Minneapolis was an example of police corruption; St. Louis of financial corruption. Pittsburg is an example of both police and financial corruption. The two other cities have found each an official who has exposed them. Pittsburg has had no such man and no exposure. The city has been described physically as “Hell with the lid off”; politically it is hell with the lid on. I am not going to lift the lid. The exposition of what the people know and stand is the purpose of these articles, not the exposure of corruption, and the exposure of Pittsburg is not necessary. There are earnest men in the town who declare it must blow up of itself soon. I doubt that; but even if it does burst, the people of Pittsburg will learn little more than they know now. It is not ignorance that keeps American citizens subservient; neither is it indifference. The Pittsburgers know, and a strong minority of them care; they have risen against their ring and beaten it, only to look about and find another ring around them. Angry and ashamed, Pittsburg is a type of the city that has tried to be free and failed.

A sturdy city it is, too, the second in Pennsylvania. Two rivers flow past it to make a third, the Ohio, in front, and all around and beneath it are natural gas and coal which feed a thousand furnaces that smoke all day and flame all night to make Pittsburg the Birmingham of America. Rich in natural resources, it is richest in the quality of its population. Six days and six nights these people labor, molding iron and forging steel, and they are not tired; on the seventh day they rest, because that is the Sabbath. They are Scotch Presbyterians and Protestant Irish. This stock had an actual majority not many years ago, and now, though the population has grown to 354,000 in Pittsburg proper (counting Allegheny across the river, 130,000, and other communities, politically separate, but essentially integral parts of the proposed Greater Pittsburg, the total is 750,000), the Scotch and Scotch-Irish still predominate, and their clean, strong faces characterize the crowds in the streets. Canny, busy, and brave, they built up their city almost in secret, making millions and hardly mentioning it. Not till outsiders came in to buy some of them out did the world (and Pittsburg and some of the millionaires in it) discover that the Iron City had been making not only steel and glass, but multimillionaires. A banker told a business man as a secret one day about three years ago that within six months a “bunch of about a hundred new millionaires would be born in Pittsburg,” and the births happened on time. And more beside. But even the bloom of millions did not hurt the city. Pittsburg is an unpretentious, prosperous city of tremendous industry and healthy, steady men.

Superior as it is in some other respects, however, Scotch-Irish Pittsburg, politically, is no better than Irish New York or Scandinavian Minneapolis, and little better than German St. Louis. These people, like any other strain of the free American, have despoiled the government—despoiled it, let it be despoiled, and bowed to the despoiling boss. There is nothing in the un-American excuse that this or that foreign nationality has prostituted “our great and glorious institutions.” We all do it, all breeds alike. And there is nothing in the complaint that the lower elements of our city populations are the source of our disgrace. In St. Louis corruption came from the top, in Minneapolis from the bottom. In Pittsburg it comes from both extremities, but it began above.

The railroads began the corruption of this city. There “always was some dishonesty,” as the oldest public men I talked with said, but it was occasional and criminal till the first great corporation made it business-like and respectable. The municipality issued bonds to help the infant railroads to develop the city, and, as in so many American cities, the roads repudiated the debt and interest, and went into politics. The Pennsylvania Railroad was in the system from the start, and, as the other roads came in and found the city government bought up by those before them, they purchased their rights of way by outbribing the older roads, then joined the ring to acquire more rights for themselves and to keep belated rivals out. As corporations multiplied and capital branched out corruption increased naturally, but the notable characteristic of the “Pittsburg plan” of misgovernment was that it was not a haphazard growth, but a deliberate, intelligent organization. It was conceived in one mind, built up by one will, and this master spirit ruled, not like Croker in New York, a solid majority; nor like Butler in St. Louis, a bi-partisan minority; but the whole town—financial, commercial, and political. The boss of Pittsburg was Christopher L. Magee, a great man, and when he died he was regarded by many of the strongest men in Pittsburg as their leading citizen.

“Chris,” as he was called, was a charming character. I have seen Pittsburgers grow black in the face denouncing his ring, but when I asked, “What kind of a man was Magee?” they would cool and say, “Chris? Chris was one of the best men God ever made.” If I smiled, they would say, “That is all right. You smile, and you can go ahead and show up the ring. You may describe this town as the worst in the country. But you get Magee wrong and you’ll have all Pittsburg up in arms.” Then they would tell me that “Magee robbed the town,” or, perhaps, they would speak of the fund raising to erect a monument to the dead boss.

So I must be careful. And, to begin with, Magee did not, technically speaking, rob the town. That was not his way, and it would be a carelessly unnecessary way in Pennsylvania. But surely he does not deserve a monument.

Magee was an American. His paternal great-grandfather served in the Revolution, and settled in Pittsburg at the close of the war. Christopher was born on Good Friday, April 14, 1848. He was sent to school till he was fifteen years old. Then his father died, and “Squire” or “Tommy” Steele, his uncle, a boss of that day, gave him his start in life with a place in the City Treasury. When just twenty-one, he made him cashier, and two years later Chris had himself elected City Treasurer by a majority of 1,100 on a ticket the head of which was beaten by 1,500 votes.

Such was his popularity; and, though he systematized and capitalized it, it lasted to the end, for the foundation thereof was goodness of heart and personal charm. Magee was tall, strong, and gracefully built. His hair was dark till it turned gray, then his short mustache and his eyebrows held black, and his face expressed easily sure power and genial, hearty kindness. But he was ambitious for power, and all his goodness of heart was directed by a shrewd mind.

