The Intricate Connection of Birdsongs to Human Language

Listening to birds benefits our mental health, leading to less stress and paranoia.

Introduction

Birdsongs have inspired poets and lovers, becoming one of the philosophical focal points in ancient Greece and Rome. They have also led to several long-ago debates about the relationship between birdsong and human language.

“A robust body of evidence accrued over approximately 100 years demonstrates striking analogies between birdsong and speech, both learned forms of vocalization,” states the Royal Society journal.

Some thinkers have argued that humans are the only rational animals since they have a language, unlike nonhuman animals. Yet bird communications through melodious songs sound very much like a language, casting doubts on these views. No nonhuman animals other than birds, specifically songbirds, display such fine musical articulation and use these communication skills among their species.

“Humans and songbirds share the key trait of vocal learning, manifested in speech and song, respectively. Striking analogies between these behaviors include that both are acquired during developmental critical periods when the brain's ability for vocal learning peaks,” adds the Royal Society article.

The Philosophical View on Songbirds

Aristotle, a philosopher and scientist educated at Plato’s Academy, first systematically studied birds and all other known living creatures. In addition to his other works, he wrote the monumental History of Animals (the original title in Greek was the more modest Inquiries on Animals). It remained the authoritative source for Western zoology until the 16th century.

Aristotle asked the questions of what and why. He already knew, ages ago, that birds learn their songs. In History of Animals, he states:

“Of little birds, some sing a different note from the parent birds, if they have been removed from the nest and have heard other birds singing; and a mother-nightingale has been observed to give lessons in singing to a young bird, from which spectacle we might obviously infer that the song of the bird was not equally congenital with mere voice, but was something capable of modification and of improvement.”

In particular, parrots may be able to closely mimic the human voice due to the use of their tongue. According to popular opinion, in ancient Greece, parrots didn’t produce melodies but had a semi-human voice and could learn Greek. Aristotle didn’t buy it. According to him, only humans had logos [reason] and the ability to use language to communicate. What parrots did was simply mimicry. Fast-forward to the poignant story of “Humboldt’s talking parrot.”

In 1799, during his explorations along the Orinoco River, German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt “stayed with a local Indigenous Carib tribe near the isolated village of Maypures,” located deep in the Venezuelan jungle. The Indigenous inhabitants kept tame parrots in cages and taught them how to speak. But among them was one bird that “sounded unusual.” When Humboldt asked why, he learned that the parrot had belonged to a nearby enemy tribe who were driven from their home village and land. The few surviving members fled to a tiny islet perched between the river rapids. It was there where their culture and their lingo endured for a few more years until the last tribesman died. The only creature “who spoke their language” was the talking parrot.

Fortunately, Humboldt transcribed the parrot’s vocabulary phonetically in his journal. This helped rescue a portion of the vanished tribe’s language from extinction.

Today, some linguists accept this story as a metaphor for the vulnerability of languages, with one lost every 40 days. Still, skeptics wonder if the tale is accurate. Whatever the case may be, Humboldt himself reports in the second volume of his Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America, During the Year 1799-1804, published soon after his return to Europe, about his stay with a group of natives in an isolated village beside a waterfall on the Orinoco River:

“A tradition circulates among the Guahibos, that the warlike Atures [another tribe], pursued by the Caribs, escaped to the rocks that rise in the middle of the Great Cataracts; and there that nation, heretofore so numerous, became gradually extinct, as well as its language.”

This animal-supporting mindset has stood against the rise of Christianity, which held that all other beings were created to serve humans and their needs. Consequently, the Church favored the side that regarded animals as irrational. Therefore, Aristotle governed supreme in religious teachings, philosophy, and scholastic learning within universities until the arrival of the 16th century.

