignments of legal title printed in the Appendix, Number 54, were obtained. Although Mr. Monnett had added to his knowledge of the Standard's operations between 1892 and 1898, he was not yet convinced that the Standard Oil Company of Ohio was conducting its own business. He had found that, in spite of the order of the court in 1892, 13,593 shares of that company's stock were still outstanding in trust certificates. He knew these certificates drew dividends. Was the company paying money directly or indirectly to the liquidating trustees? They said no, that they had been paying no dividends since 1892, that the money paid the holders of trust certificates came from the other nineteen companies, that all their earnings had been used in improving their plant, or were invested in government bonds. Besides, said they, we are not the thrifty concern we used to be. Mr. Monnett demanded proof from their books. The secretary of the company, on advice of his counsel, Virgil P. Kline, refused to produce the books asked for, on the ground that they would incriminate the company. The court supported Mr. Monnett, and ordered the company to produce those of their records showing the gross earnings since 1892, and what had been done with them. The order met with a second refusal.

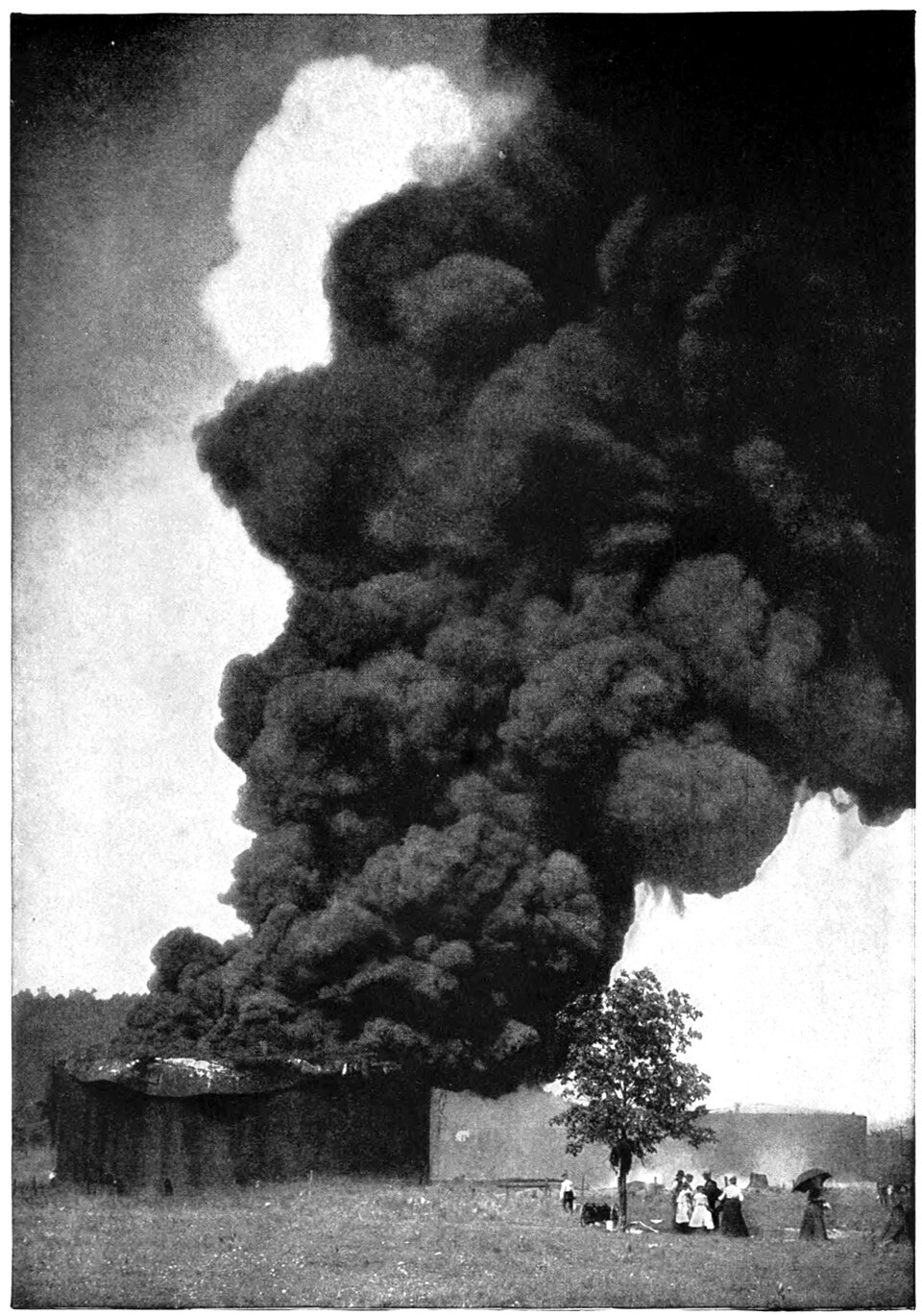

Such was the status of the proceedings when Mr. Monnett received an anonymous communication stating that, about the time the company was ordered by the court to produce its records, a great quantity of books had been taken from the Standard's office in Cleveland and burned. An investigation was at once made by the attorney-general, and a number of witnesses examined. The fact of the burning of sixteen boxes of books from the Standard offices in Cleveland was established, but these books, the officers of the company contended, were not the ones wanted by Mr. Monnett. "Then produce the ones we want," ordered the court. But, on the ground that such records might incriminate them, the officers still refused.

The fact was, the Standard Oil Company of Ohio was in a very tight place, and it is difficult to see how an examination of their books could have failed to incriminate not only it, but three other of the constituent companies of the trust which held charters from the same state. These three companies were the Ohio Oil Company, which produced oil; the Buckeye Pipe Line, which transported it; and the Solar Refining Company, which refined it. Mr. Monnett had learned enough about these organisations in the course of his investigations since November, 1897, to convince him that these companies—all of them enormously profitable—were, for all practical purposes, one and the same combination, and that they were all working with the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, and that their operations were in direct violation of a state anti-trust law recently passed. As soon as he had sufficient evidence he had filed petitions against all four of them. Now, these petitions were filed about the time he demanded the books showing the earnings of the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, for use in his contempt case. It was the old story of one suit being used as a shield in another. A witness cannot be made to incriminate himself.

The reasons F. B. Squire, the secretary of the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, gave for refusing to produce the books as ordered by the court were as follows:

1st. Because they are demanded in an action instituted against the Standard Oil Company for contempt of court, and for the purpose of proving said company guilty of contempt in order that the penalties for contempt may be inflicted upon it and its officers; and I am informed that, to enforce their production in such a case and for such a purpose, is an unreasonable search and seizure.

