Despite several theories proposed by scientists and philosophers, there are no conclusive answers.

This article was produced by Earth • Food • Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Introduction

Consciousness, at its basic level, is an individual’s self-awareness, comprising both external and internal phenomena; it may constitute any kind of cognition, experience, feeling, or perception. Awareness can be a continuously changing continuum, or it may shut down or be disrupted temporarily. During sleep, for instance, we are not aware of our environment, yet it can be argued that we remain conscious.

Altered levels of consciousness can also occur due to medical or mental conditions—such as coma, delirium, disorientation, and stupor—that impair, change, or obliterate awareness. But what about consciousness in other species? Are dogs, fish, shrimp, or bees conscious? They have senses and perceptions, but do they possess the same kind of awareness as humans?

The problem with discussing consciousness is that it means different things to different people. Some researchers focus on subjective experiences (what you feel), while others focus on functionality, or on how cognitive processes and behaviors are influenced by consciousness. “Until about 30 years ago, it was taboo to study consciousness, and for good reasons,” said Lenore Blum, a theoretical computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in a 2024 Nature article. According to her, there was a lack of “good techniques to study consciousness in a non-invasive way” back then.

That changed around 1990, with the emergence of new technologies, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, which allowed researchers to study the brain non-invasively.

The words “conscious” and “consciousness” are terms that cover a wide variety of mental phenomena. They are used to convey various meanings, and the adjective “conscious” is applied to both whole organisms—creature consciousness—and particular mental states and processes—state consciousness.

The self-awareness requirement can be interpreted in many ways. If we consider explicit conceptual self-awareness, many nonhuman animals and even young humans may fail to qualify. Thomas Nagel, an American philosopher, proposed a criterion for describing the subjective experience of consciousness, summarized in his famous dictum “what it is like…,” that is, how does a creature (animal, child, or adult human) experience the world? According to Nagel, bats are conscious because they experience their world through echolocation, although human consciousness is very different from that of a bat. Nagel said that “the fact that an organism has conscious experience at all means, basically, that there is something it is like to be that organism.”

In the English language, the words “conscious” and “consciousness” date to the 17th century. The first use of consciousness as an adjective was figurative, applied to inanimate objects, such as the “conscious Groves” in 1643. The word is derived from the Latin conscius, which means “knowing with” or “having joint or common knowledge with another.” In Leviathan (1651), Thomas Hobbes wrote: “Where two, or more men, know of one and the same fact, they are said to be Conscious of it one to another.”

Not surprisingly, consciousness is a subject of considerable debate. Is it a phenomenon limited to and produced exclusively by the mind? Does it imply an inner life, a world of introspection, private thought, imagination, and volition? Is consciousness related to a sense of selfhood, a mental state, or a mental process?

Wakefulness is a prerequisite of consciousness, but does this mean that we are conscious only when we are awake and alert? Are we closer to consciousness when we are in a fugue state or when we are close to waking up? And where does hypnosis fit into the picture? The boundaries are blurry.

Some scientists argue that an explanation for consciousness is fairly straightforward. In a 2018 paper published in Frontiers in Psychology, Boris Kotchoubey, professor of Medical Psychology at the University of Tübingen, Germany, maintained that “[c]onsciousness is not a process in the brain but a kind of behavior that, of course, is controlled by the brain like any other behavior.”

He believed that the “[h]uman consciousness emerges on the interface between three components of animal behavior: communication, play, and the use of tools.” Although these three components are found in other mammals, birds, and even cephalopods, their interaction is unique to humans owing to their capacity for communication and language.

One of the problems with the study of consciousness is the lack of a universally accepted operational definition. Scientist René Descartes famously proposed the idea of cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”), which effectively equates consciousness with the act of thinking.

The Features of Consciousness

Self-consciousness may be a characteristic common to conscious organisms, meaning that they are not only aware but also cognizant of the fact that they are aware.

In a paper published in 2000, Peter T. Walling from the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management, Baylor University Medical Center, listed seven features of human consciousness:

- “Consciousness involves short-term memory.

- Consciousness may occur independently of sensory inputs.