When Chris saw the natural following gathering about him he realized, young as he was, the use of it, and he retired from office (holding only a fire commissionership) with the avowed purpose of becoming a boss. Determined to make his ring perfect, he went to Philadelphia to study the plan in operation there. Later, when the Tweed ring was broken, he spent months in New York looking into Tammany’s machine methods and the mistakes which had led to its exposure and disruption. With that cheerful candor which softens indignation he told a fellow-townsman (who told me) what he was doing in New York; and when Magee returned he reported that a ring could be made as safe as a bank. He had, to start with, a growing town too busy for self-government; two not very unequal parties, neither of them well organized; a clear field in his own, the majority party in the city, county, and State. There was boodle, but it was loosely shared by too many persons. The governing instrument was the old charter of 1816, which lodged all the powers—legislative, administrative, and executive—in the councils, common and select. The mayor was a peace officer, with no responsible power. Indeed, there was no responsibility anywhere. There were no departments. Committees of councils did the work usually done by departments, and the councilmen, unsalaried and unanswerable individually, were organized into what might have become a combine had not Magee set about establishing the one-man power there.

To control councils Magee had to organize the wards, and he was managing this successfully at the primaries, when a new and an important figure appeared on the scene—William Flinn. Flinn was Irish, a Protestant of Catholic stock, a boss contractor, and a natural politician. He beat one of Magee’s brothers in his ward. Magee laughed, inquired, and, finding him a man of opposite or complementary disposition and talents, took him into a partnership. A happy, profitable combination, it lasted for life. Magee wanted power, Flinn wealth. Each got both these things; but Magee spent his wealth for more power, and Flinn spent his power for more wealth. Magee was the sower, Flinn the reaper. In dealing with men they came to be necessary to each other, these two. Magee attracted followers, Flinn employed them. The men Magee won Flinn compelled to obey, and those he lost Magee won back. When the councils were first under his control Magee stood in the lobby to direct them, always by suggestions and requests, which sometimes a mean and ungrateful fellow would say he could not heed. Magee told him it was all right, which saved the man, but lost the vote. So Flinn took the lobby post, and he said: “Here, you go and vote aye.” If they disobeyed the plain order Flinn punished them, and so harshly that they would run to Magee to complain. He comforted them. “Never mind Flinn,” he would say sympathetically; “he gives me no end of trouble, too. But I’d like to have you do what he asked. Go and do it for me, and let me attend to Flinn. I’ll fix him.”

Magee could command, too, and fight and punish. If he had been alone he probably would have hardened with years. And so Flinn, after Magee died, softened with time, but too late. He was useful to Magee, Magee was indispensable to him. Molasses and vinegar, diplomacy and force, mind and will, they were well mated. But Magee was the genius. It was Magee that laid the plans they worked out together.

Boss Magee’s idea was not to corrupt the city government, but to be it; not to hire votes in councils, but to own councilmen; and so, having seized control of his organization, he nominated cheap or dependent men for the select and common councils. Relatives and friends were his first recourse, then came bartenders, saloon-keepers, liquor dealers, and others allied to the vices, who were subject to police regulation and dependent in a business way upon the maladministration of law. For the rest he preferred men who had no visible means of support, and to maintain them he used the usual means—patronage. And to make his dependents secure he took over the county government. Pittsburg is in Allegheny County, which has always been more strongly Republican than the city. No matter what happened in the city, the county pay-roll was always Magee’s, and he made the county part of the city government.

With all this city and county patronage at his command, Magee went deliberately about undermining the Democratic party. The minority organization is useful to a majority leader; it saves him trouble and worry in ordinary times; in party crises he can use it to whip his own followers into line; and when the people of a city rise in revolt it is essential for absolute rule that you have the power not only to prevent the minority leaders from combining with the good citizens, but to unite the two organizations to whip the community into shape. Moreover, the existence of a supposed opposition party splits the independent vote and helps to keep alive that sentiment, “loyalty to party,” which is one of the best holds the boss has on his unruly subjects. All bosses, as we have seen in Minneapolis and St. Louis, rise above partisan bias. Magee, the wisest of them, was also the most generous, and he liked to win over opponents who were useful to him. Whenever he heard of an able Democratic worker in a ward, he sent for his own Republican leader. “So-and-so is a good man, isn’t he?” he would ask. “Going to give you a run, isn’t he? Find out what he wants, and we’ll see what we can do. We must have him.” Thus the able Democrat achieved office for himself or his friend, and the city or the county paid. At one time, I was told, nearly one-quarter of the places on the pay-roll were held by Democrats, who were, of course, grateful to Chris Magee, and enabled him in emergencies to wield their influence against revolting Republicans. Many a time a subservient Democrat got Republican votes to beat a “dangerous” Republican, and when Magee, toward the end of his career, wished to go to the State Senate, both parties united in his nomination and elected him unanimously.

Business men came almost as cheap as politicians, and they came also at the city’s expense. Magee had control of public funds and the choice of depositories. That is enough for the average banker—not only for him that is chosen, but for him also that may some day hope to be chosen—and Magee dealt with the best of those in Pittsburg. This service, moreover, not only kept them docile, but gave him and Flinn credit at their banks. Then, too, Flinn and Magee’s operations soon developed on a scale which made their business attractive to the largest financial institutions for the profits on their loans, and thus enabled them to distribute and share in the golden opportunities of big deals. There are ring banks in Pittsburg, ring trust companies, and ring brokers. The manufacturers and the merchants were kept well in hand by many little municipal grants and privileges, such as switches, wharf rights, and street and alley vacations. These street vacations are a tremendous power in most cities. A foundry occupies a block, spreads to the next block, and wants the street between. In St. Louis the business man boodled for his street. In Pittsburg he went to Magee, and I have heard such a man praise Chris, “because when I called on him his outer office was filled with waiting politicians, but he knew I was a business man and in a hurry; he called me in first, and he gave me the street without any fuss. I tell you it was a sad day for Pittsburg when Chris Magee died.” This business man, the typical American merchant everywhere, cares no more for his city’s interest than the politician does, and there is more light on American political corruption in such a speech than in the most sensational exposure of details. The business men of Pittsburg paid for their little favors in “contributions to the campaign fund,” plus the loss of their self-respect, the liberty of the citizens generally, and (this may appeal to their mean souls) in higher taxes.