2nd. Because the books disclose facts and circumstances which may be used against the Standard Oil Company, tending to prove it guilty of offences made criminal by an act of the Legislature of Ohio, passed April 19, 1898, entitled "An Act to define trusts and to provide for criminal penalties, civil damages, and the punishment of corporations," etc.

3rd. Because they disclose facts and circumstances which may be used against myself personally as an officer of said company, tending to prove me guilty of offences made criminal by the act aforesaid.[4]

All through the winter of 1898 and 1899, up to the end of March, when the commission declared the taking of testimony closed, the wrangle over the production of the books went on. Depositions had begun to be taken at the same time in the cases against the constituent companies for violation of the anti-trust laws, and by the time the contempt case was closed in March, 1899, the exasperation of both sides had reached fever pitch. Nor did the judgment of the court quiet it, for three judges voted for finding the company guilty of contempt, and three for clearing it.

Unsatisfactory as this was, Mr. Monnett still had his anti-trust suits, through which he expected and through which he did secure much further evidence that the four Standard companies in Ohio were practically one concern so shrewdly and secretly handled that they were evading not only the laws of the state, but that policy of all states which decrees that it is unsafe to allow men to work together in industrial combinations without charters defining their privileges, and subjecting them to reasonable examinations and publicity. Mr. Monnett's work on these suits came to an end with the expiration of his term in January, 1900, and the suits were suppressed by his successor, John M. Sheets! Unfinished as they were, they were of the greatest value in dragging into the light information concerning the methods and operations of the Standard Oil Combination to which the public has the right, and which it must digest if it is to succeed in working out a legal harness for combinations which, like the Standard, demand freedom to do what they like and do it secretly.

The only refuge offered in the United States for the Standard Oil Trust in 1898, when the possibility arose by these suits of the state of Ohio taking away the charters of four of its important constituent companies for contempt of court and violation of the anti-trust laws of the state, lay in the corporation law of the state of New Jersey, which had just been amended, and here it settled. Among the twenty companies which formed the trust was the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, a corporation for manufacturing and marketing petroleum products. Its capital was $10,000,000. In June, 1899, this capital of $10,000,000 was increased to one of $110,000,000, and into this new organisation was dumped the entire Standard aggregation. The old trust certificates outstanding and the assignments of legal title which had succeeded them were called in, and for them were given common stock of the new Standard Oil Company. The amount of this stock which had been issued, in January, 1904, when the last report was made, was $97,448,800. Its market value at that date was $643,162,080. How it is divided is of course a matter of private concern. The number of stockholders in 1899 was about 3,500, according to Mr. Archbold's testimony to the Interstate Commerce Commission, but over one-half of the stock was owned by the directors, and probably nearly one-third was owned by Mr. Rockefeller himself.

The companies which this new Standard Oil Company has bought up with its stock are numerous and scattered. They consist of oil-producing companies like the South Penn Oil Company, the Ohio Oil Company, and the Forest Oil Company; of transporting companies like the National Transit Company, the Buckeye Pipe Line Company, the Indiana Pipe Line Company, and the Eureka Pipe Line Company; of manufacturing and marketing companies like the Atlantic Refining Company of Pennsylvania, and the Standard Oil Companies of many states—New York, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Iowa; of foreign marketing concerns like the Anglo-American Company. In 1892 there were twenty of these constituent companies. There have been many added since, in whole or part, like gas companies; new producing concerns, made necessary by developments in California, Kansas and Texas; new marketing concerns for handling oil directly in Germany, Italy, Scandinavia and Portugal. What the total value of the companies owned by the present Standard Oil Company is it is impossible to say. In 1892, when the trust was on trial in Ohio, it reported the aggregate capital of its twenty companies as $102,233,700, and the appraised value was given as $121,631,312.63; that is, there was an excess of about $19,000,000.

In 1898, when Attorney-General Monnett of Ohio had the Standard Oil Company of the state on trial for contempt of court, he tried to find out from Mr. Rockefeller what the surplus of each of the various companies in the trust was at that date. Mr. Rockefeller answered: "I have not in my possession or power data showing… the amount of such surplus money in their hands after the payment of the last dividends." Then Mr. Rockefeller proceeded to repeat as the last he knew of the value of the holdings of the trust the list of values given six years before.[5] This list has continued to be cited ever since as authoritative. There is a later one, whether Mr. Rockefeller had it in his "possession or power," or not, in 1898. It is the last trustworthy valuation of which the writer knows, and is found in testimony taken in 1899, in a private suit to which Mr. Rockefeller was party. It is for the year 1896. This shows the "total capital and surplus" of the twenty companies to have been, on December 31 of that year, something over one hundred and forty-seven million dollars, nearly forty-nine millions of which was scheduled as "undivided profits."[6] Of course there has been a constant increase in value since 1896.

The new Standard Oil Company is managed by a board of fourteen directors.[7] They probably collect the dividends of the constituent companies and divide them among stockholders in exactly the same way the trustees of 1882 and the liquidating trustees of 1892 did. As for the charter under which they are operating, never since the days of the South Improvement Company has Mr. Rockefeller held privileges so in harmony with his ambition. By it he can do all kinds of mining, manufacturing, and trading business; transport goods and merchandise by land and water in any manner; buy, sell, lease, and improve lands; build houses, structures, vessels, cars, wharves, docks, and piers; lay and operate pipe-lines; erect and operate telegraph and telephone lines, and lines for conducting electricity; enter into and carry out contracts of every kind pertaining to his business; acquire, use, sell, and grant licenses under patent rights; purchase, or otherwise acquire, hold, sell, assign, and transfer shares of capital stock and bonds or other evidences of indebtedness of corporations, and exercise all the privileges of ownership, including voting upon the stocks so held; carry on its business and have offices and agencies therefor in all parts of the world, and hold, purchase, mortgage, and convey real estate and personal property outside the state of New Jersey. These privileges are, of course, subject to the laws of the state or country in which the company operates. If it is contrary to the laws of a state for a foreign corporation to hold real estate in its boundaries, a company must be chartered in the state. Its stock, of course, is sold to the New Jersey corporation, so that it amounts to the same thing as far as the ability to do business is concerned. It will be seen that this really amounts to a special charter allowing the holder not only to do all that is specified, but to create whatever other power it desires, except banking.[8] A comparison of this summary of powers with those granted by the South Improvement Company shows that in sweep of charter, at least, the Standard Oil Company of to-day has as great power as its famous progenitor.[9]

