The Curious Craze for ‘Little Switzerlands’ in 19th-Century England

Ornamental gardens and Alpine-style cottages transformed the English countryside into miniature Swiss landscapes, blending Romantic ideals with playful kitsch.

“Nothing can be uglier, per se, than a Swiss cottage, or anything more beautiful under its precise circumstances.” —James Fenimore Cooper, Home as Found: Sequel to Homeward Bound (1838)

Visitors to Biggleswade, Bedfordshire, might encounter the historic airplanes hangared at Shuttleworth, while also discovering the country estate’s Swiss Garden—charming, if uncanny, territory. The museum’s planes resemble illustrations from children’s books, delighting younger audiences. Yet the ornate ironmongery and diminutive duck ponds of Shuttleworth’s other main landscaped attraction can surprise. The neatly-turfed hillocks are cute and hardly confounding on their own, but unexpected for anyone familiar with the rugged, startling, and at times terrifying Helvetian mountains. The garden’s centerpiece is a thatched and oddly contrived “Swiss” cottage that bears little resemblance to alpine huts. A white peacock wandering the grounds adds to the sense of a scene that is visually compelling, yet curiously contrary to expectations.

Shuttleworth’s Swiss Garden evokes a broader history that reaches back to the 18th century, not only to Switzerland but also across Europe and to North America, before returning to England. Around 1800, a version of the aesthetic sublime turned sweet, while the pastoral, with its lakes and cottages, morphed into the picturesque: an agreeable aesthetic of landscape, framed or staged for tourists’ pleasure. James Fenimore Cooper’s characters in the 1838 novel Home as Found complain of the architectural blight of “Swiss Cottages” afflicting the banks of the Hudson amid a building boom in New York. Cooper had hiked in the Swiss Alps himself and bemoaned an inauthentic imaginary that was now imitated across the world for easy, uncritical, and comfortable amusement. The image of Swissness became kitsch—especially in England during Georgian, Victorian, and Edwardian times, when a fashion for “Little Switzerlands” peaked. Alpine scenery no longer required travel abroad, as Swiss landscapes were brought home like souvenirs and domesticated as ornaments for the English countryside.

Now that popular culture has climbed down from the height of that craze, we might not know what to make of Swiss Gardens in the English Shires today. Perhaps the absence of context and cultural history in our present age is why we can cast an eye (at once appreciative and naïve) on these eclectic, eccentric mountains in miniature. They are no longer stunningly beautiful, nor are they fashionably delightful. As a weird hodgepodge of styles presented as Helveticism, we can but enjoy these Little Switzerlands for whatever they are now, wherever they are. But what were these fairy-tale-like, small Alpine attractions like once upon a time?

Romantic Mountains in Miniature

The story of Swiss Gardens (like the one at Shuttleworth) begins in 1790, when William Wordsworth stopped, awestruck, while on a walking tour in Switzerland. He was astounded not just by the landscape, but also by an intricate model of Lake Lucerne, the surrounding Alps, and characterful cottages, all to scale. Wordsworth did not observe the constructed scene alone, given that the finely measured mountain-scape, created by the surveyor Franz Ludwig Pfyffer von Wyher, was on display to groups of tourists. Nor was Wordsworth the only Englishman or foreigner to traverse Swiss nature. No lonely wanderer, he was joined by a friend, Robert Jones, and accompanied by a whole generation of the European social and intellectual elite. They travelled to Switzerland in search of wonder, sublime scenery, and high ideals.

Switzerland was romanticized as the home of freedom and of intense sentimental attachment. And like most idealized concepts people coalesce around, Swiss freedom was vague: anything to everyone. The freer space was understood in individual, political, and spiritual terms. If a nation is an “imagined community,” to speak with the theorist Benedict Anderson, then 18th-century Switzerland primarily emerged in the minds of Enlightenment thinkers as a mythical, Arcadian place. A fictional idyll rather than a realistic image, this “Switzerland” could easily be packaged and moved elsewhere. Swiss authors such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau in French and Salomon Gessner in German shaped the country’s image in print, as particularly evidenced in Rousseau’s 1761 novel Julie, which became a pan-European success story. Rousseau’s popularity was due, in no small part, to his depiction of an exoticized Swiss landscape that homes in on the senses. What is more, in Julie, Switzerland stands in as a superior example of aesthetic sensuality and homeliness compared to the rest of the world:

The nearer I got to Switzerland, the more emotion I felt. The instant when from the heights of the Jura I sighted Lake Geneva was an instant of ecstasy and ravishment. The sight of my country, of that country so cherished where torrents of pleasures had flooded my heart; the air of the Alps so wholesome and pure; the sweet air of the fatherland, more fragrant than the perfumes of the Orient; that rich and fertile land, that unique countryside, the most beautiful that ever met human eye; that charming abode like nothing I had found in circling the earth; the sight of a happy and free people; the mildness of the season, the calmness of the Clime; a thousand delightful memories that reawakened all the sentiments I had tasted; all these things threw me into transports I cannot describe, and seemed to restore to me all at once the enjoyment of my entire life.

If the strange, stylized image of Switzerland abroad began as a literary narrative, it was also shaped by linguistic, artistic, and cultural exchange. Switzerland’s German dialects may have been substituted by the Saxon (or “Meißen”) standard as a supposedly Enlightened literary language, but the landscape of the German Meißen hills was soon framed as Swiss: it was named “die Sächsische Schweiz,” or Saxon Switzerland, following comparisons by resident Swiss artists. Over in England, painters from Berne, Switzerland’s capital, toured Derbyshire to capture its natural scenery, which they believed was similar to that of their homeland. The Swiss exported the picturesque familiarity of their native country, drawing connections with foreign cultures from that perspective.

Wordsworth, too, engaged in the pursuit of analogy. His own emotions overflowed as he composed a sonnet at the top of the Gotthard Pass about a rural legend: The apocryphal story that a cowherd’s melody, traditionally played on an alphorn, once caused a Swiss man in foreign lands to die of homesickness. Wordsworth writes that we should not interpret the folktale as “fabulous.” Indeed, he invokes what is often called the “Swiss illness” to explain his own longing for home as the “Lake District.” And so, the Swiss myth influenced the yearning tone of Wordsworth’s English Romanticism.

However, literal comparisons between the landscapes of Switzerland and England took a little longer to gain ground. If, in a letter from 1790 sent from Lake Constance to his sister, Dorothy, William claimed that “the scenes of Switzerland have no resemblance to any I have found in England,” this would soon change. Once home, Wordsworth molded the English scenery in response to what he had seen abroad. As much inspired by Wyler’s relief of the Alpine landscape as by Helvetic myth, Wordsworth began to draw realistic analogies between the Swiss and English countryside in his poetry and criticism. Although the Lake District is geologically mountainous, its landscape is more undulating and less extreme than that of the four cantons surrounding the Vierwaldstättersee (Lake Lucerne). Smaller in magnitude, yet all the greater in variety, the Lake District is gentler; strong winds don’t blow you about in Cumbria as much as they can in Switzerland. “A happy proportion of component parts is indeed noticeable among the landscapes of the North of England,” writes Wordsworth in an anonymous essay that accompanied a luxury edition of prints in 1810 (which was expanded and published in his name as a Guide to the Lakes in later editions). Further, the English proportionality of mountains is “essential to a perfect picture”, and surpasses “the scenes of Scotland, and, in a still greater degree, those of Switzerland.”

Swissness was shrunk and overlaid onto the English countryside, not only by Wordsworth, for his analogies were already platitudinous. (In composing his Guide, Wordsworth had read Thomas West’s 1778 Guide to the Lakes, which addresses those “who have traversed the Alps” and promises that “the travelled visitor [exploring] the Cumbrian lakes and mountains, will not be disappointed”). But our Lake District poet conceived a popular comparison more theoretically, staking out a claim about sublimity and smallness for those who might not have been to Switzerland and could no longer reach it. In 1810, Wordsworth prefaced his reflections by recollecting the model he had seen in Lucerne 20 years beforehand, which he now considered from an aesthetic point of view:

The Spectator ascends a little platform, and sees mountains, lakes, glaciers, rivers, woods, waterfalls, and valleys, with their cottages, and every other object contained in them, lying at his feet; all things being represented in their appropriate colours. It may be easily conceived that this exhibition affords an exquisite delight to the imagination, tempting it to wander at will from valley to valley, mountain to mountain, through the deepest recesses of the Alps. But it supplies also a more substantial pleasure: for the sublime and beautiful region, with all its hidden treasures, and their bearings and relations to each other, is thereby comprehended and understood at once.