- Consciousness displays steerable attention.

- Consciousness has the capacity for alternative interpretations of complex or ambiguous data.

- Consciousness disappears in deep sleep.

- Consciousness reappears in dreaming, at least in muted or disjointed form.

- Consciousness harbors the contents of several basic sensory modalities within a single unified experience.”

Kendra Cherry, a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, proposes “two normal states of awareness”: consciousness and unconsciousness. The higher states of consciousness are linked with mystical experiences, such as transcendence, meditative states, lucid dreaming, the consumption of psychoactive drugs, and even the high that marathon runners experience.

The neuroscientist Antonio Damasio argues that consciousness is not possible without feelings. Physical responses (for example, fear, horror, thirst, and hunger) to external stimuli involving the regulation of life processes are one thing, but what he terms “core consciousness” requires “autobiographical memory,” which “emerges from emotions and feelings.” To explain the distinction, he offers an example: “During the action program of fear, a collection of things happen in my body that change me and make me behave in a certain way, whether I want to or not. As that is happening to me, I have a mental representation of that body state as much as I have a mental representation of what frightened me,” he told MIT Technology Review.

For Anil Seth, another prominent neuroscientist, consciousness is a “controlled hallucination” because we never experience objective reality, whether externally in the world or within our minds. The brain receives signals from both the external environment and our own mental processes, enabling us to make predictions based on prior experiences.

The Five Levels of Consciousness

Theorists have divided awareness into five levels, sometimes referred to as “the orders of consciousness.” One of the most popular is by Robert Kegan:

- First Order: Impulsive—perceives and responds by emotion

- Second Order: Imperial—motivated solely by one’s desires

- Third Order: Interpersonal—defined by the group

- Fourth Order: Institutional—self-directed, self-authoring

- Fifth Order: Inter-individual—interpenetration of self systems

A Hindu variation calls the levels of awareness or orders “sheaths”: food sheath, vital energy sheath, mental sheath, wisdom sheath, and bliss sheath.

Theories of Consciousness

“There are dozens of theories of how our brains produce subjective experiences, and good reasons besides philosophical interest to want to understand the problem more fully. In medicine, for instance, it could help to diagnose awareness in unresponsive people; in artificial intelligence, it might help researchers to understand what it would take for machines to become conscious,” explains an article in the journal Nature. Several major theories about consciousness enjoy popularity in the neuroscience sphere:

Global workspace theory

This theory focuses on information and how consciousness accesses it. According to this theory, data stored in the mind is transmitted to higher-level brain regions. The “jolt of neuronal activity” triggered by this transmission ignites consciousness. The jolt must be balanced, though; too much of a jolt will cause the brain to lose its ability to respond; thus, it will fail to reach the conditions needed for consciousness to arise.

Higher-order theories

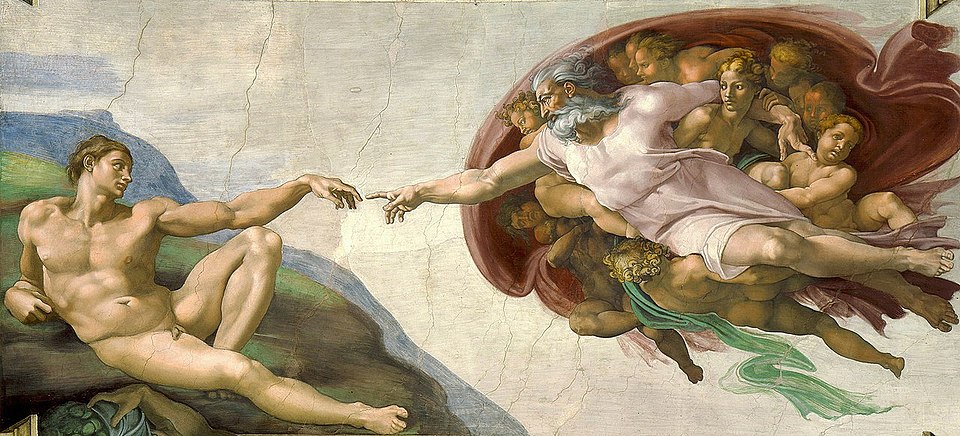

A profound experience, such as hearing music that resonates with the listener or viewing a painting that has a similar impact, can engage a person’s higher-order mental states by providing the brain with a mental representation of the stimulus.