The profits of the present Standard Oil Company are enormous. For five years the dividends have been averaging about forty-five million dollars a year, or nearly fifty per cent. on its capitalisation, a sum which capitalised at five per cent. would give $900,000,000. Of course this is not all that the combination makes in a year. It allows an annual average of 5.77 per cent. for deficit, and it carries always an ample reserve fund. When we remember that probably one-third of this immense annual revenue goes into the hands of John D. Rockefeller, that probably ninety per cent. of it goes to the few men who make up the "Standard Oil family," and that it must every year be invested, the Standard Oil Company becomes a much more serious public matter than it was in 1872, when it stamped itself as willing to enter into a conspiracy to raid the oil business—as a much more serious concern than in the years when it openly made warfare of business, and drove from the oil industry by any means it could invent all who had the hardihood to enter it. For, consider what must be done with the greater part of this $45,000,000. It must be invested. The oil business does not demand it. There is plenty of reserve for all of its ventures. It must go into other industries. Naturally, the interests sought will be allied to oil. They will be gas, and we have the Standard Oil crowd steadily acquiring the gas interests of the country. They will be railroads, for on transportation all industries depend, and, besides, railroads are one of the great consumers of oil products and must be kept in line as buyers. And we have the directors of the Standard Oil Company acting as directors on nearly all of the great railways of the country, the New York Central, New York, New Haven and Hartford, Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul, Union Pacific, Northern Pacific, Delaware, Lackawanna and Western, Missouri Pacific, Missouri, Kansas and Texas, Boston and Maine, and other lesser roads. They will go into copper, and we have the Amalgamated scheme. They will go into steel, and we have Mr. Rockefeller's enormous holdings in the Steel Trust. They will go into banking, and we have the National City Bank and its allied institutions in New York City and Boston, as well as a long chain running over the country. No one who has followed this history can expect these holdings will be acquired on a rising market. Buy cheap and sell high is a rule of business, and when you control enough money and enough banks you can always manage that a stock you want shall be temporarily cheap. No value is destroyed for you—only for the original owner. This has been one of Mr. Rockefeller's most successful manoeuvres in doing business from the day he scared his twenty Cleveland competitors until they sold to him at half price. You can also sell high, if you have a reputation of a great financier, and control of money and banks. Amalgamated Copper is an excellent example. The names of certain Standard Oil officials would float the most worthless property on earth a few years ago. It might be a little difficult for them to do so to-day with Amalgamated so fresh in mind. Indeed, Amalgamated seems to-day to be the worst "break," as it certainly was one of the most outrageous performances of the Standard Oil crowd. But that will soon be forgotten! The result is that the Standard Oil Company is probably in the strongest financial position of any aggregation in the world. And every year its position grows stronger, for every year there is pouring in another $45,000,000 to be used in wiping up the property most essential to preserving and broadening its power.

And now what does the law of New Jersey require the concern which it has chartered, and which is so rapidly adding to its control of oil the control of iron, steel, copper, banks, and railroads, to make known of itself? It must each year report its name, the location of its registration office, with name of agent, the character of its business, the amount of capital stock issued, and the names and addresses of its officers and directors!

So much for present organisation, and now as to how far through this organisation the Standard Oil Company is able to realise the purpose for which it was organised—the control of the output, and, through that, the price, of refined oil. That is, what per cent. of the whole oil business does Mr. Rockefeller's concern control. First as to oil production. In 1898 the Standard Oil Company reported to the Industrial Commission that it produced 35.58 per cent. of Eastern crude—the production that year was about 52,000,000 barrels.[10] (It should be remembered that it is always to the Eastern oil fields—Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, West Virginia—that this narrative refers. Texas, Kansas, Colorado and California are newer developments. These fields have not as yet been determining factors in the business, though Texas particularly has been a distributing factor.) But while Mr. Rockefeller produces only about a third of the entire production, he controls all but about ten per cent. of it; that is, all but about ten per cent. goes immediately into his custody on coming from the wells. It passes entirely out of the hands of the producers when the Standard pipe-line takes it. The oil is in Mr. Rockefeller's hands, and he, not the producer, can decide who is to have it. The greater portion of it he takes himself, of course, for he is the chief refiner of the country. In 1898 there were about twenty-four million barrels of petroleum products made in this country.[11] Of this amount about twenty million were made by the Standard Oil Company; fully a third of the balance was produced by the Tidewater Company, of which the Standard holds a large minority stock, and which for twenty years has had a running arrangement with the Standard. Reckoning out the Tidewater's probable output, and we have an independent output of about 2,500,000 in twenty-four million. It is obvious that this great percentage of the business gives the Standard the control of prices. This control can be kept in the domestic markets so long as the Standard can keep under competition as successfully as it has in the past. It can be kept in the foreign market as long as American oils can be made and sold in quantity cheaper than foreign oils. Until a decade ago the foreign market of American oils was not seriously threatened. Since 1895, however, Russia, whose annual output of petroleum had been for a number of years about equal in volume to the American output, learned to make a fairly decent product; more dangerous, she had learned to market. She first appeared in Europe in 1885. It took ten years to make her a formidable rival, but she is so to-day, and, in spite of temporary alliances and combinations, it is very doubtful whether the Standard will ever permanently control Russian oil.

In 1899 Mr. Archbold presented to the Industrial Commission a most interesting list of foreign corporations and individuals doing an oil business in various countries. According to this there were more than a score of large concerns in Russia, and many small ones. The aggregate capitalisation shown by Mr. Archbold's list was over forty-six and a half millions, and the capitalisation of a number of the concerns named was not given. In Galicia, four companies, with an aggregate capital of $3,775,100, and in Roumania six large companies, with an aggregate capital of $12,500,000, were reported. Borneo was shown to have nearly three millions invested in the oil fields; Sumatra and Java each over twelve millions. Since this report was made these companies have grown, particularly in marketing ability. In the East the oil market belonged practically to the Standard Oil Company until recently. Last year (1903), however, Sumatra imported more oil into China than America, and Russia imported nearly half as much.[12] About 91,500,000 gallons of kerosene went into Calcutta last year, and of this only about six million gallons came from America. In Singapore representatives of Sumatra oil claim that they have two-thirds of the trade.