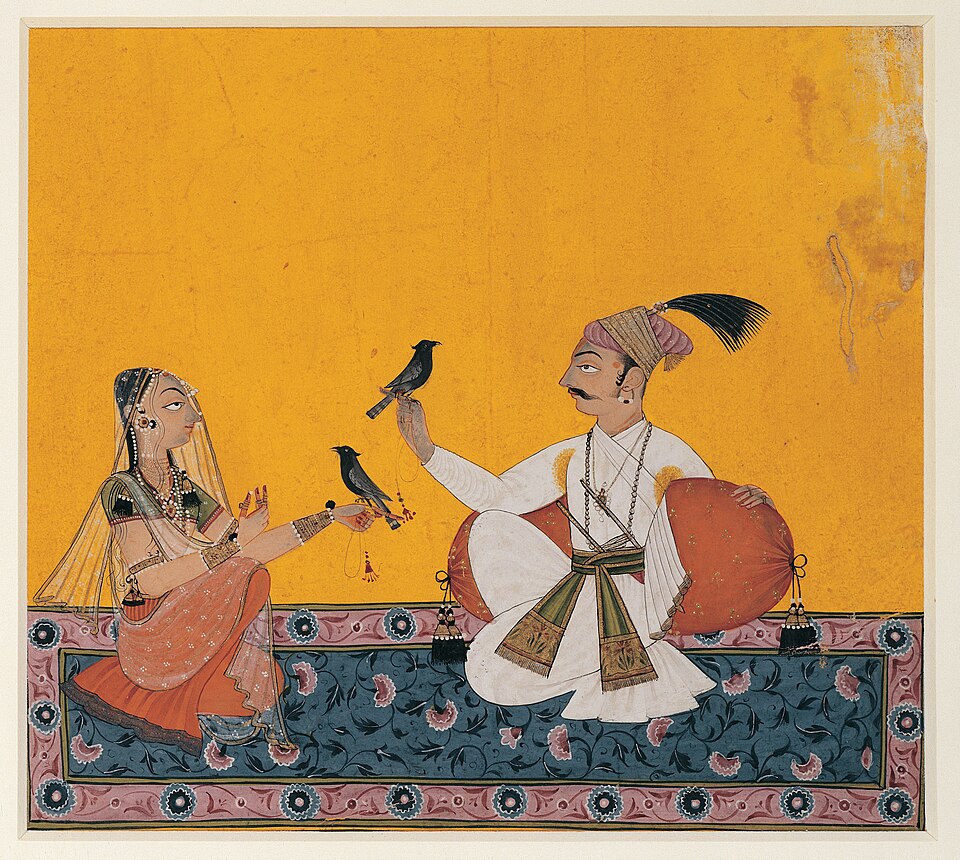

Despite the belief that animals were inferior to humans, people had their own ways. Songbirds were widely liked and were memorialized thanks to the great poets of the Middle Ages. Both the French Provencal troubadours and the German and Austrian Minnesingers cherished singing birds and, above all, nightingales. These are a few lines from Walter von der Vogelweide, who used a last name that means “of the bird meadow:”

“Besides the forest in the vale

Tándaradéi,

Sweetly sang the nightingale.”

According to legend, the poet left a will requesting that the birds at his tomb be fed daily.

The Language of Animals

In the second half of the 18th century, the philosophical focus shifted from the age-old argument that nonhuman animals lacked reason to a serious study of animal language. German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder’s 1772 Treatise on the Origin of Language asserts that “these groans, these sounds, are language” through which the animals communicate. Even if nonhuman animals are not rational, they have, for example, the language of pain. For human and nonhuman beings, “there is a language…which is an immediate law of nature,” Herder adds.

Hein van den Berg, an assistant professor from the University of Amsterdam, published an excellent paper on these developments in 2022. He writes, “Herder affirmed that each animal species has a distinctive language.” And that especially includes songbirds.

In addition, Herder endorsed sympathy and empathy as qualities that may enable interspecies communications. Humans don’t understand what animals say, and animals do not comprehend human concepts and speech. But this can be surmounted by Einfühlung, slipping into the nonhuman being’s skin to understand how it feels. It is like “walking in someone’s shoes.” It is a word Herder invented. Perhaps birdsong is so beloved by humans because it enables this feeling to resonate instantly and naturally. A person usually reacts to a singing bird with spontaneous and joyful emotions.