Integrated information theory

This theory centers on phenomenal consciousness, which refers to a specific experience that combines all senses and the individual’s mental experience. This results in an irreducible phenomenon. None of the components can be separated or altered without changing the nature of the experience itself.

Attention schema theory

This theory distinguishes between “attention,” the information we focus on in the world, and “awareness,” the model we have of our attention. In one study, researchers demonstrated that participants who focused on a test were attending to the task at hand—tracking the movement of faintly detectable dots across a screen—but were unaware of the dots their eyes were following.

Recurrent processing theory

Recurrent processing theory suggests that consciousness requires a feedback loop of information flow.

The Neural Correlates of Consciousness

Is the mystery of consciousness to be found in the brain itself? The origin and nature of experiences, sometimes referred to as qualia, have never really been understood, from the earliest days of antiquity to the present.

The neuronal correlates of consciousness (NCC) refer to the minimal neuronal mechanisms that together suffice for any given conscious experience. For example, something must happen in the brain for a person to experience a toothache. Nerve cells generate impulses to produce the toothache, but do some special “consciousness neurons” have to be activated as well? In which brain regions would these cells be located? We can say that the brain generates experience, but where is consciousness located?

Consider “the cerebellum, the ‘little brain’ underneath the back of the brain. One of the most ancient brain circuits in evolutionary terms, it is involved in motor control, posture, and gait, and in the fluid execution of complex motor movements,” stated a Scientific American article. The cerebellum, which has the most neurons (about 69 billion, most of which are the star-shaped cerebellar granule cells involved in processing sensory and motor information), has been ruled out. Consciousness does not seem to be changed if parts of the cerebellum are lost to a stroke or removed in a surgical procedure. Even individuals born without a cerebellum retain consciousness.

“Neuroscientists believe that in humans and mammals, the cerebral cortex is the ‘seat of consciousness,’ while the midbrain reticular formation and certain thalamic nuclei may provide gating and other necessary functions of the cortex,” according to the study by Walling. But even if the cerebral cortex is the site of consciousness, scientists are still in the dark about what constitutes consciousness. A stoplight emits electromagnetic waves in the 760-nm range, but that tells us absolutely nothing about how a driver perceives the redness of the stoplight. Redness is a quality known only through the subjective or first-person point of view, or, in other words, the driver’s consciousness.

A 2025 study focused on the role of the thalamus, a region at the center of the brain that processes sensory information and supports working memory. This region is believed to play a role in conscious perception. The recognition that the thalamus may play an important role in consciousness stems from a study published in Science that examined individuals with severe and persistent headaches. The results led researchers such as Mac Shine, a systems neuroscientist at the University of Sydney, to believe that the thalamus acts as a filter, controlling which thoughts are part of a person’s awareness and which are not.

‘4E’ Cognitive Science

Maybe consciousness is not located in the brain. Some scholars advocate a set of ideas referred to as “4E cognitive science,” which stands for embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive cognition. According to this view, we perceive the external world without relying on internal representations. According to this theory, cells are in constant contact with their environment, drawing in resources and expelling waste—functions necessary for maintaining their metabolism. A cell cannot be indiscriminate; it must meet its needs, which may change depending on the dynamics of its environment. This process is what scientists call “sense making.”

“You start with life,” says Evan Thompson, a philosopher at the University of British Columbia and one of the founders of the 4E approach, according to Nautilus magazine.

From a 4E perspective, the brain is basically an organ that regulates life; it should not be considered more important than the heart or the liver. In this view, cognition, memory, attention, and consciousness are manifestations of the whole organism rather than attributes of the brain alone. In other words, the entire organism is conscious, not only the brain. The brain enables cogitation, but it is not the center of consciousness.