Combinations for offensive and defensive trade campaigns have also gone on energetically among these various companies in the last few years. One of the largest and most powerful of these aggregations now at work is in connection with an English shipping concern, the Shell Transport and Trading Company, the head of which is Sir Marcus Samuel, formerly Lord Mayor of London. This company, which formerly traded almost entirely in Russian oil, undertook a few years ago to develop the oil fields in Borneo, and they built up a large Oriental trade. They soon came into hot competition with the Royal Dutch Company, handling Sumatra oil, and a war of prices ensued which lasted nearly two years. In 1903, however, the two competitors, in connection with four other strong Sumatra and European companies, drew up an agreement in regard to markets which has put an end to their war. The "Shell" people have not only these allies, but they have a contract with the Guffey Petroleum Company, the largest Texas producing concern, to handle its output, and they have gone into a German oil company, the Petroleum Produkten Aktien Gesellschaft. Having thus provided themselves with a supply they have begun developing a European trade on the same lines as their Oriental trade, and they are making serious inroads on the Standard's market.

The naphthas made from the Borneo oil have largely taken the place of American naphtha in many parts of Europe. One load of Borneo benzine even made its appearance in the American market in 1904. It is a sign of what well may happen in the future with an intelligent development of these Russian and Oriental oils—the Standard's domestic market invaded. It will be interesting to see to what further extent the American government will protect the Standard Oil Company by tariff on foreign oils if such a time does come. It has done very well already. The aggressive marketing of the "Shell" and its allies in Europe has led to a recent Oil War of great magnitude. For several months in 1904 American export oil was sold at a lower price in New York than the crude oil it takes to make it costs there. For instance, on August 13, 1904, the New York export price was 4.80 cents per gallon for Standard-white in bulk. Crude sold at the well for $1.50 a barrel of forty-two gallons, and if costs sixty cents to get it to seaboard by pipe-line; that is, forty-two gallons of crude oil costs $2.10, or five cents a gallon in New York—twenty points loss on a gallon of the raw material! But this low price for export affects the local market little or none. The tank-wagon price keeps up to ten and eleven cents in New York. Of course crude is depressed as much as possible to help carry this competition. For many months now there has been the abnormal situation of a declining crude price in face of declining stocks. The truth is the Standard Oil Company is trying to meet the competition of the low-grade Oriental and Russian oils with high-grade American oil—the crude being kept as low as possible, and the domestic market being made to pay for the foreign cutting. It seems a lack of foresight surprising in the Standard to have allowed itself to be found in such a dilemma. Certainly, for over two years the company has been making every effort to escape by getting hold of a supply of low-grade oil which would enable it to meet the competition of the foreigner. There have been more or less short-lived arrangements in Russia. An oil territory in Galicia was secured not long ago by them, and an expert refiner with a full refining plant was sent over. Various hindrances have been met in the undertaking, and the works are not yet in operation. Two years ago the Standard attempted to get hold of the rich Burma oil fields. The press of India fought them out of the country, and their weapon was the Standard Oil Company's own record for hard dealings! The Burma fields are in the hands of a monopoly of the closest sort which has never properly developed the territory, but the people and government prefer their own monopoly to one of the American type!

Altogether the most important question concerning the Standard Oil Company to-day is how far it is sustaining its power by the employment of the peculiar methods of the South Improvement Company. It should never be forgotten that Mr. Rockefeller never depended on these methods alone for securing power in the oil trade. From the beginning the Standard Oil Company has studied thoroughly everything connected with the oil business. It has known, not guessed at conditions. It has had a keen authoritative sight. It has applied itself to its tasks with indefatigable zeal. It has been as courageous as it has been cautious. Nothing has been too big to undertake, as nothing has been too small to neglect. These facts have been repeatedly pointed out in this narrative. But these are the American industrial qualities. They are common enough in all sorts of business. They have made our railroads, built up our great department stores, opened our mines. The Standard Oil Company has no monopoly in business ability. It is the thing for which American men are distinguished to-day in the world.

These qualities alone would have made a great business, and unquestionably it would have been along the line of combination, for when Mr. Rockefeller undertook to work out the good of the oil business the tendency to combination was marked throughout the industry, but it would not have been the combination whose history we have traced. To the help of these qualities Mr. Rockefeller proposed to bring the peculiar aids of the South Improvement Company. He secured an alliance with the railroads to drive out rivals. For fifteen years he received rebates of varying amounts on at least the greater part of his shipments, and for at least a portion of that time he collected drawbacks of the oil other people shipped; at the same time he worked with the railroads to prevent other people getting oil to manufacture, or if they got it he worked with the railroads to prevent the shipment of the product. If it reached a dealer, he did his utmost to bully or wheedle him to countermand his order. If he failed in that, he undersold until the dealer, losing on his purchase, was glad enough to buy thereafter of Mr. Rockefeller. How much of this system remains in force to-day? The spying on independent shipments, the effort to have orders countermanded, the predatory competition prevailing, are well enough known. Contemporaneous documents, showing how these practices have been worked into a very perfect and practically universal system, have already been printed in this work.[13] As for the rebates and drawbacks, if they do not exist in the forms practised up to 1887, as the Standard officials have repeatedly declared, it is not saying that the Standard enjoys no special transportation privileges. As has been pointed out, it controls the great pipe-line handling all but perhaps ten per cent. of the oil produced in the Eastern fields. This system is fully 35,000 miles long. It goes to the wells of every producer, gathers his oil into its storage tanks, and from there transports it to Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, Chicago, Buffalo, Cleveland, or any other refining point where it is needed. This pipe-line is a common carrier by virtue of its use of the right of eminent domain, and, as a common carrier, is theoretically obliged to carry and deliver the oil of all comers, but in practice this does not always work. It has happened more than once in the history of the Standard pipes that they have refused to gather or deliver oil. Pipes have been taken up from wells belonging to individuals running or working with independent refiners. Oil has been refused delivery at points practical for independent refiners. For many years the supply of oil has been so great that the Standard could not refuse oil to the independent refiner on the ground of scarcity. However, a shortage in Pennsylvania oil occurred in 1903. A very interesting situation arose as a result. There are in Ohio and Pennsylvania several independent refiners who, for a number of years, have depended on the Standard lines (the National Transit Company) for their supply of crude. In the fall of 1903 these refiners were informed that thereafter the Standard could furnish them with only fifty per cent. of their refining capacity. It was a serious matter to the independents, who had their own markets, and some of whom were increasing their plants. Supposing we buy oil directly from the producers, they asked one another, must not the Standard as a common carrier gather and deliver it? The experienced in the business said: "Yes. But what will happen? The producer rash enough to sell you oil may be cut off by the National Transit Company. Of course, if he wants to fight in the courts he may eventually force the Standard to reconnect, but they could delay the suit until he was ruined. Also, if you go over Mr. Seep's head"—Mr. Seep is the Standard Oil buyer, and all oil going into the National Transit system goes through his hands—"you will antagonise him." Now, "antagonise" in Standard circles may mean a variety of things. The independent refiners decided to compromise, and an agreement terminable by either party at short notice was made between them and the Standard, by which the members of the former were each to have eighty per cent. of their capacity of crude oil, and were to give to the Standard all of their export oil to market. As a matter of fact, the Standard's ability to cut off crude supplies from the outside refiners is much greater than in the days before the Interstate Commerce Bill, when it depended on its alliance with the railroads to prevent its rival getting oil. It goes without saying that this is an absurd power to allow in the hands of any manufacturer of a great necessity of life. It is exactly as if one corporation aiming at manufacturing all the flour of the country owned all but ten per cent. of the entire railroad system collecting and transporting wheat. They could, of course, in time of shortage, prevent any would-be competitor from getting grain to grind, and they could and would make it difficult and expensive at all times for him to get it.