Interestingly, Herder’s work on empathy almost certainly provides the foundation for the Seattle Aquarium’s empathy-themed programs. The aquarium fosters empathy for wildlife, develops teacher resources, offers empathy fellowships, operates an empathy café, conducts empathy workshops in Seattle and around the country, and holds biennial conferences.

Arthur Schopenhauer, frequently dubbed the philosopher of artists and pessimists, was one of the earliest supporters of animal rights. He was blunt about his views in his book The Basis of Morality:

“The assumption that animals are without rights and the illusion that our treatment of them has no moral significance is a positively outrageous example of Western crudity and barbarity. Universal compassion is the only guarantee of morality.”

Hindu philosophies and Buddhism greatly influenced Schopenhauer, who respected and supported animals. He was also prescient, anticipating current conditions by writing, “The world is not a factory, and animals are not products for our use.”

While philosophers have emphasized birds and their songs, what did scientists, researchers, ornithologists, and regular bird lovers learn about birds’ origins?

Evolution of Birds: The Scientific Perspective

Amazingly, our beautiful birds started as not-so-handsome dinosaurs. The evidence shows that they emerged from theropod dinosaurs during the Late Jurassic period, some 150 million years ago. The Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin displays the most complete specimen of Archaeopteryx, regarded for more than a century as the oldest bird fossil from the transitional phase of evolution from dinosaur to bird. Resembling a raven, the fossil was unearthed in 1860. An additional 12 fossils, most with imprints of feathers, were discovered afterward. All of them came from the Solnhofen Limestone formation in Bavaria, Germany. In recent decades, however, a few different small and feathered dinosaurs were excavated in other locations. These may, likewise, have a role in the story of the evolution of birds.

Songbirds are a suborder of birds, specifically of perching birds called passerines or oscines. There are more than 4,000 species, all of which have a unique vocal organ: the syrinx.

The songbirds can execute various tasks and performances with their vocal organs. They use short, practical calls to communicate details about food or predators and long, learned, and practiced songs to find and seduce mates, defend territories, compete, and develop social bonds. Perhaps even more fascinating is that they all do it in their own way. For example, the males of the highly social Australian zebra finches do not sing to defend territory and do not perform to impress potential mates. They wait until they find their love partner and then serenade her, often daily and for years to come.

Songbirds are actively involved in learning, listening to, and practicing the complex creations we call songs. Birds of the same species use different dialects in various locations.

Peter Marler, a neurobiologist at the University of California, Davis, did groundbreaking work on how birds talk. He told the Sacramento Bee in 1997 that “[d]ialects [in birds] are so well marked that if you really know your white-crowned sparrows, you’ll know where you are in California.” Once Marler’s student, Fernando Nottebohm was already fascinated by birds as a boy growing up in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is Dorothea L. Leonhardt, a professor emeritus at The Rockefeller University. Nottebohm “discovered that adult canaries regenerate neurons from neural stem cells. … [and believes] doctors may one day be able to replace neurons in the human brain to offset the effects of disease, injury, or aging,” according to the Franklin Institute.

Scientists have also ascertained that songbirds hear their melodies differently than humans. People have dissimilar hearing capabilities and can’t discern the nuances and subtleties vital to birds. Many composers have used bird sounds, including Vivaldi in “The Four Seasons,” Handel in the aria “Sweet Bird” in L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, Beethoven in his “Symphony No. 3,” and in “Symphony No. 6,” in which you can hear a nightingale (played by the flute), a quail (oboe) and a cuckoo (clarinet). Nightingales can be heard in the compositions of Mendelssohn, Liszt, Grieg, Ravel, and various others.

Birds have, in fact, influenced our musical creativity since the times of the hunter-gatherers. “Birdsong has inspired musicians from Bob Marley to Mozart and perhaps as far back as the first hunter-gatherers who banged out a beat. And a growing body of research shows that human musicians’ affinity toward birdsong has a strong scientific basis,” states a 2023 New York Times article.

Birds have the habit of practicing their singing daily. Songbirds “require daily vocal exercise to first gain and subsequently maintain peak vocal muscle performance,” according to a December 2023 Nature article.