As for the railroads, they did not have to be bought or driven in; they came, and promptly, too. The Pennsylvania appeared early, just behind Magee, who handled their passes and looked out for their interest in councils and afterwards at the State Legislature. The Pennsylvania passes, especially those to Atlantic City and Harrisburg, have always been a “great graft” in Pittsburg. For the sort of men Magee had to control a pass had a value above the price of a ticket; to “flash” one is to show a badge of power and relationship to the ring. The big ringsters, of course, got from the railroads financial help when cornered in business deals—stock tips, shares in speculative and other financial turns, and political support. The Pennsylvania Railroad is a power in Pennsylvania politics, it is part of the State ring, and part also of the Pittsburg ring. The city paid in all sorts of rights and privileges, streets, bridges, etc., and in certain periods the business interests of the city were sacrificed to leave the Pennsylvania Road in exclusive control of a freight traffic it could not handle alone.

With the city, the county, the Republican and Democratic organizations, the railroads and other corporations, the financiers and the business men, all well under control, Magee needed only the State to make his rule absolute. And he was entitled to it. In a State like New York, where one party controls the Legislature and another the city, the people in the cities may expect some protection from party opposition. In Pennsylvania, where the Republicans have an overwhelming majority, the Legislature at Harrisburg is an essential part of the government of Pennsylvania cities, and that is ruled by a State ring. Magee’s ring was a link in the State ring, and it was no more than right that the State ring should become a link in his ring. The arrangement was easily made. One man, Matthew S. Quay, had received from the people all the power in the State, and Magee saw Quay. They came to an understanding without the least trouble. Flinn was to be in the Senate, Magee in the lobby, and they were to give unto Quay political support for his business in the State in return for his surrender to them of the State’s functions of legislation for the city of Pittsburg.

Now such understandings are common in our politics, but they are verbal usually and pretty well kept, and this of Magee and Quay was also founded in secret good faith. But Quay, in crises, has a way of straining points to win, and there were no limits to Magee’s ambition for power. Quay and Magee quarreled constantly over the division of powers and spoils, so after a few years of squabbling they reduced their agreement to writing. This precious instrument has never been published. But the agreement was broken in a great row once, and when William Flinn and J. O. Brown undertook to settle the differences and renew the bond, Flinn wrote out in pencil in his own hand an amended duplicate which he submitted to Quay, whose son subsequently gave it out for publication. A facsimile of one page is reproduced in this article. Here is the whole contract, with all the unconscious humor of the “party of the first part” and “said party of the second part,” a political-legal-commercial insult to a people boastful of self-government:

“Memorandum and agreement between M. S. Quay of the first part and J. O. Brown and William Flinn of the second part, the consideration of this agreement being the mutual political and business advantage which may result therefrom.

“First—The said M. S. Quay is to have the benefit of the influence in all matters in state and national politics of the said parties of the second part, the said parties agreeing that they will secure the election of delegates to the state and national convention, who will be guided in all matters by the wishes of the said party of the first part, and who will also secure the election of members of the state senate from the Forty-third, Forty-fourth, and Forty-fifth senatorial districts, and also secure the election of members of the house of representatives south of the Monongahela and Ohio rivers in the county of Allegheny, who will be guided by the wishes and request of the said party of the first part during the continuance of this agreement upon all political matters. The different candidates for the various positions mentioned shall be selected by the parties of the second part, and all the positions of state and national appointments made in this territory mentioned shall be satisfactory to and secure the indorsement of the party of the second part, when the appointment is made either by or through the party of the first part, or his friends or political associates. All legislation affecting the parties of the second part, affecting cities of the second class, shall receive the hearty co-operation and assistance of the party of the first part, and legislation which may affect their business shall likewise receive the hearty co-operation and help of the party of the first part. It being distinctly understood that at the approaching national convention, to be held at St. Louis, the delegates from the Twenty-second congressional district shall neither by voice nor vote do other than what is satisfactory to the party of the first part. The party of the first part agrees to use his influence and secure the support of his friends and political associates to support the Republican county and city ticket, when nominated, both in the city of Pittsburg and Allegheny, and the county of Allegheny, and that he will discountenance the factional fighting by his friends and associates for county offices during the continuation of this agreement. This agreement is not to be binding upon the parties of the second part when a candidate for any office who [sic] shall reside in Allegheny county, and shall only be binding if the party of the first part is a candidate for United States senator to succeed himself so far as this office is concerned. In the Forty-third senatorial district a new senator shall be elected to succeed Senator Upperman. In the Forty-fifth senatorial district the party of the first part shall secure the withdrawal of Dr. A. J. Barchfeld, and the parties of the second part shall withdraw as a candidate Senator Steel, and the parties of the second part shall secure the election of some party satisfactory to themselves. In the Twenty-second congressional district the candidates for congress shall be selected by the party of the second part. The term of this agreement to be for —— years from the signing thereof, and shall be binding upon all parties when signed by C. L. Magee.”

Thus was the city of Pittsburg turned over by the State to an individual to do with as he pleased. Magee’s ring was complete. He was the city, Flinn was the councils, the county was theirs, and now they had the State Legislature so far as was concerned. Magee and Flinn were the government and the law. How could they commit a crime? If they wanted something from the city they passed an ordinance granting it, and if some other ordinance was in conflict it was repealed or amended. If the laws in the State stood in the way, so much the worse for the laws of the State; they were amended. If the constitution of the State proved a barrier, as it did to all special legislation, the Legislature enacted a law for cities of the second class (which was Pittsburg alone) and the courts upheld the Legislature. If there were opposition on the side of public opinion, there was a use for that also.