It is not only in the power of the Standard to cut off outsiders from it, it is able to keep up transportation prices. Mr. Rockefeller owns the pipe system—a common carrier—and the refineries of the Standard Oil Company pay in the final accounting cost for transporting their oil, while outsiders pay just what they paid twenty-five years ago. There are lawyers who believe that if this condition were tested in the courts, the National Transit Company would be obliged to give the same rates to others as the Standard refineries ultimately pay. It would be interesting to see the attempt made.

Not only are outside refiners at just as great disadvantage in securing crude supply to-day as before the Interstate Commerce Commission was formed; they still suffer severe discrimination on the railroads in marketing their product. There are many ways of doing things. What but discrimination is the situation which exists in the comparative rates for oil freight between Chicago and New Orleans, and Cleveland and New Orleans? All, or nearly all, of the refined oil sold by the Standard Oil Company through the Mississippi Valley and the West is manufactured at Whiting, Indiana, close to Chicago, and is shipped on Chicago rates. There are no important independent oil works at Chicago. Now at Cleveland, Ohio, there are independent refiners and jobbers contending for the market of the Mississippi Valley. See how prettily it is managed. The rates between the two Northern cities and New Orleans in the case of nearly all commodities is about two cents per hundred pounds in favour of Chicago. For example, the rate on flour from Chicago is 23 cents per 100 pounds; from Cleveland, 25 cents per 100 pounds; on canned goods the rates are 33 and 35; on lumber, 31 and 33; on meats, 51 and 54; on all sorts of iron and steel, 26 and 29; but on petroleum and its products they are 23 and 33!

In the case of Atlanta, Georgia, a similar vagary of rates exists. Thus Cleveland has, as a rule, about two cents advantage per 100 pounds over Chicago. Flour is shipped from Chicago to Atlanta at 34 cents, and from Cleveland at 32½; lumber at 32 and 28½; but Cleveland refiners actually pay 48 cents to Atlanta, while the Standard only pays 45 from Whiting.

There is a curious rule in the Boston and Maine Railroad in regard to petroleum shipments. On all commodities except petroleum, what is known as the Boston rate applies, but oil does not get this. For instance, the Boston rate applies to Salem, Massachusetts, on all traffic except petroleum, and that pays four cents more per 100 pounds to Salem than to Boston.

The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad gives no through rates on petroleum from Western points, although it gives them on every other commodity. It does not refuse to take oil, but it charges the Boston rate plus the local rates. Thus, to use an illustration given by Mr. Prouty, of the Interstate Commerce Commission, in a recent article, if a Cleveland refiner sends into the New Haven territory, say to New Haven, a car-load of oil, he pays 24 cents per 100 pounds to Boston and the local rate of 12 cents from Boston to New Haven. On any other commodity he would pay the Boston rate. Besides, the rates on petroleum have been materially advanced over what they were when the Interstate Commerce Bill was passed in 1887, although on other commodities they have fallen. In 1887 grain was shipped from Cleveland to Boston for 22 cents, iron for 22, petroleum for 22. In 1889 the rate on grain was 15 cents, on iron 20 cents, and on petroleum 24. Of course it may be merely a coincidence that the New Haven territory can be supplied by the Standard Oil Company from its New York refineries by barge, and that William Rockefeller is a director of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad.

An independent refiner of Titusville, Pennsylvania, T. B. Westgate, told the Industrial Commission in 1898 that his concern was barred from shipping their products to nearly all New England and Canadian points by the refusal of the roads to give the same advantages in tariff which other freight was allowed. Mr. Westgate made the suggestive comment that very few railroads ever solicited oil trade. He pointed out that when the United States Pipe Line was building, agents of various roads were after the oil men soliciting shipments of the pipe, etc., to be used. "We could ship iron, but the oil—we must not handle. That is probably the password that goes over."

Examples of this manipulation might be multiplied. There is no independent refiner or jobber who tries to ship oil freight that does not meet incessant discouragement and discrimination. Not only are rates made to favour the Standard refining points and to protect their markets, but switching charges and dock charges are multiplied. Loading and unloading facilities are refused, payment of freights on small quantities are demanded in advance, a score of different ways are found to make hard the way of the outsider. "If I get a barrel of oil out of Buffalo," an independent dealer told the writer not long ago, "I have to sneak it out. There are no public docks; the railroads control most of them, and they won't let me out if they can help it. If I want to ship a car-load they won't take it if they can help it. They are all afraid of offending the Standard Oil Company."

This may be a rather sweeping statement, but there is too much truth in it. There is no doubt that to-day, as before the Interstate Commerce Commission, a community of interests exists between railroads and the Standard Oil Company sufficiently strong for the latter to get any help it wants in making it hard for rivals to do business. The Standard owns stock in most of the great systems. It is represented on the board of directors of nearly all the great systems, and it has an immense freight not only in oil products, but in timber, iron, acids, and all of the necessities of its factories. It is allied with many other industries, iron, steel, and copper, and can swing freight away from a road which does not oblige it. It has great influence in the money market and can help or hinder a road in securing money. It has great influence in the stock market and can depress or inflate a stock if it sets about it. Little wonder that the railroads, being what they are, are afraid to "disturb their relations with the Standard Oil Company," or that they keep alive a system of discriminations the same in effect as those which existed before 1887.