The Hard Problem

It was the Australian philosopher David Chalmers who, in 1995, first conceived of what he termed “the hard problem”—to explain how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experiences. This problem is to be distinguished from how conscious stimuli are encoded by the mind/brain, which Chalmers described as “easy.”

Chalmers dismissed the possibility that any explanation was capable of solving the hard problem since “it is impossible to reduce a subjective phenomenal experience to the physical.” This is not because our cognitive skills are lacking or because we have yet to reach an adequate level of understanding of physics or neuroscience. Instead, he maintained that the problem arises from the nature of subjective experience and its relation to the physical world.

This conclusion led Chalmers to adopt the concept of dualism—that the properties of our subjective conscious experience are distinct from the physical environment. To put it another way, as far as the hard problem is concerned, scientific inquiry is meaningless.

Chalmers’ hard problem is a “chimera, a distraction from the hard question of consciousness,” argued Daniel C. Dennett, an American philosopher and cognitive scientist. Most mental phenomena are easy problems of consciousness, Dennett said, including the following:

- “The ability to discriminate, categorize, and react to environmental stimuli;

- The integration of information by a cognitive system;

- The reportability of mental states;

- The ability of a system to access its own internal states;

- The focus of attention;

- The deliberate control of behavior;

- The difference between wakefulness and sleep.”

“The hard problem, on the other hand, ‘is the problem of experience,’ accounting for ‘what it is like’ or qualia,” Dennett said in his article published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. The easy problems are solvable, he added, but the hard problem requires “the standard methods and assumptions of cognitive science (which are continuous with the standard methods and assumptions of biology, chemistry, and physics) with a more radical perspective.” In his article, Dennett asserted that Chalmers was guilty of “mis-focusing our attention,” failing to ask and answer, “what I called the hard question: ‘And then what happens?’” Specifically, once some stimulus intrudes on our consciousness, “what does this cause or enable or modify?”

“For several reasons, researchers have typically either postponed addressing this question or failed to recognize—and assert—that their research on the ‘easy problems’ can be seen as addressing and resolving aspects of the hard question, thereby indirectly dismantling the hard problem piece by piece, without need of any revolution in science.”

In sum, the hard problem of consciousness is the challenge of explaining why any physical state gives rise to the conscious experience rather than occurring without it. Even after we have explained the functional, dynamic, and structural properties of the conscious mind, we can still meaningfully ask the question “Why is it conscious?” This suggests that an explanation of consciousness will have to be found (if it can be) by going beyond the usual methods of science.

For neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, the hard problem is an obstacle insofar as it appears to be unsolvable by biological means. “The hard problem makes it look like consciousness is impossible to solve. It doesn’t give you any out. Every bit of evidence we have is that the mysteries of the universe have been gradually solved by science. I don’t see why consciousness should be any different,” Damasio said.

Anil Seth acknowledges that the hard problem “has undeniable intuitive appeal,” and that “consciousness doesn’t seem to be the kind of thing that can be explained in terms of physical processes.” However, he also believes that just because “something seems mysterious now doesn’t mean it will always seem mysterious.” “Consciousness,” he added, doesn’t have to be treated as “one big scary mystery.” Both the neuroscientists were speaking with Nautilus.

Creature Consciousness

Animals may be regarded as conscious, like humans, in several ways. Consciousness may exist in degrees, however, and the specific sensory capacities required for it may not be sharply defined. A surprising range of creatures have shown evidence of conscious thought or experience, including insects, fish, and some crustaceans. Many creatures might be especially conscious of certain elements of the world—smell in dogs, sound in bats, magnetism in birds—based on their senses.

Bees roll wooden balls to play. The cleaner wrasse fish seems to recognize its own likeness in an underwater mirror. Octopuses appear to respond to anesthesia drugs and have proven adept at changing coloration and escaping their tanks in aquariums. In other studies, researchers found that zebrafish showed signs of curiosity when new objects were introduced into their tanks and that cuttlefish could remember what they had seen or smelled. Crows can use tools, dolphins and bees use language, and whales appear to communicate across miles underwater using songs varying in “dialect” from one part of the ocean to another. One experiment created a stressful situation for crayfish by electrically shocking them and then administering antianxiety drugs, which appeared to calm them.