The new charter which David D. Bruce fought through councils in 1886–87 was an example of the way Magee and, after him, Quay and other Pennsylvania bosses employed popular movements. As his machine grew Magee found council committees unwieldy in some respects, and he wanted a change. He took up Bruce’s charter, which centered all executive and administrative power and responsibility in the mayor and heads of departments, passed it through the Legislature, but so amended that the heads of departments were not to be appointed by the mayor, but elected by councils. These elections were by expiring councils, so that the department chiefs held over, and with their patronage insured the re-election of the councilmen who elected them. The Magee-Flinn machine, perfect before, was made self-perpetuating. I know of nothing like it in any other city. Tammany in comparison is a plaything, and in the management of a city Croker was a child beside Chris Magee.

The graft of Pittsburg falls conveniently into four classes: franchises, public contracts, vice, and public funds. There was, besides these, a lot of miscellaneous loot—public supplies, public lighting, and the water supply. You hear of second-class fire-engines taken at first-class prices, water rents from the public works kept up because a private concern that supplied the South Side could charge no more than the city, a gas contract to supply the city lightly availed of. But I cannot go into these. Neither can I stop for the details of the system by which public funds were left at no interest with favored depositories from which the city borrowed at a high rate, or the removal of funds to a bank in which the ringsters were shareholders. All these things were managed well within the law, and that was the great principle underlying the Pittsburg plan.

The vice graft, for example, was not blackmail as it is in New York and most other cities. It is a legitimate business, conducted, not by the police, but in an orderly fashion by syndicates, and the chairman of one of the parties at the last election said it was worth $250,000 a year. I saw a man who was laughed at for offering $17,500 for the slot-machine concession; he was told that it was let for much more. “Speak-easies” (unlicensed drinking places) pay so well that when they earn $500 or more in twenty-four hours their proprietors often make a bare living. Disorderly houses are managed by ward syndicates. Permission is had from the syndicate real estate agent, who alone can rent them. The syndicate hires a house from the owners at, say, $35 a month, and he lets it to a woman at from $35 to $50 a week. For furniture the tenant must go to the “official furniture man,” who delivers $1,000 worth of “fixings” for a note for $3,000, on which high interest must be paid. For beer the tenant must go to the “official bottler,” and pay $2 for a one-dollar case of beer; for wines and liquors to the “official liquor commissioner,” who charges $10 for five dollars’ worth; for clothes to the “official wrapper maker.” These women may not buy shoes, hats, jewelry, or any other luxury or necessity except from the official concessionaries, and then only at the official, monopoly prices. If the victims have anything left, a police or some other city official is said to call and get it (there are rich ex-police officials in Pittsburg). But this is blackmail and outside the system, which is well understood in the community. Many men, in various walks of life, told me separately the names of the official bottlers, jewelers, and furnishers; they are notorious, but they are safe. They do nothing illegal. Oppressive, wretched, what you please, the Pittsburg system is safe.

That was the keynote of the Flinn-Magee plan, but this vice graft was not their business. They are credited with the suppression of disorder and decent superficial regulations of vice, which is a characteristic of Pittsburg. I know it is said that under the Philadelphia and Pittsburg plans, which are much alike, “all graft and all patronage go across one table,” but if any “dirty money” reached the Pittsburg bosses it was, so far as I could prove, in the form of contributions to the party fund, and came from the vice dealers only as it did from other business men.

Magee and Flinn, owners of Pittsburg, made Pittsburg their business, and, monopolists in the technical economic sense of the word, they prepared to exploit it as if it were their private property. For convenience they divided it between them. Magee took the financial and corporate branch, turning the streets to his uses, delivering to himself franchises, and building and running railways. Flinn went in for public contracts for his firm, Booth & Flinn, Limited, and his branch boomed. Old streets were repaved, new ones laid out; whole districts were improved, parks made, and buildings erected. The improvement of their city went on at a great rate for years, with only one period of cessation, and the period of economy was when Magee was building so many traction lines that Booth & Flinn, Ltd., had all they could do with this work. It was said that no other contractors had an adequate “plant” to supplement properly the work of Booth & Flinn, Ltd. Perhaps that was why this firm had to do such a large proportion of the public work always. Flinn’s Director of Public Works was E. M. Bigelow, a cousin of Chris Magee and another nephew of old Squire Steele. Bigelow, called the Extravagant, drew the specifications; he made the awards to the lowest responsible bidders, and he inspected and approved the work while in progress and when done.

Flinn had a quarry, the stone of which was specified for public buildings; he obtained the monopoly of a certain kind of asphalt, and that kind was specified. Nor was this all. If the official contractor had done his work well and at reasonable prices the city would not have suffered directly; but his methods were so oppressive upon property holders that they caused a scandal. No action was taken, however, till Oliver McClintock, a merchant, in rare civic wrath, contested the contracts and fought them through the courts. This single citizen’s long, brave fight is one of the finest stories in the history of municipal government. The frowns and warnings of cowardly fellow-citizens did not move him, nor the boycott of other business men, the threats of the ring, and the ridicule of ring organs. George W. Guthrie joined him later, and though they fought on undaunted, they were beaten again and again. The Director of Public Works controlled the initiative in court proceedings; he chose the judge who appointed the Viewers, with the result, Mr. McClintock reported, that the Department prepared the Viewers’ reports. Knowing no defeat, Mr. McClintock photographed Flinn’s pavements at places where they were torn up to show that “large stones, as they were excavated from sewer trenches, brick bats, and the débris of old coal-tar sidewalks were promiscuously dumped in to make foundations, with the result of an uneven settling of the foundation, and the sunken and worn places so conspicuous everywhere in the pavements of the East End.” One outside asphalt company tried to break the monopoly, but was easily beaten in 1889, withdrew, and after that one of its officers said, “We all gave Pittsburg a wide berth, recognizing the uselessness of offering competition so long as the door of the Department of Public Works is locked against us, and Booth & Flinn are permitted to carry the key.” The monopoly caused not only high prices on short guarantee, but carried with it all the contingent work. Curbing and grading might have been let separately, but they were not. In one contract Mr. McClintock cites, Booth & Flinn bid 50 cents for 44,000 yards of grading. E. H. Bochman offered a bid of 15 cents for the grading as a separate contract, and his bid was rejected. A property-owner on Shady Lane, who was assessed for curbing at 80 cents a foot, contracted privately at the same time for 800 feet of the same standard curbing, from the same quarry, and set in place in the same manner, at 40 cents a foot!