Of course such cases as those cited above are fit for the Interstate Commerce Commission, but the oil men as a body have no faith in the effectiveness of an appeal to the Commission, and in this feeling they do not reflect on the Commission, but rather on the ignorance and timidity of the Congress which, after creating a body which the people demanded, made it helpless. The case on which the Oil Regions rests its reason for its opinion has already been referred to in the chapter on the co-operative independent movement which finally resulted in the Pure Oil Company. The case first came before the Commission in 1888. At that time there was a small group of independent refiners in Oil City and Titusville, who were the direct outgrowth of the compromise of 1880 between the Producers' Protective Association and the Pennsylvania Railroad. The railroad, having promised open rates to all, urged the men to go into business. Soon after came the great fight between the railroads and the seaboard pipe-line, with the consequent low rates. This warfare finally ended in 1884, after the Standard had brought the Tidewater into line, in a pooling arrangement between the Standard, now controlling all seaboard pipe-lines, and the Pennsylvania Railroad, by which the latter was guaranteed twenty-six per cent. of all Eastern oil shipments on condition that they keep up the rate to the seaboard to fifty-two cents a barrel.

Now, most of the independents shipped by barrels loaded on rack cars. The Standard shipped almost entirely by tank-cars. The custom had always been in the Oil Regions to charge the same for shipments whether by tank or barrel. Suddenly, in 1888, the rate of fifty- two cents on oil in barrels was raised to one of sixty-six cents. The independents believed that the raise was a manipulation of the Standard intended to kill their export trade, and they appealed to the Commission. They pointed out that the railroads and the pipe-lines had been keeping up rates for a long time by a pooling arrangement, and that now the roads made an unreasonable tariff on oil in barrels, at the same time refusing them tank cars. The hearing took place in Titusville in May, 1889. The railroads argued that they had advanced the rate on barrelled oil because of a decision of the Commission itself—a case of very evident discrimination in favour of barrels. The Commission, however, argued that each case brought before it must stand on its own merits, so different were conditions and practices, and in December, 1892, it gave its decision. The pooling arrangement it did not touch, on the ground that the Commission had authority only over railroads in competition, not over railroads and pipe-lines in competition. The chief complaint, that the new rate of sixty-six cents on oil in barrels and not on oil in tanks was an injurious discrimination, the Commission found justified. It ordered that the railroads make the rates the same on oil in both tanks and barrels, and that they furnish shippers tanks whenever reasonable notice was given. As the amounts wrongfully collected by the railroads from the refiners could not be ascertained from the evidence already taken, the Commission decided to hold another hearing and fix the amounts. This was not done until May, 1894, five years after the first hearing. Reparation was ordered to at least eleven different firms, some of the sums amounting to several thousand dollars; the entire award ordered amounted to nearly $100,000.

In case the railroads failed to adjust the claims the refiners were ordered to proceed to enforce them in the courts. The Commission found at this hearing that none of their orders of 1892 had been followed by the roads and they were all repeated. As was to be expected, the roads refused to recognise the claims allowed by the Commission, and the case was taken by the refiners into court. It has been heard three times. Twice they have won, but each time an appeal of the roads has forced them to appear again. The case was last heard at Philadelphia in February, 1904, in the United States Circuit Court of Appeals. No decision had been rendered at this writing.

It would be impossible to offer direct and conclusive proof that the Standard Oil Company persuaded or forced the roads to the change of policy complained of in this case, but the presence of their leading officials and counsel at the hearings, the number of witnesses furnished from their employ, the statement of President Roberts of the Pennsylvania Railroad that the raise on barrelled oil was insisted on by the seaboard refiners (the Standard was then practically the only seaboard refiner) , as well as the perfectly well-known relations of the railroad and the Standard, left no doubt in the minds of those who knew the situation that the order originated with them, and that its sole purpose was harassing their competitors. The Commission seems to have had no doubt of this. But see the helplessness of the Commission. It takes full testimony in 1889, digests it carefully, gives its orders in 1892, and they are not obeyed. More hearings follow, and in 1895 the orders are repeated and reparation is allowed to the injured refiners. From that time to this the case passes from court to court, the railroad seeking to escape the Commission's orders. The Interstate Commerce Commission was instituted to facilitate justice in this matter of transportation, and yet here we have still unsettled a case on which they gave their judgment twelve years ago. The lawyer who took the first appeal to the Commission, that of Rice, Robinson and Winthrop, of Titusville, M. J. Heywang, of Titusville, has been continually engaged in the case for sixteen years!

In spite of the Interstate Commerce Commission, the crucial question is still a transportation question. Until the people of the United States have solved the question of free and equal transportation it is idle to suppose that they will not have a trust question. So long as it is possible for a company to own the exclusive carrier on which a great natural product depends for transportation, and to use this carrier to limit a competitor's supply or to cut off that supply entirely if the rival is offensive, and always to make him pay a higher rate than it costs the owner, it is ignorance and folly to talk about constitutional amendments limiting trusts. So long as the great manufacturing centres of a monopolistic trust can get better rates than the centres of independent effort, it is idle to talk about laws making it a crime to undersell for the purpose of driving a competitor from a market. You must get into markets before you can compete. So long as railroads can be persuaded to interfere with independent pipe-lines, to refuse oil freight, to refuse loading facilities, lest they disturb their relations with the Standard Oil Company, it is idle to talk about investigations or anti-trust legislation or application of the Sherman law. So long as the Standard Oil Company can control transportation as it does to-day, it will remain master of the oil industry, and the people of the United States will pay for their indifference and folly in regard to transportation a good sound tax on oil, and they will yearly see an increasing concentration of natural resources and transportation systems in the Standard Oil crowd.

If all the country had suffered from these raids on competition, had been the limiting of the business opportunity of a few hundred men and a constant higher price for refined oil, the case would be serious enough, but there is a more serious side to it. The ethical cost of all this is the deep concern. We are a commercial people. We cannot boast of our arts, our crafts, our cultivation; our boast is in the wealth we produce. As a consequence business success is sanctified, and, practically, any methods which achieve it are justified by a larger and larger class. All sorts of subterfuges and sophistries and slurring over of facts are employed to explain aggregations of capital whose determining factor has been like that of the Standard Oil Company, special privileges obtained by persistent secret effort in opposition to the spirit of the law, the efforts of legislators, and the most outspoken public opinion. How often does one hear it argued, the Standard Oil Company is simply an inevitable result of economic conditions; that is, given the practices of the oil-bearing railroads in 1872 and the elements of speculation and the over-refining in the oil business, there was nothing for Mr. Rockefeller to do but secure special privileges if he wished to save his business.