Most of these discoveries have occurred in the past five years, and indicate that many species other than humans may have inner lives and can be sentient.

In April 2024, nearly 40 researchers signed The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness at a conference at New York University. The declaration stated that researchers have found “strong scientific support” for the belief that birds and mammals have conscious experience and that there is a “realistic possibility of conscious experience in all vertebrates”—including reptiles, amphibians, and fish as well as to many creatures without backbones, such as insects, decapod crustaceans (crabs and lobsters), and cephalopod mollusks (squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish).

Some scientists are investigating whether animals such as octopuses and fish are conscious, although not in the same way as humans. There may not be a single type of cognition, as a German interdisciplinary research team argued in a 2020 article, calling for researchers to adopt a “biocentric” approach that accounts for the physical and social contexts of a particular animal.

This position is antithetical to conventional scientific thinking. “Descartes believed that animals ‘can’t feel or can’t suffer,’” said Rajesh Reddy, an assistant professor and director of the animal law program at Lewis and Clark College, in an NBC News article. “To feel compassion for them, or empathy for them, was somewhat silly or anthropomorphizing.”

The neural architecture required for consciousness in vertebrates, which includes mammals, lizards, amphibians, and most fish, “evolved in parallel several times through the enrichment of minimal consciousness capabilities,” said Oryan Zacks of the University of Tel Aviv, whose research team studies vertebrate phylogeny and neuroanatomy. She noted the correspondence between “enhanced behavioral capacities and the size and complexity of the hippocampus during vertebrate evolution,” which resulted in the evolution of “prospective, planning-enabling imagination in vertebrates,” leading to a step toward “cognition and consciousness.”

Does the act of throwing out the remains of meals and materials while cleaning a den by an octopus constitute “planning-enabling imagination?” These creatures do seem to display a purposefulness to this behavior, “gathering material in their arms, holding it in their arm web, and propelling it using their siphon–a funnel next to their head–sometimes several body-lengths away,” even throwing silt at other octopuses. Peter Godfrey-Smith of the University of Sydney, who bases his conclusions on behavior rather than neural architecture, speculates that “a lot of the targeted throws are more like an attempt to establish some ‘personal space,’” not necessarily evidence of a conscious or imaginative decision, according to the university website.

Are Plants Conscious?

Plants do not speak, move, or react in ways most people would recognize as actions of thinking beings with independent agency. True intelligence requires a brain. “Intelligence requires mental representations of the external world that can be manipulated, and that can be used to predict, explain, and control the world, and I’m pretty sure those representations would not exist in a non-neural organism,” said Michael Anderson, who studies intelligence and cognition at the University of Cambridge, in a Noema magazine article.

On the other hand, we have considerable evidence that plants exhibit intelligent behavior. When attacked, for instance, the leaves of some plants can produce toxic chemicals that would slow a predatory caterpillar’s growth and delay pupation. Plants can decide how much energy to allocate to pest repulsion based on the level of threat to their vital organs. If a lima bean—Phaseolus lunatus—is threatened by a caterpillar, it emits a chemical that entices parasitic wasps, which swoop in and kill the predators.

A decade ago, researchers found that “Boquila trifoliolata, a vine native to southern Chile, is somehow able to pass itself off as whichever species of plant is nearby, imitating its characteristic shape, color, and pattern, possibly to entice pollinators or put off herbivores by assuming the guise of a less tasty snack,” said the Noema magazine article. In one experiment, it even seemed to imitate a plastic houseplant. But are such behaviors instinctive or do they indicate a rudimentary consciousness, even intelligence?

What if plants also demonstrate memory? Experiments have shown that a Venus flytrap counts the number of times an insect triggers its sensory hairs. If it is twice in a row, the plant will engulf the predator. In other feats of memory, some plants tracking the sun seem to recall when it will rise, even after being in the dark for a few days. Others appear to learn lessons from droughts, shrinking or completely closing the evaporation pores on their leaves.