As Wordsworth remembers the miniature scene, it was not only delightful, but also pleasurable in a “solid” and “substantial” way. The Alps at scale allowed him to survey the scenery in one go, like a diorama, and, supposedly, to understand its overall effect. Wordsworth goes on to admire a “tranquil sublimity”, which was also apparently true of the English Lake District.

For any earlier 18th-century readers, seeing the sublime as sedate would have been a contradiction in terms. Sublimity—and above all, the Alpine mountain-scape—was supposed to be awesome yet scary. The sense of terror that lay in wait for the observer of the Alps was, in part, thanks to the enduring influence of Edmund Burke’s 1757 treatise on the sublime (his section titles say it all: Terror, Obscurity, Privation, Vastness, Infinity). Immanuel Kant’s equally tremendous discussion of “mathematical” and “dynamical” sublimity also transformed both aesthetic theories and intellectual alpine travelers’ experiences of his day. A new, tranquil, more domesticated, and overly diminutive sublime shrunk to scale now came to define England’s rolling hills and mountains for Wordsworth, a sublimity that “depends more upon form and relation of objects to each other than upon their actual magnitude.” His conception of the English small sublime did not fit the existing European grand theories. But it was an image that stuck.

Wordsworth’s analogies represented his own nation all the better; yet his motives did not stem merely from national competition. For most Britons during the first decade or so of the early 19th century, Switzerland could be accessed only in the mind. The Napoleonic wars of 1803 to 1815 meant that the tourist population in general had to retreat and stay at home. More significantly, the age of conflict was a clear cause of patriotism. As Patrick Vincent pointed out, during this period of warring, Switzerland was staged as a setting for anti-Jacobin morality plays in Britain. Although not all poets, staycationers, and armchair travelers used Switzerland as an excuse for comparative national pride, the Alps could no longer be idealized entirely.

That wartime tendency held true across Europe. The German Friedrich Schiller not only expounded on and nuanced the sublime (or das Erhabene) but also dramatized the Wilhelm Tell legend in 1804 with a degree of ambivalence. On the killing of the tyrannical overlord Geßler, Tell declares that the mountain huts (or “cottages” in the words of the mid-19th century translator into English) are free of Habsburg control by proxy—and innocence is thereby safeguarded. Schiller’s play reworks a medieval Alpine narrative of self-sufficiency and greater democratic governance, for a political present in which Switzerland had once again become a confederation (following the collapse of Napoleon’s centralized Helvetic Republic the year before, and having been a sister state of France since 1798). Schiller romanticizes Swiss folklore and society as an important Germanic story of liberation. However, Wilhelm Tell is also ambiguous in its assessment of how revolutionary politics really work. The Enlightenment idyll was marred by historical reality around the same time as the sublime was split into new subcategories.