But that’s not all. Not only has the field of birdsong biology experienced rapid growth, but studies about vocal learning, neurobiological aspects, and theory of mind insights have expanded our knowledge. A 2020 article titled “Birds are Philosophy Professors” credits the capacity for flight and highlights the skill of gliding when birds are confronted by adverse conditions. “When faced with torrential wind, they fully acknowledge nature’s forces are stronger, and the best way to deal with it is to simply be in it. … Birds stop flapping their wings and they simply glide. This awareness is crucial because they would otherwise spend energy flapping that wouldn’t amount to any progress,” points out the article.

A quote by the Stoic Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius stresses the wisdom of such behavior: “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.”

Birds act accordingly. Resistance to the stronger forces of nature would waste energy, so they wait, gliding, until things improve.

Surprisingly, birds also can remember humans. The evidence for this is clear. For instance, species like robins, mockingbirds, and pigeons have “some of the most well-documented cases of facial recognition,” states Chirp Nature Center. Pigeons even react to facial expressions. Be kind, and they will recall. Chase them away, and they will not forget. Moreover, birds certainly remember dependable food and water sources and show up daily; suddenly, there they are, just stopping by to eat and drink.

How Birdsongs Help Humans

But these beneficial factors are a two-way street. Humans also gain great psychological value from their interaction with songbirds. An article in Wild Bird Feeding Institute reports on a recent study by Emil Stobbe of the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin that explores the mental health benefits of soothing bird melodies. Among them are stress reduction, mood enhancement, and connection to nature. “[F]or the first time, beneficial, medium-sized effects of birdsong soundscapes were demonstrated, reducing paranoia,” the study states.

Soldiers in the trenches of World War I knew this already. The poem “Dead Man’s Dump” gives voice to their feelings, stating that while “the air [was]… loud with death,” the soldiers gained resilience and kept their sanity by listening to the song of birds, counterbalancing the noisy chaos of war. Michael Guida wrote a lovely, powerful book called Listening to British Nature.

“According to one analysis, living in an area with 10 percent higher avian diversity rates increases life satisfaction 1.53 times more than a higher salary,” points out the Conservation magazine.

Another small book, A Short Philosophy of Birds—written by French ornithologist Philippe J. Dubois and Elise Rousseau, philosopher and author of several works on nature and animals—is a delightful gem overflowing with stories and details about birds and human life. The book also highlights the mortal danger birds are in. We don’t see this since it happens discreetly, but since 1970, a staggering 2.9 billion breeding adult birds have vanished across North America as of 2020.

The book reflects on the threat humans pose to the existence of birds:

“Birds hide away to die, so they say. And it’s true. Have you ever seen a dead swallow, except for one… hit by a car or flown into a pane of glass?”

Meanwhile, the philosophical association between birdsong and human language is still as relevant as in antiquity. A 2013 linguistic study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a 2014 genetic study at Duke University found that early humans may have acquired language by imitating birdsong and that identical genes are activated when learning to sing (birds) or talk (humans).

“If early humans developed their own language by imitating birdsong, it’s nothing short of incredible that this linguistic history was expressed in creation myths several hundred thousand years after the fact, from Africa to Kansas,” states a 2023 Patheos article.

The Hopi Tribe, a sovereign nation located in northeastern Arizona, emerged from the underworld with the help of a singing mockingbird who gave them the gift of language. According to the Osage of Kansas, “their ancestral souls were once without bodies until a redbird volunteered itself to make human children by transforming its wings into arms, its beak into a nose and by passing on the gift of language.” Birds are similarly key players in various creation myths worldwide.

The profound connection between birdsong and human language continues to captivate scientists, philosophers, and artists alike. From Aristotle’s early observations to modern linguistic and neurological studies, the parallels between avian and human communication remain striking. Birds not only inspire poetry and music but also challenge long-held beliefs about the exclusivity of human language and cognition. Their songs offer a sense of wonder, a bridge between species, and even psychological benefits to those who listen.

As we learn more about songbirds’ intelligence and emotional depth, we are reminded of our shared evolutionary past and the importance of preserving these creatures and their habitats. Whether through scientific research, philosophical inquiry, or personal appreciation, birdsongs continue to enrich human understanding of language, empathy, and the natural world.