Survival of the Cutest

The appearance of cuteness is not arbitrary, but rather an evolutionary mechanism that promotes infant and group survival.

The human response to “cuteness” is immediate and seemingly universal, transcending cultural boundaries. Across the globe, people generally agree that small puppies, lion cubs, and other juvenile animals evoke feelings of warmth, affection, and positive emotions. In fact, the initial reaction on seeing infants is to smile.[1] Though we can easily identify what we consider “cute,” it is harder to explain this emotional reaction. Why do we respond this way?

The perception of cuteness is rooted in behaviors and preferences that promote survival, social bonding, and caregiving. While individual taste and social conditioning play a role, perceptions of cuteness tap into our neural network to promote caregiving behavior, especially toward vulnerable human infants.

The Anatomy of Cute

Though often described in subjective terms, there is a set of physical and behavioral traits that generally elicit the response that something is cute. These same traits have been reliably shown to trigger nurturing responses in people.

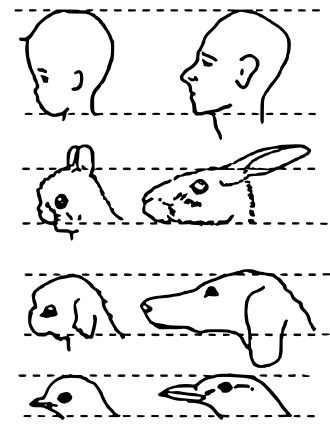

Austrian ethologist Konrad Lorenz first proposed the concept of “Kindchenschema,” or “baby schema,” in 1943. In essence, the term describes the schematic of human infants and a set of typical features that include a large head-to-body ratio, a small nose and mouth, disproportionately large eyes, a round face, a protruding forehead, and stubby extremities. These features, also described as neotenous, appear in many juvenile animals, making them appealing to us across species.

“Lorenz posited that our brain’s response to cuteness is an evolutionary adaptation: Cuteness triggers innate caregiving, nurturing, and protective behavior to improve the likelihood of species survival. He believed our response to cuteness was irrepressible,” states a 2024 National Geographic article.

In 2012, researchers Melanie Glocker, Daniel Langleben, and others experimentally tested the effects of baby schema on the perception of cuteness and caregiving attention. After digitally editing photographs of infants to exaggerate specific facial features associated with baby schema, the researchers asked participants to rate the photos based on cuteness. The infants with high baby schema features were consistently rated as cuter and evoked stronger caregiving motivation, providing the first experimental evidence that Kindchenschema proportions directly influence caretaking behavior and supporting its role in human social cognition.[2]

Evolutionary psychologist Daniel J. Kruger also tested people’s responses to different types of animal infants in 2015. Some animal species are semi-precocial, requiring care, while others are super-precocial and are more independent and need less parental care. When presented with images of baby animals from both types of species, participants rated the more dependent, semi-precocial animals as cuter than their independent counterparts, regardless of whether the species were mammalian or not.

The Role of Cute

Across all species, infancy is a crucial period for an individual’s success. This is especially true for human infants, who require years of investment from the adults around them before they can become somewhat independent, while other species’ young can walk and search for food at an early age. In addition, humans produce fewer offspring, who are more “expensive” to birth and raise in terms of resources. Since human infant mortality and childhood death rates were high throughout all periods of prehistory, our behavior and morphology likely adapted to this selective pressure.[3]

“Child death appears to be a strong pre-reproductive universal pressure in human evolution. As such, it has likely exerted a strong influence on the evolution of the human mind,” states a 2008 study published in the Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology.

When an infant is considered “cute,” it is more likely to receive greater parental investment, which includes protection and care from their biological parents and beyond. People tend to look at cute infants for longer periods, and mothers of cuter children tend to be more affectionate toward them. In addition, cute infants are perceived as healthier and more competent, and more adoptable than those considered less cute.[4]

In early human communities, cooperative caregiving by adults aside from a child’s parents played a significant role in the survival of that child. Members of the same community, whether extended family or other individuals, sometimes partake in the care of offspring through a behavior known as alloparenting. According to the cooperative breeding hypothesis, anthropological research suggests that these types of allomaternal or allopaternal relations were crucial for child survival during the Pleistocene.[5] “This breeding system—quite novel for an ape—permitted hominid females to produce costly offspring without increasing inter-birth intervals, and allowed humans to move into new habitats, eventually expanding out of Africa,” according to a 2006 study published in the journal Family Relations.

Taking care of someone else’s children might seem counterintuitive, as it would take energy and resources away from one’s own genetic success. In reality, however, this behavior increases the survival of distantly related kin and strengthens group cohesion. Investment of parental care from a wider network of caretakers thus enhances the survival of both individuals and the community as a whole.