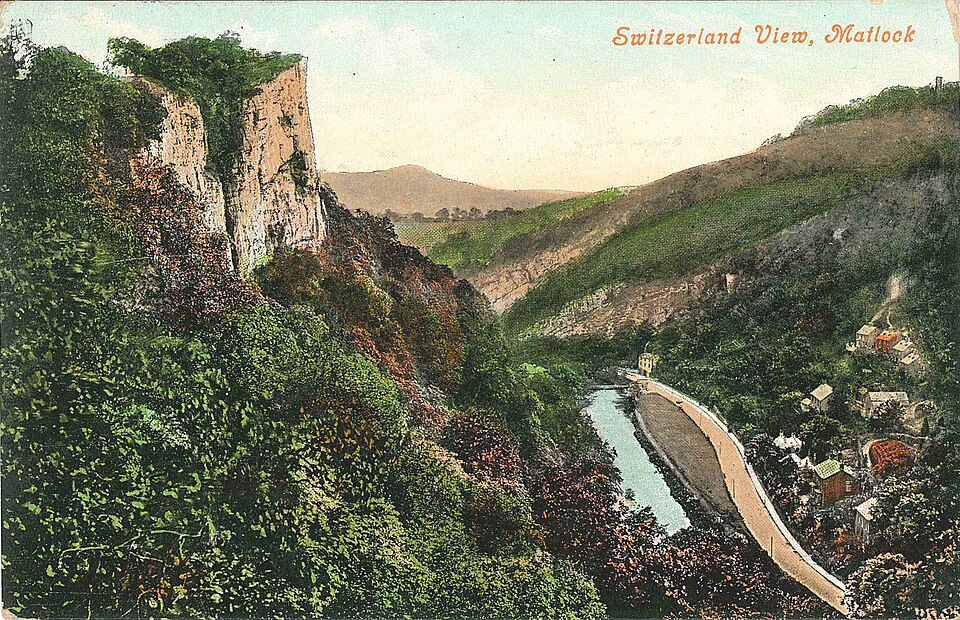

When peace was restored, international travel resumed. Even as more people experienced Switzerland firsthand, the old fictions of Swiss authenticity were reissued in many minds, and the country’s simple beauty and Arcadian happiness seemed straightforward once again. Wordsworth returned to Switzerland, accompanied by Dorothy and his wife, Mary. Other English Romantics vacationed there as well: Percy and Mary Shelley famously stayed with Lord Byron near Lake Geneva, where they told stories to each other through the night that inspired the eventual rise of Frankenstein in 1818. Mary Shelley’s Gothic novel compares Derbyshire’s Matlock to “the scenery of Switzerland; but everything is on a lower scale, and the green hills want the crown of distant white Alps.” As well as in Cumberland and Westmorland, the titular character fancies himself “among the Swiss mountains.” And during correspondence written from Jura while observing the mountains, Mary Shelley casts Switzerland’s famed alpenglow as quintessentially English, noting “that glowing rose-like hue which is observed in England to attend on the clouds of an autumnal sky when daylight is almost gone.” Literary analogies between England and Switzerland were either explicitly positive or passing observations that went unquestioned.

Matlock in Derbyshire and the Lake District were both in demand with day-trippers and domestic holiday-makers by this time, similar to the Alps (Jane Austen bemoaned the absence of a friend in 1817, who was “frisked off like half England, into Switzerland”). Irritated that they made the place “another Keswick,” Percy Shelley complained of tourists as he tried to picnic on the mountainside near Chamonix in 1816. Meanwhile, in Byron’s journal from the same trip, he recalls overhearing an English woman exclaim, “‘Did you ever see anything more rural?’—as if it was Highgate, or Hampstead, or Brompton, or Hayes,” Ironically, though, the Romantic writers themselves contributed to this very tourism as travelers and as authors whose words were taken out of their mouths and printed in pocket guides. In 1817, Byron wrote from Venice to ask Thomas Moore if he had ever been to Dovedale in the southern Peak District, assuring him that “there are things in Derbyshire as noble as Greece or Switzerland.” Guidebooks soon plucked that quotation, and some even changed it. For example, in 1879, the language was changed from “things” to “prospects,” implicitly relocating the view to Matlock Bath, approximately 15 miles farther north.

The Victorian travel journalist with a liberal attitude to literary lines proceeds to defend the comparison between Matlock and Switzerland in Wordsworth-like logic, stating, “The Peak is Alpine on a reduced scale; it is Switzerland seen through a lessening lens; its hills are mountains in miniature.” A German guidebook to Luxembourg from 1934 that I picked up in Hay-on-Wye over the summer, a bookish Welsh border town in the small shadows of the Brecon Beacons, justifies the Petite Suisse Luxembourgeoise in the same way, discussing smallness relative to Switzerland, and magnitude (at a mere 400 meters) when compared to the surrounding Luxembourg flatlands. The idea of pocket-sized Swiss mountains was pan-European at the time, but in England it had an especially poetic inflection from the nation’s literary canon. The above line from the English journalist is similar wording to that of which Percy Shelley had used when writing to Thomas Peacock from the Alps in 1816: “The scene, at the distance of half-a-mile from Cluses, differs from that of Matlock in little else than in the immensity of its proportions.”