“During the nine years succeeding the adoption of the charter of 1887,” says Mr. Oliver McClintock in a report to the National Municipal League, “one firm [Flinn’s] received practically all the asphalt-paving contracts at prices ranging from $1 to $1.80 per square yard higher than the average price paid in neighboring cities. Out of the entire amount of asphalt pavements laid during these nine years, represented by 193 contracts, and costing $3,551,131, only nine street blocks paved in 1896, and costing $33,400, were not laid by this firm.”

The building of bridges in this city of bridges, the repairing of pavements, park-making, and real estate deals in anticipation of city improvements were all causes of scandal to some citizens, sources of profit to others who were “let in on the ground floor.” There is no space for these here. Another exposure came in 1897 over the contracts for a new Public Safety Building. J. O. Brown was Director of Public Safety. A newspaper, the Leader, called attention to a deal for this work, and George W. Guthrie and William B. Rogers, leading members of the Pittsburg bar, who followed up the subject, discovered as queer a set of specifications for the building itself as any city has on record. Favored contractors were named or their wares described all through, and a letter to the architect from J. O. Brown contained specifications for such favoritism, as, for example: “Specify the Westinghouse electric-light plant and engines straight.” “Describe the Van Horn Iron Co.’s cells as close as possible.” The stone clause was Flinn’s, and that is the one that raised the rumpus. Flinn’s quarry produced Ligonier block, and Ligonier block was specified. There was a letter from Booth & Flinn, Ltd., telling the architect that the price was to be specified at $31,500. A local contractor offered to provide Tennessee granite set up, a more expensive material, on which the freight is higher, at $19,880; but that did not matter. When another local contracting firm, however, offered to furnish Ligonier block set up at $18,000, a change was necessary, and J. O. Brown directed the architect to “specify that the Ligonier block shall be of a bluish tint rather than a gray variety.” Flinn’s quarry had the bluish tint, the other people’s “the gray variety.” It was shown also that Flinn wrote to the architect on June 24, 1895, saying: “I have seen Director Brown and Comptroller Gourley to-day, and they have agreed to let us start on the working plans and get some stone out for the new building. Please arrange that we may get the tracings by Wednesday.…” The tracings were furnished him, and thus before the advertisements for bids were out he began preparing the bluish tint stone. The charges were heard by a packed committee of councils, and nothing came of them; and, besides, they were directed against the Director of Public Works, not William Flinn.