The Neuroscience of Cute

Stephen Hamann, a psychology professor at Emory University, found that cuteness increases brain activity, particularly in the orbital frontal cortex and the amygdala. Activity within the orbital frontal cortex, associated with decision-making, and the amygdala, associated with emotional regulation, became especially pronounced when participants looked at images with neotenous features. In terms of the emotional response, cuteness can help trigger empathy and compassion in individuals.

Two experiments tested the behavioral response to cuteness. In a 2009 study published in the journal Emotion, researchers Gary D. Sherman, Jonathan Haidt, and James Coan examined the behavioral implications of viewing cute animals on carefulness in humans. They found that participants who viewed pictures of puppies and kittens performed significantly better on a task that requires fine-motor dexterity—in this case, a game of Operation–than those who viewed photos of adult dogs and cats. The researchers’ second experiment confirmed that perceived cuteness enhances carefulness.[6]

Cuteness not only triggers emotional caregiving impulses but also prepares the body for more precise movements and physical interactions, perhaps as an adaptation for handling fragile infants.

Cuteness Today

Evolutionary biologists believe that cuteness has also influenced the development of certain traits in the animals we live with. “Puppy dog eyes,” for example, are seen in domestic dogs but not in wild wolves. Human-like expressions in dogs have been “consciously or unconsciously favored and therefore selected” by us for approximately 33,000 years. Due to a slow transformation in facial anatomy, domesticated dogs now have an eyebrow levator muscle responsible for the “sorrowful” expression we see today.[7]

Cuteness likely evolved as a mechanism to promote infant care, strengthen social bonds between group members, and attract human affection. As a result, we enjoy looking at cute infants and animals. Plush toys, “cat-like” cartoon characters, and other designs often incorporate baby schema features to evoke consumer interest, harnessing the aesthetics of cuteness as a marketing tool.

Caregivers can perceive their infant as less cute in certain instances, such as when a visible physical condition is present. This may reduce emotional investment on the parents’ end and negatively affect the child’s development.[8] Further research on cuteness can help us understand these types of issues that arise in parent-child bonding and aid researchers in developing early interventions to enhance caregiver responsiveness. Ultimately, understanding the influence of “cute” may help us become more conscious caregivers and more empathetic members of society.

- ↑ M. Schleidt, W. Schiefenhővel, K. Stanjek, and R. Krell (1980). “‘Caring for a Baby’Behavior: Reactions of Passersby to a Mother and Baby.” Man-Environment Systems. Vol. 10, Issue 2, pp. 73–82.

- ↑ Melanie L. Glocker, Daniel D. Langleben, Kosha Ruparel, James W. Loughead, Ruben C. Gur, and Norbert Sachser (2009). “Baby Schema in Infant Faces Induces Cuteness Perception and Motivation for Caretaking in Adults.” Ethology. Vol. 115, Issue 3, pp. 257–263.

- ↑ Tony Volk and Jeremy Atkinson (2008). “Is Child Death the Crucible of Human Evolution?” Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology. Vol. 2, Issue 4, pp. 247–260.

- ↑ S.F. Chin, T.J. Wade, and K. French (2006). “Race and Facial Attractiveness: Individual Differences in Perceived Adoptability of Children.” Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology. Vol. 4, Issue 3–4, pp. 215–229.

- ↑ Sarah Blaffer Hrdy (2006). “Evolutionary Context of Human Development: The Cooperative Breeding Model.” C.S. Carter, L. Ahnert, K.E. Grossmann, S.B. Hrdy, M.E. Lamb, S.W. Porges, and N. Sachser (eds.), In Attachment and Bonding: A New Synthesis (MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2005), pp. 9–32.

- ↑ Gary D. Sherman, Jonathan Haidt, and James Coan (2009). “Viewing Cute Images Increases Behavioral Carefulness.” Emotion. Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 282–286.

- ↑ Juliane Kaminski, Bridget M. Waller, Rui Diogo, Adam Hartstone-Rose, and Anne M. Burrows (2019). “Evolution of Facial Muscle Anatomy in Dogs.” PNAS. Vol. 116, Issue 29.

- ↑ Christine E. Parsons, Katherine S. Young, Emma Parsons, Annika Dean, Lynne Murray, Tim Goodacre, Louise Dalton, Alan Stein, and Morten L. Kringelbach (2011). “The Effect of Cleft Lip on Adults’ Responses to Faces: Cross-Species Findings.” PLOS One. Vol. 6, Issue 10.