The legacy of Romantic musing has not only been canonical literature about Switzerland, it seems, but also signposts, postcards, and tourist brochures. The slogans of the tourist trade were thus also the commonplaces of English Romanticism. Old postcards in Buxton Museum caption Matlock as “Little Switzerland,” or as a location with a “Switzerland view.” Copywriters in Southern England seized on the words of Romantic poet Robert Southey for the so-called Little or English Switzerland in Devon’s Lynton and Lynmouth. Of the latter, he wrote: “The beautiful little village, which I am assured by one who is familiar with Switzerland, resembles a Swiss village.” Evidently, Southey saw an Alpine likeness without ever having seen the real thing himself. Passed by word of mouth, these analogies became practically contagious and are still employed by the tourist industry today. After all, why else would a cable car dangle above the A6 in Matlock Bath, Derbyshire? Installed in the 1980s, this visitor attraction seeks to capitalize on the area’s Swissophilia, which dates back over two centuries.

Swiss Kitsch Everywhere

It was in this context that Swiss Gardens were dug and designed throughout England, both on private estates for the aristocracy and on land for attractions marketed to the public, centered on a stylized “Swiss Cottage.” Inspired by Rousseau’s novel Julie, Marie Antoinette had a little Swiss cottage built at Versailles in the 18th century, complete with cows and even a real-life dairy maid. The word chalet was borrowed into English from Swiss French, and by the mid-19th century, follies and cottages ornés were erected almost everywhere in a picturesque and only nominally Helvetian style, from the cosmopolitan centers and out into the provinces. London’s “Swiss Cottage” goes back to a pub built in 1804 in the Swiss chalet style. Extraordinary examples of Swiss Cottages can be found in Tipperary, Ireland, or at Endsleigh in Devon, England, which was designed around 1815 and is now rented out as holiday accommodation. In the Peak District, there is a village of Swiss chalets and a cottage-style schoolhouse in Illam, Staffordshire (near Dovedale), as well as a Swiss Cottage by a lake on the Chatsworth Estate built in 1842. The latter is also utilized for holiday amusement.

At first, all of these odd cottages looked similar—hardly quintessentially Swiss, but quaint for some visitors. However, in 1837, John Ruskin was scathing in The Poetry of Architecture, about “what modern architects erect, when they attempt to produce what is, by courtesy, called a Swiss cottage.” On aesthetic grounds, he wryly opposes “the modern building known in Britain by that name.” Ruskin is right insofar as the Swiss Chalet was appropriated by national architects. It differed across Europe but was generally consistent within regions. For example, in Norway, Swiss cottages were wooden structures, as most magnificently seen in the Hotel Union Øye, constructed in 1891, and the Kviknes Hotel, established in 1913. In England and among the Irish aristocracy, the fashion often signified a thatched building with an acutely gabled roof and usually bow windows, until even English Victorian terraced houses had “Swiss Cottage” etched into their brickwork. And in Britain, architectural Swissness soon became a name.

Besides architectural adaptations, Ruskin’s main objection was that the Swiss Cottage abroad had always been inauthentic and contrived, repeatedly describing its ornamental features derisively as “neat”; yet the structure aspires to be picturesque but fails. The idea does not work, he writes, observing that “the whole being surrounded by a garden full of flints, burnt bricks and cinders, with some water in the middle, and a fountain in the middle of it, which won’t play; accompanied by some goldfish, which won’t swim; and by two or three ducks, which will splash.” Although Ruskin had an airbrushed view of real life in the Alps, it is true that the Swiss cottages of England and elsewhere were fakes. But the foundation of Switzerland that they built upon in the popular consciousness was itself a fiction of authenticity. The literary and artistic image of a nation from the late 18th century has now been evoked for the 19th century in new Swiss stories of homesickness and an Alpine state, which, in the end, apparently offers the best of both educated and civilized, as well as sublimely natural worlds (Joanna Spyri’s Heidi was translated into English in 1882).