Now in 1872 Mr. Rockefeller owned a successful refinery in Cleveland. He had the advantage of water transportation a part of the year, access to two great trunk lines the year around. Under such able management as he could give it his concern was bound to go on, given the demand for refined oil. It was bound to draw other firms to it. When he went into the South Improvement Company it was not to save his own business, but to destroy others. When he worked so persistently to secure rebates after the breaking up of the South Improvement Company, it was in the face of an industry united against them. It was not to save his business that he compelled the Empire Transportation Company to go out of the oil business in 1877. Nothing but grave mismanagement could have destroyed his business at that moment; it was to get every refinery in the country but his own out of the way. It was not the necessity to save his business which compelled Mr. Rockefeller to make war on the Tidewater. He and the Tidewater could both have lived. It was to prevent prices of transportation and of refined oil going down under competition. What necessity was there for Mr. Rockefeller trying to prevent the United States Pipe Line doing business?—only the greed of power and money. Every great campaign against rival interests which the Standard Oil Company has carried on has been inaugurated, not to save its life, but to build up and sustain a monopoly in the oil industry. These are not mere affirmations of a hostile critic; they are facts proved by documents and figures.

Certain defenders go further and say that if some such combination had not been formed the oil industry would have failed for lack of brains and capital. Such a statement is puerile. Here was an industry for whose output the whole world was crying. Petroleum came at the moment when the value and necessity of a new, cheap light was recognised everywhere. Before Mr. Rockefeller had ventured outside of Cleveland kerosene was going in quantities to every civilised country. Nothing could stop it, nothing check it, but the discovery of some cheaper light or the putting up of its price. The real "good of the oil business" in 1872 lay in making oil cheaper. It would flow all over the world on its own merit if cheap enough.

The claim that only by some such aggregation as Mr. Rockefeller formed could enough capital have been obtained to develop the business falls utterly in face of fact. Look at the enormous amounts of capital, a large amount of it speculative, to be sure, which the oil men claim went into their business in the first ten years. It was estimated that Philadelphia alone put over $168,000,000 into the development of the Oil Regions, and New York $134,000,000, in their first decade of the business. How this estimate was reached the authority for it does not say.[14] It may have been the total capitalisation of the various oil companies launched in the two cities in that period. It shows very well, however, in what sort of figures the oil men were dealing. When the South Improvement Company trouble came in 1872, the producers launched a statement in regard to the condition of their business in which they claimed that they were using a capital of $200,000,000. Figures based on the number of oil wells in operation or drilling at that time of course represent only a portion of the capital in use. Wildcatting and speculation have always demanded a large amount of the money that the oil men handled. The almost conservative figures in regard to the capital invested in the Oil Regions in the early years were those of H. E. Wrigley, of the Geological Survey of Pennsylvania. Mr. Wrigley estimates that in the first twelve years of the business $235,000,000 was received from wells. This includes the cost of the land, of putting down and operating the well, also the profit on the product. This estimate, however, makes no allowance for the sums used in speculation—an estimate, indeed, which it was impossible for one to make with any accuracy. The figures, unsatisfactory as they are, are ample proof, however, that there was plenty of money in the early days to carry on the oil business. Indeed, there has always been plenty of money for oil investment. It did not require Mr. Rockefeller's capital to develop the Bradford oil fields, build the first seaboard pipe-line, open West Virginia, Texas, or Kansas. The oil business would no more have suffered for lack of capital without the Standard combination than the iron or wheat or railroad or cotton business. The claim is idle, given the wealth and energy of the country in the forty-five years since the discovery of oil.

Equally well does both the history and the present condition of the oil business show that it has not needed any such aggregation to give us cheap oil. The margin between crude and refined was made low by competition. It has rarely been as low as it would have been had there been free competition. For five years even the small independent refineries outside of the Pure Oil Company have been able to make a profit on the prices set by the Standard, and this in spite of the higher transportation they have paid on both crude and refined, and the wall of seclusion the railroads build around domestic markets.

Very often people who admit the facts, who are willing to see that Mr. Rockefeller has employed force and fraud to secure his ends, justify him by declaring, "It's business." That is, "it's business" has to come to be a legitimate excuse for hard dealing, sly tricks, special privileges. It is a common enough thing to hear men arguing that the ordinary laws of morality do not apply in business. Now, if the Standard Oil Company were the only concern in the country guilty of the practices which have given it monopolistic power, this story never would have been written. Were it alone in these methods, public scorn would long ago have made short work of the Standard Oil Company. But it is simply the most conspicuous type of what can be done by these practices. The methods it employs with such acumen, persistency, and secrecy are employed by all sorts of business men, from corner grocers up to bankers. If exposed, they are excused on the ground that this is business. If the point is pushed, frequently the defender of the practice falls back on the Christian doctrine of charity, and points that we are erring mortals and must allow for each other's weaknesses!—an excuse which, if carried to its legitimate conclusion, would leave our business men weeping on one another's shoulders over human frailty, while they picked one another's pockets.

One of the most depressing features of the ethical side of the matter is that instead of such methods arousing contempt they are more or less openly admired. And this is logical. Canonise "business success," and men who make a success like that of the Standard Oil Trust become national heroes! The history of its organisation is studied as a practical lesson in money-making. It is the most startling feature of the case to one who would like to feel that it is possible to be a commercial people and yet a race of gentlemen. Of course such practices exclude men by all the codes from the rank of gentlemen, just as such practices would exclude men from the sporting world or athletic field. There is no gaming table in the world where loaded dice are tolerated, no athletic field where men must not start fair. Yet Mr. Rockefeller has systematically played with loaded dice, and it is doubtful if there has ever been a time since 1872 when he has run a race with a competitor and started fair. Business played in this way loses all its sportsmanlike qualities. It is fit only for tricksters.

The effects on the very men who fight these methods on the ground that they are ethically wrong are deplorable. Brought into competition with the trust, badgered, foiled, spied upon, they come to feel as if anything is fair when the Standard is the opponent. The bitterness against the Standard Oil Company in many parts of Pennsylvania and Ohio is such that a verdict from a jury on the merits of the evidence is almost impossible! A case in point occurred a few years ago in the Bradford field. An oil producer was discovered stealing oil from the National Transit Company. He had tapped the main line and for at least two years had run a small but steady stream of Standard oil into his private tank. Finally the thieving pipe was discovered, and the owner of it, after acknowledging his guilt, was brought to trial. The jury gave a verdict of Not guilty! They seemed to feel that though the guilt was acknowledged, there probably was a Standard trick concealed somewhere. Anyway it was the Standard Oil Company and it deserved to be stolen from! The writer has frequently heard men, whose own business was conducted with scrupulous fairness, say in cases of similar stealing that they would never condemn a man who stole from the Standard! Of course such a state of feeling undermines the whole moral nature of a community.