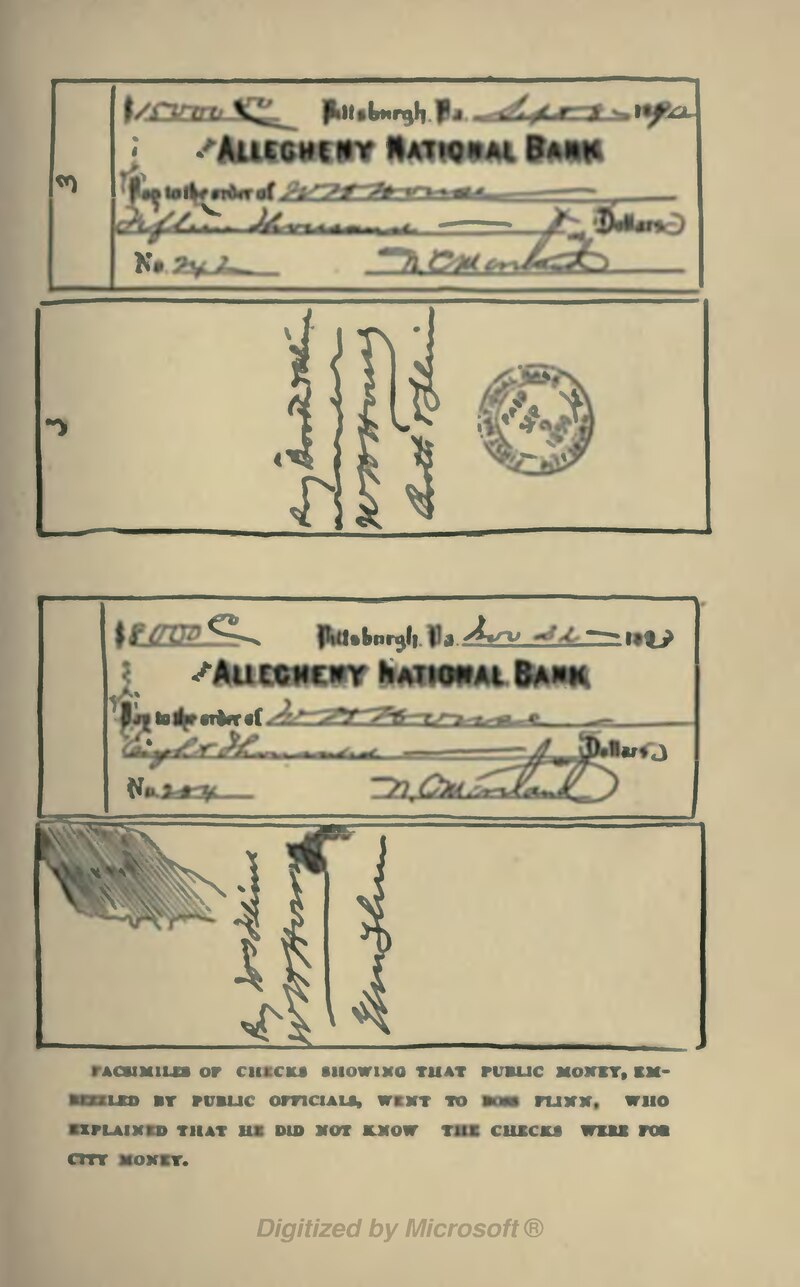

The boss was not an official, and not responsible. The only time Flinn was in danger was on a suit that grew out of the conviction of the City Attorney, W. C. Moreland, and L. H. House, his assistant, for the embezzlement of public funds. These officials were found to be short about $300,000. One of them pleaded guilty, and both went to prison without telling where the money went, and that information did not develop till later. J. B. Connelly, of the Leader, discovered in the City Attorney’s office stubs of checks indicating that some $118,000 of it had gone to Flinn or to Booth & Flinn, Ltd. When Flinn was first asked about it by a reporter he said that the items were correct, that he got them, but that he had explained it all to the Comptroller and had satisfied him. This answer indicated a belief that the money belonged to the city. When he was sued by the city he said that he did not know it was city money. He thought it was personal loans from House. Now House was not a well-to-do man, and his city salary was but $2,500 a year. Moreover, the checks, two of which are reproduced here, are signed by the City Attorney, W. C. Moreland, and are for amounts ranging from five to fifteen thousand dollars. But where was the money? Flinn testified that he had paid it back to House. Then where were the receipts? Flinn said they had been burned in a fire that had occurred in Booth & Flinn’s office. The judge found for Flinn, holding that it had not been proven that Flinn knew the checks were for public money, nor that he had not repaid the amount.

As I have said before, however, unlawful acts were exceptional and unnecessary in Pittsburg. Magee did not steal franchises and sell them. His councils gave them to him. He and the busy Flinn took them, built railways, which Magee sold and bought and financed and conducted, like any other man whose successful career is held up as an example for young men. His railways, combined into the Consolidated Traction Company, were capitalized at $30,000,000. The public debt of Pittsburg is about $18,000,000, and the profit on the railway building of Chris Magee would have wiped out the debt. “But you must remember,” they say in the Pittsburg banks, “that Magee took risks, and his profits are the just reward of enterprise.” This is business. But politically speaking it was an abuse of the powers of a popular ruler for Boss Magee to give to Promoter Magee all the streets he wanted in Pittsburg at his own terms: forever, and nothing to pay. There was scandal in Chicago over the granting of charters for twenty-eight and fifty years. Magee’s read: “for 950 years,” “for 999 years,” “said Charter is to exist a thousand years,” “said Charter is to exist perpetually,” and the councils gave franchises for the “life of the Charter.” There is a legend that Fred Magee, a waggish brother of Chris, put these phrases into these grants for fun, and no doubt the genial Chris saw the fun of it. I asked if the same joker put in the car tax, which is the only compensation the city gets for the use forever of its streets; but it was explained that that was an oversight. The car tax was put upon the old horse-cars, and came down upon the trolley because, having been left unpaid, it was forgotten. This car tax on $30,000,000 of property amounts to less than $15,000 a year, and the companies have until lately been slow about paying it. During the twelve years succeeding 1885 all the traction companies together paid the city $60,000. While the horse vehicles in 1897 paid $47,000, and bicycles $7,000, the Consolidated Traction Company[1] (C. L. Magee, President) paid $9,600. The speed of bicycles and horse vehicles is limited by law, that of the trolley is unregulated. The only requirement of the law upon them is that the traction company shall keep in repair the pavement between and a foot outside of the tracks. This they don’t do, and they make the city furnish twenty policemen as guards for crossings of their lines at a cost of $20,000 a year in wages.

Not content with the gift of the streets, the ring made the city work for the railways. The building of bridges is one function of the municipality as a servant of the traction company. Pittsburg is a city of many bridges, and many of them were built for ordinary traffic. When the Magee railways went over them some of them had to be rebuilt. The company asked the city to do it, and despite the protests of citizens and newspapers, the city rebuilt iron bridges in good condition and of recent construction to accommodate the tracks. Once some citizens applied for a franchise to build a connecting line along what is now part of the Bloomfield route, and by way of compensation offered to build a bridge across the Pennsylvania tracks for free city use, they only to have the right to run their cars on it. They did not get their franchise. Not long after Chris Magee (and Flinn) got it, and they got it for nothing; and the city built this bridge, rebuilt three other bridges over the Pennsylvania tracks, and one over the Junction Railroad—five bridges in all, at a cost of $160,000!

Canny Scots as they were, the Pittsburgers submitted to all this for a quarter of a century, and some $34,000 has been subscribed toward the monument to Chris Magee. This sounds like any other well-broken American city; but to the credit of Pittsburg be it said that there never was a time when some few individuals were not fighting the ring. David D. Bruce was standing for good government way back in the ’fifties. Oliver McClintock and George W. Guthrie we have had glimpses of, struggling, like John Hampden, against their tyrants; but always for mere justice and in the courts, and all in vain, till in 1895 their exposures began to bring forth signs of public feeling, and they ventured to appeal to the voters, the sources of the bosses’ power. They enlisted the venerable Mr. Bruce and a few other brave men, and together called a mass-meeting. A crowd gathered. There were not many prominent men there, but evidently the people were with them, and they then and there formed the Municipal League, and launched it upon a campaign to beat the ring at the February election, 1896.