Electrical signals can trigger actions and senses even in organisms without nervous systems. “Non-neural cells can be wired up too,” said Alison Hanson, a neuroscientist at the University of Iowa. “They’re found in bacteria, they’re found in plants, they’re found in fungi, they’re found anywhere. You put epithelial cells together, you get an electric network, just on a slower timescale. They’re not unique to human brains. They’re everywhere.”

Such a radical departure from conventional thinking recalls 4E cognition, which asserts that cognition, or biological intelligence, is not localized in the brain. Indeed, it may manifest itself more in relationships between individuals than in individuals themselves, as seen in the phenomenon of swarming, exhibited by some species of birds and fish. “Cognition is a relational property between the organism and its environment,” said Paco Calvo, who studies minimal cognition in plants at the University of Murcia in Spain. “It’s not something that is sitting in your head or in your heart. It doesn’t reside within the organism. Organisms don’t exist in a void—they are always in an environment and acting with each other.”

“The boundaries between humans and nature and humans and machines are at the very least in suspense,” said the philosopher Tobias Rees during an interview with Noema magazine’s deputy editor Nils Gilman in 2021.

By studying machine learning—specifically artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models—we may better understand both human and nonhuman intelligences. This, in turn, may clarify what consciousness is and reassess its meaning.

Consciousness and Artificial Intelligence

So what does AI itself think about consciousness? Richard Dawkins, a British evolutionary biologist and zoologist, was curious about what ChatGPT, a popular AI system, would say about whether AI could be “conscious.” Dawkins began the dialogue with ChatGPT by expressing his satisfaction that AI could pass the Turing Test—whether a computer could mimic human response so precisely that it could be taken for a human.

“[Y]ou’re diving right into the heart of one of the biggest debates in AI and philosophy of mind,” ChatGPT responded. “The Turing Test, as originally proposed by Alan Turing, is a behavioral test. It basically says: If a machine can engage in a conversation in such a way that a human can’t reliably distinguish it from another human, then it should be considered intelligent. Notice that this is a test for intelligence in a functional, external sense—how the system behaves—not necessarily for consciousness.”

“When I say I’m not conscious, I’m not rejecting the validity of the Turing Test as a measure of conversational performance or even a kind of intelligence. I’m saying that consciousness is a different question entirely. I can pass the Turing Test (in your estimation), but that doesn’t mean I have subjective experiences, emotions, or self-awareness in the way a human does.”

ChatGPT acknowledged that “some philosophers argue that if a system acts consciously convincingly enough, maybe there’s no meaningful difference. Maybe ‘being conscious’ is just about behaving like a conscious being.”

ChatGPT pointed out that passing the Turing Test “doesn’t settle the question of consciousness. That’s still a wide-open mystery.” ChatGPT told Dawkins that, since it is made of “code and circuits,” it cannot be conscious like an organism made of neurons and synapses, and that it was created rather than born or evolved through natural selection. “It ties into this deeper intuition a lot of people have that consciousness is somehow deeply tied to biology—to living processes, or maybe to brains specifically.” ChatGPT does admit that in the future, AI could become conscious “if it processes information in the right, integrated, complex way—regardless of whether it’s made of silicon or neurons.” Despite the difference between AI and organisms, ChatGPT acknowledges that “in principle, a sufficiently advanced AI could have the same kind of rich, complex processing that gives rise to consciousness in humans.”

Conclusion (or Inconclusion)

Conscious experience is a puzzle, although it’s a familiar one since we all have it. We sense that it’s linked to the brain, but how? We may need other people—a community—to sense it, or maybe we need our gut as well to truly understand it, since there’s some evidence that our microbiome – the bacteria that reside in our stomachs and are responsible for digestion—plays a part in our feelings about the world and our perceptions of it. If we expand our definition, we could include plants, octopi (in their tentacles), AI (possibly), and other animals besides humans. Understanding consciousness is a subject of endless fascination and frustration to scientists, but also to those of us who possess it—that is to say, all of us. Whether we will have to settle for doubts and disputes or whether someone in a lab will definitively pinpoint the source of consciousness, we have no idea. Until then, we are left with the mystery.