The blackmailing cases of which the Standard Oil Company complain are a natural result of its own practices. Men going into an independent refining business have for years been accustomed to say: "Well, if they won't let us alone, we'll make them pay a good price." The Standard complains that such men build simply to sell out. There may be cases of this. Probably there are, though the writer has no absolute proof of any such. Certainly there is no satisfactory proof that the refinery in the famous Buffalo case was built to sell, though that it was offered for sale when the opposition of the Everests, the managers of the Standard concern, had become so serious as later to be stamped as criminal by judge and jury, there is no doubt. Certainly nothing was shown to have been done or said by Mr. Matthews, the owner of the concern which the Standard was fighting, which might not have been expected from a man who had met the kind of opposition he had from the time he went into business.

The truth is, blackmail and every other business vice is the natural result of the peculiar business practices of the Standard. If business is to be treated as warfare and not as a peaceful pursuit, as they have persisted in treating it, they cannot expect the men they are fighting to lie down and die without a struggle. If they get special privileges they must expect their competitors to struggle to get them. If they will find it more profitable to buy out a refinery than to let it live, they must expect the owner to get an extortionate price if he can. And when they complain of these practices and call them blackmail, they show thin sporting blood. They must not expect to monopolise hard dealings, if they do oil.

These are considerations of the ethical effect of such business practices on those outside and in competition. As for those within the organisation there is one obvious effect worth noting. The Standard men as a body have nothing to do with public affairs, except as it is necessary to manipulate them for the "good of the oil business." The notion that the business man must not appear in politics and religion save as a "stand-patter"—not even as a thinking, aggressive force—is demoralising, intellectually and morally. Ever since 1872 the organisation has appeared in politics only to oppose legislation obviously for the public good. At that time the oil industry was young, only twelve years old, and it was suffering from too rapid growth, from speculation, from rapacity of railroads, but it was struggling manfully with all these questions. The question of railroad discriminations and extortions was one of the "live questions" of the country. The oil men as a mass were allied against it. The theory that the railroad was a public servant bound by the spirit of its charter to treat all shippers alike, that fair play demanded open equal rates to all, was generally held in the oil country at the time Mr. Rockefeller and his friends sprung the South Improvement Company. One has only to read the oil journals at the time of the Oil War of 1872 to see how seriously all phases of the transportation question were considered. The country was a unit against the rebate system. Agreements were signed with the railroads that all rates henceforth should be equal. The signatures were not on before Mr. Rockefeller had a rebate, and gradually others got them until the Standard had won the advantages it expected the South Improvement Company to give it. From that time to this Mr. Rockefeller has had to fight the best sentiment of the oil country and of the country at large as to what is for the public good. He and his colleagues kept a strong alliance in Washington fighting the Interstate Commerce Bill from the time the first one was introduced in 1876 until the final passage in 1887. Every measure looking to the freedom and equalisation of transportation has met his opposition, as have bills for giving greater publicity to the operations of corporations. In many of the great state Legislatures one of the first persons to be pointed out to a visitor is the Standard Oil lobbyist. Now, no one can dispute the right of the Standard Oil Company to express its opinions on proposed legislation. It has the same right to do this as all the rest of the world. It is only the character of its opposition which is open to criticism, the fact that it is always fighting measures which equalise privileges and which make it more necessary for men to start fair and play fair in doing business.

Of course the effect of directly practising many of their methods is obvious. For example, take the whole system of keeping track of independent business. There are practices required which corrupt every man who has a hand in them. One of the most deplorable things about it is that most of the work is done by youngsters. The freight clerk who reports the independent oil shipments for a fee of five or ten dollars a month is probably a young man, learning his first lessons in corporate morality. If he happens to sit in Mr. Rockefeller's church on Sundays, through what sort of a haze will he receive the teachings? There is something alarming to those who believe that commerce should be a peaceful pursuit, and who believe that the moral law holds good throughout the entire range of human relations, in knowing that so large a body of young men in this country are consciously or unconsciously growing up with the idea that business is war and that morals have nothing to do with its practice.

And what are we going to do about it? for it is our business. We, the people of the United States, and nobody else, must cure whatever is wrong in the industrial situation, typified by this narrative of the growth of the Standard Oil Company. That our first task is to secure free and equal transportation privileges by rail, pipe and waterway is evident. It is not an easy matter. It is one which may require operations which will seem severe; but the whole system of discrimination has been nothing but violence, and those who have profited by it cannot complain if the curing of the evils they have wrought bring hardship in turn on them. At all events, until the transportation matter is settled, and settled right, the monopolistic trust will be with us, a leech on our pockets, a barrier to our free efforts.

As for the ethical side, there is no cure but in an increasing scorn of unfair play—an increasing sense that a thing won by breaking the rules of the game is not worth the winning. When the business man who fights to secure special privileges, to crowd his competitor off the track by other than fair competitive methods, receives the same summary disdainful ostracism by his fellows that the doctor or lawyer who is "unprofessional," the athlete who abuses the rules, receives, we shall have gone a long way toward making commerce a fit pursuit for our young men.

THE END

- ↑ Ohio Circuit Court Reports, Volume VII, 1893, page 508.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 60. Facsimile of one of Mr. Kemper's shares.

- ↑ History of Standard Oil Case in Supreme Court of Ohio, 1897-1898. Part II, page 39.

- ↑ History of Standard Oil Case in Supreme Court of Ohio, 1897-1898. Part II, page 248.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 53.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 61. General balance sheet, Standard Oil interests, December 31, 1896.

- ↑ The present directors are John D. Rockefeller, William Rockefeller, Henry M. Flagler, John D. Archbold, Henry H. Rogers, W. H. Tilford, Frank Q. Barstow, Charles M. Pratt, E. T. Bedford, Walter Jennings, James A. Moffett, C. W. Harkness, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Oliver H. Payne.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 62. Amended certificate of incorporation of the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 9.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 63. Production of Pennsylvania and Lima crude oil by Standard Oil Company, 1890-1898.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 64. Business of Standard Oil Company and other refiners, 1894-1898.

- ↑ America imported into China, 1893, 31,060,527 gallons. Borneo imported into China, 1893, 574,615 gallons. Russia imported into China, 1893, 13,503,685 gallons. Sumatra imported into China, 1893, 39,859,508 gallons.

- ↑ See Chapter X.

- ↑ The Petroleum Age, Volume I, page 35.