A committee of five was put in charge—Bruce, McClintock, George K. Stevenson, Dr. Pollock, and Otto Heeren—who combined with Mr. Guthrie’s sterling remnant of the Democratic party on an independent ticket, with Mr. Guthrie at the head for mayor. It was a daring thing to do, and they discovered then what we have discovered in St. Louis and Minneapolis. Mr. Bruce told me that, after their mass-meeting, men who should have come out openly for the movement approached him by stealth and whispered that he could count on them for money if he would keep secret their names. “Outside of those at the meeting,” he said, “but one man of all those that subscribed would let his name appear. And men who gave me information to use against the ring spoke themselves for the ring on the platform.” Mr. McClintock in a paper read before a committee of the National Municipal League says: “By far the most disheartening discovery, however, was that of the apathetic indifference of many representative citizens—men who from every other point of view are deservedly looked upon as model members of society. We found that prominent merchants and contractors who were ‘on the inside,’ manufacturers enjoying special municipal privileges, wealthy capitalists, brokers, and others who were holders of the securities of traction and other corporations, had their mouths stopped, their convictions of duty strangled, and their influence before and votes on election day preempted against us. In still another direction we found that the financial and political support of the great steam railroads and largest manufacturing corporations, controlling as far as they were able the suffrages of their thousands of employees, were thrown against us, for the simple reason, as was frankly explained by one of them, that it was much easier to deal with a boss in promoting their corporate interests than to deal directly with the people’s representatives in the municipal legislature. We even found the directors of many banks in an attitude of cold neutrality, if not of active hostility, toward any movement for municipal reform. As one of them put it, ‘if you want to be anybody, or make money in Pittsburg, it is necessary to be in the political swim and on the side of the city ring.’”

This is corruption, but it is called “good business,” and it is worse than politics.

It was a quarrel among the grafters of Minneapolis that gave the grand jury a chance there. It was a low row among the grafters of St. Louis that gave Joseph W. Folk his opening. And so in Pittsburg it was in a fight between Quay and Magee that the Municipal League saw its opportunity.

To Quay it was the other way around. The rising of the people of Pittsburg was an opportunity for him. He and Magee had never got along well together, and they were falling out and having their differences adjusted by Flinn and others every few years. The “mutual business advantage” agreement was to have closed one of these rows. The fight of 1895–96 was an especially bitter one, and it did not close with the “harmony” that was patched up. Magee and Flinn and Boss Martin of Philadelphia set out to kill Quay politically, and he, driven thus into one of those “fights for his life” which make his career so interesting, hearing the grumbling in Philadelphia and seeing the revolt of the citizens of Pittsburg, stepped boldly forth upon a platform for reform, especially to stop the “use of money for the corruption of our cities.” From Quay this was comical, but the Pittsburgers were too serious to laugh. They were fighting for their life, too, so to speak, and the sight of a boss on their side must have encouraged those business men who “found it easier to deal with a boss than with the people’s representatives.” However that may be, a majority of the ballots cast in the municipal election of Pittsburg in February, 1896, were against the ring.

This isn’t history. According to the records the reform ticket was defeated by about 1,000 votes. The returns up to one o’clock on the morning after election showed George W. Guthrie far ahead for mayor; then all returns ceased suddenly, and when the count came in officially, a few days later, the ring had won. But besides the prima facie evidence of fraud, the ringsters afterward told in confidence not only that Mr. Guthrie was counted out, but how it was done. Mr. Guthrie’s appeal to the courts, however, for a recount was denied. The courts held that the secret ballot law forbade the opening of the ballot boxes.

Thus the ring held Pittsburg—but not the Pittsburgers. They saw Quay in control of the Legislature, Quay the reformer, who would help them. So they drew a charter for Pittsburg which would restore the city to the people. Quay saw the instrument, and he approved it; he promised to have it passed. The League, the Chamber of Commerce, and other representative bodies, all encouraged by the outlook for victory, sent to Harrisburg committees to urge their charter, and their orators poured forth upon the Magee-Flinn ring a flood of, not invective, but facts, specifications of outrage, and the abuse of absolute power. Their charter went booming along through its first and second readings, Quay and the Magee-Flinn crowd fighting inch by inch. All looked well, when suddenly there was silence. Quay was dealing with his enemies, and the charter was his club. He wanted to go back to the Senate, and he went. The Pittsburgers saw him elected, saw him go, but their charter they saw no more. And such is the State of Pennsylvania that this man who did this thing to Pittsburg, and has done the like again and again to all cities and all interests—even politicians—he is the boss of Pennsylvania to-day!

The good men of Pittsburg gave up, and for four years the essential story of the government of the city is a mere thread in the personal history of the quarrels of the bosses in State politics. Magee wanted to go to the United States Senate, and he had with him Boss Martin and John Wanamaker of Philadelphia, as well as his own Flinn. Quay turned on the city bosses, and, undermining their power, soon had Martin beaten in Philadelphia. To overthrow Magee was a harder task, and Quay might never have accomplished it had not Magee’s health failed, causing him to be much away. Pittsburg was left to Flinn, and his masterfulness, unmitigated by Magee, made trouble. The crisis came out of a row Flinn had with his Director of Public Works, E. M. Bigelow, a man as dictatorial as Flinn himself. Bigelow threw open to competition certain contracts. Flinn, in exasperation, had the councils throw out the director and put in his place a man who restored the old specifications.

This enraged Thomas Steele Bigelow, E. M. Bigelow’s brother, and another nephew of old Squire Steele. Tom had an old grudge against Magee, dating from the early days of traction deals. He was rich, he knew something of politics, and he believed in the power of money in the game. Going straight to Harrisburg, he took charge of Quay’s fight for Senator, spent his own money and won; and he beat Magee, which was his first purpose.