Such a stylized Swissness became increasingly fashionable over the late 19th century and moved ever further away from any plausible comparison to Switzerland or its fictions, which continued to influence public perception of the country. Around 1900, Swissophilia in England was at its height as ornaments at home and as local holiday amusements. For instance, on the implausibly flat place for the Alps called the Norfolk Broads, there were at least two “Little Switzerlands.” The names of these attractions seem to have signalled little other than neatly landscaped waterside parklands for public pleasure.

Ruskin would accuse the kitschy craze of Swiss cottages and Little Switzerlands at the foothills of modernity. Around 1800, Europe set mass consumer culture and increased commercial tourism in motion; once the train tracks were laid, more and more working- and middle-class day-trippers flocked to places such as Matlock from industrial cities like Manchester. Switzerland also became more accessible due to Thomas Cook’s tours, new railways, and cable cars. But Ruskin erred in seeing the antidote as authenticity and the genuine arts. We should remember that it was Wordsworth and his Romantic circle who first made the Alps less terrifying and remote for the British, and the foreign more familiar. Yet these authors were both participants in (and critics of) a nascent capitalist society and an emergent culture of European travel, which was briefly paused by the Napoleonic wars, with tropes packaged up and brought home. Given that these causal connections are complex, it suffices to say that the amusingly acerbic but simplistically anti-modern, pro-arts criticism of Ruskin doesn’t quite stand up to scrutiny.

Perhaps easier questions to pose are as follows: What was wrong, aesthetically speaking, with the conventional (if unauthentic)experience of Swissness in nineteenth-century England? Why criticize Swiss kitsch? The German philosopher Ludwig Giesz conceives of kitsch as not only, always, or even necessarily about a lack of authenticity. His list of kitschy characteristics from 1960 maps onto Little Switzerlands well because for him, kitsch is a sentimental idyll with pseudo- or vague ideals that feel real. It is about making the sublime insignificant and unthreatening. It renders the exotic everyday; the uncertain quotidian. There is no transcendence of the trivial. Such qualities may have been true for the experiences of Little Switzerlands in earlier centuries, but not nowadays. Swiss kitsch is problematic when compared to the original Switzerland, but not if we cease to perceive a relationship between Little Switzerlands and the actual Alps.

Reclaiming Curiosity

The Swiss Garden at Shuttleworth is one of the leading examples of the ornamental Swiss style, completed in the 1820s and 1830s and extending to the architecture of Old Warden, a village on the estate. The brainchild of Lord Robert Henley Ongley, the garden’s plans were explicitly influenced by handbooks such as J. B. Papworth’s Hints on Ornamental Gardening (1823). But this text did not yet illustrate a Swiss Cottage; instead, it focused on a “Polish Hut,” which was said to be “not unlike those of Switzerland.” It remains my speculation that Lord Ongley read the Romantics and followed a mainstream fashion for Switzerland in Regency England.

Although Ongley spent thousands of pounds on his picturesque project, contemporary visitor Emily Shore was unimpressed. In her July 23, 1835, journal entry, she wrote that the feature was “a very curious place”—a damning verdict that would surely have made Ruskin smile. For “the whole of this garden is in very bad taste, and much too artificial. The mounds and risings are not natural. . . . Even the Swiss cottage is ill imagined”.33 We can only guess how she would have perceived the Victorian additions of the industrialist John Shuttleworth, who, in the late 19th century, threw parties in this kitsch alpine playground (the era, incidentally, when the word “kitsch” was coined).

But as the years have passed, we have forgotten the original aesthetic aims of imagining English pastures or lawns as Little Switzerlands, or that such aspirations were turned into common attractions across the country—and, indeed, the continent and America (and in time, Australia, too). I think that the loss of context allows for a lighter, certainly less loaded appreciation of their strangeness in our contemporary landscape. We can look on, amused or bemused, at their foreignness amid the familiar. They appear to be not so much out of place as representative of no immediately comprehensible setting at all. Nowadays, the charm of a Little Switzerland is neither a lofty, aesthetic ideal of Romanticism, nor a conventional offer from the leisure industry. Wrenched from any referent that makes intuitive sense to us, today’s Little Switzerlands have become wonderfully weird.