But he was not satisfied yet. The Pittsburgers, aroused to fresh hope by the new fight of the bosses, were encouraged also by the news that the census of 1900 put a second city, Scranton, into “cities of the second class.” New laws had to be drawn for both. Pittsburg saw a chance for a good charter. Tom Bigelow saw a chance to finish the Magee-Flinn ring, and he had William B. Rogers, a man whom the city trusted, draw the famous “Ripper Bill”! This was originally a good charter, concentrating power in the mayor, but changes were introduced into it to enable the Governor to remove and appoint mayors, or recorders, as they were to be called, at will until April, 1903, when the first elected recorder was to take office. This was Bigelow’s device to rid Pittsburg of the ring office holders. But Magee was not dead yet. He and Flinn saw Governor Stone, and when the Governor ripped out the ring mayor, he appointed as recorder Major A. M. Brown, a lawyer well thought of in Pittsburg.

Major Brown, however, kept all but one of the ring heads of the departments. This disappointed the people; it was a defeat for Bigelow; for the ring it was a triumph. Without Magee, however, Flinn could not hold his fellows in their joy, and they went to excesses which exasperated Major Brown and gave Bigelow an excuse for urging him to action. Major Brown suddenly removed the heads of the ring and began a thorough reorganization of the government. This reversed emotions, but not for long. The ring leaders saw Governor Stone again, and he ripped out Bigelow’s Brown and appointed in his place a ring Brown. Thus the ring was restored to full control under a charter which increased their power.

But the outrageous abuse of the Governor’s unusual power over the city incensed the people of Pittsburg. A postscript which Governor Stone added to his announcement of the appointment of the new recorder did not help matters; it was a denial that he had been bribed. The Pittsburgers had not heard of any bribery, but the postscript gave currency to a definite report that the ring—its banks, its corporations, and its bosses—had raised an enormous fund to pay the Governor for his interference in the city, and this pointed the intense feelings of the citizens. They prepared to beat the ring at an election to be held in February, 1902, for Comptroller and half of the councils. A Citizens’ party was organized. The campaign was an excited one; both sides did their best, and the vote polled was the largest ever known in Pittsburg. Even the ring made a record. The citizens won, however, and by a majority of 8,000.

This showed the people what they could do when they tried, and they were so elated that they went into the next election and carried the county—the stronghold of the ring. But they now had a party to look out for, and they did not look out for it. They neglected it just as they had the city. Tom Bigelow knew the value of a majority party; he had appreciated the Citizens’ from the start. Indeed he may have started it. All the reformers know is that the committee which called the Citizens’ Party into existence was made up of twenty-five men—five old Municipal Leaguers, the rest a “miscellaneous lot.” They did not bother then about that. They knew Tom Bigelow, but he did not show himself, and the new party went on confidently with its passionate work.

When the time came for the great election, that for recorder this year (1903), the citizens woke up one day and found Tom Bigelow the boss of their party. How he came there they did not exactly know; but there he was in full possession, and there with him was the “miscellaneous lot” on the committee. Moreover, Bigelow was applying with vigor regular machine methods. It was all very astonishing, but very significant. Magee was dead; Flinn’s end was in sight; but there was the Boss, the everlasting American Boss, as large as life. The good citizens were shocked; their dilemma was ridiculous, but it was serious too. Helpless, they watched. Bigelow nominated for recorder a man they never would have chosen. Flinn put up a better man, hoping to catch the citizens, and when these said they could see Flinn behind his candidate, he said, “No; I am out of politics. When Magee died I died politically, too.” Nobody would believe him. The decent Democrats hoped to retrieve their party and offer a way out, but Bigelow went into their convention with his money and the wretched old organization sold out. The smell of money on the Citizens’ side attracted to it the grafters, the rats from Flinn’s sinking ship; many of the corporations went over, and pretty soon it was understood that the railroads had come to a settlement among themselves and with the new boss, on the basis of an agreement said to contain five specifications of grants from the city. The temptation to vote for Flinn’s man was strong, but the old reformers seemed to feel that the only thing to do was to finish Flinn now and take care of Tom Bigelow later. This view prevailed and Tom Bigelow won. This is the way the best men in Pittsburg put it: “We have smashed a ring and we have wound another around us. Now we have got to smash that.”

There is the spirit of this city as I understand it. Craven as it was for years, corrupted high and low, Pittsburg did rise; it shook off the superstition of partisanship in municipal politics; beaten, it rose again; and now, when it might have boasted of a triumph, it saw straight: a defeat. The old fighters, undeceived and undeceiving, humiliated but undaunted, said simply: “All we have got to do is to begin all over again.” Meanwhile, however, Pittsburg has developed some young men, and with an inheritance of this same spirit, they are going to try out in their own way. The older men undertook to save the city with a majority party and they lost the party. The younger men have formed a Voters’ Civic League, which proposes to swing from one party to another that minority of disinterested citizens which is always willing to be led, and thus raise the standard of candidates and improve the character of regular party government. Tom Bigelow intended to capture the old Flinn organization, combine it with his Citizens’ party, and rule as Magee did with one party, a union of all parties. If he should do this, the young reformers would have no two parties to choose between; but there stand the old fighters ready to rebuild a Citizens’ party under that or any other name. Whatever course is taken, however, something will be done in Pittsburg, or tried, at least, for good government, and after the cowardice and corruption shamelessly displayed in other cities, the effort of Pittsburg, pitiful as it is, is a spectacle good for American self-respect, and its sturdiness is a promise for poor old Pennsylvania.

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1904, before the cutoff of January 1, 1929. It was adapted by the Observatory from a version produced by Wikisource contributors.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1936, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 87 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.- ↑ All the street railways terminating in the city of Pittsburg were in 1901 consolidated into the Pittsburg Railways Company, operating 404 miles of track, under an approximate capitalization of $84,000,000. In their statement, issued July 1, 1902, they report gross earnings for 1901 as $7,081,452.82. Out of this they paid a car tax for 1902 to the city of Pittsburg of $20,099.94. At the ordinary rate of 5 per cent on gross earnings the tax would have been $354,072.60.