The Super Predator: How Humans Became the Animal Kingdom’s Most Feared Hunters

Humanity’s evolution into a super predator has reshaped ecosystems and instilled a primal fear in much of the animal kingdom.

Hunting is considered critical to human evolution by many researchers who believe that several characteristics that distinguish humans from our closest living relatives, the apes, may have partly resulted from our adaptation to hunting, including our large brain size.

Over time, however, the need to hunt for survival has been replaced by greed, leading to the exploitation of natural resources, which is destroying the environment and causing the extinction of thousands of species.

There has been a 60 percent decrease in the wildlife population between 1970 and 2014, according to the Living Planet 2018 report by the World Wildlife Fund. Referring to the report, the Guardian stated that “the vast and growing consumption of food and resources by the global population is destroying the web of life, billions of years in the making, upon which human society ultimately depends for clean air, water and everything else.”

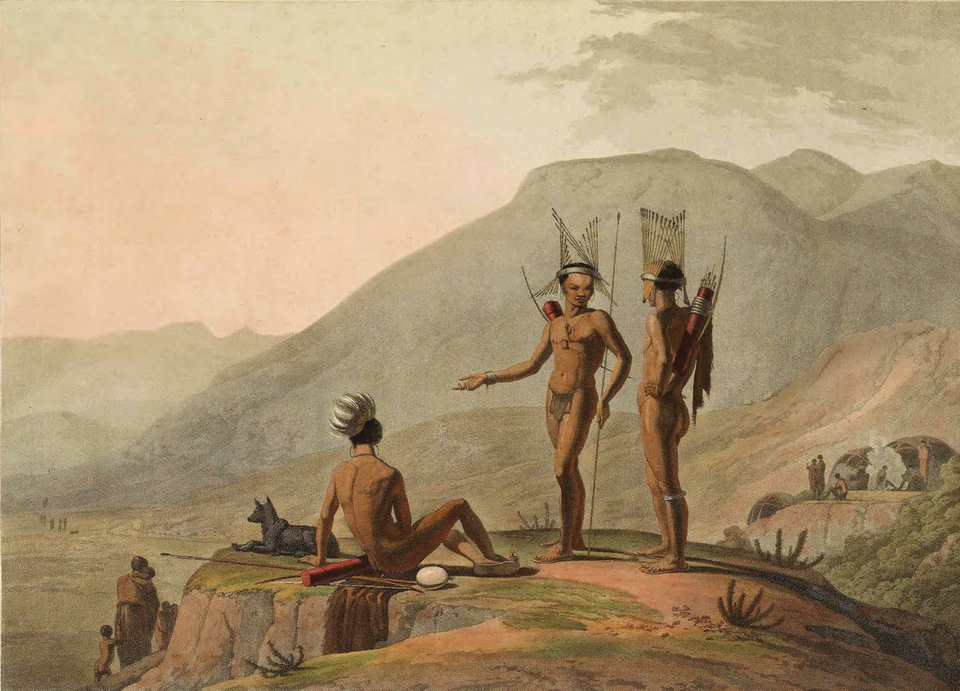

Hunting for Survival

The San People, also known as the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert in Africa, have for generations employed persistence or endurance hunting to chase down prey such as the kudu. Groups of three or more men find a herd and scatter it, targeting the weakest, slowest, or heaviest animal in the herd. During the hunt, one of the Bushmen serves as the main runner, who finishes the last legs of the hunt by tracking and finally killing the prey. Although the Bushmen do employ more familiar tactics like ambushing, shooting poisoned darts, and throwing spears, persistence hunting has been a standby of the San People in an environment that favors human endurance and stamina.

Over the years, however, persistence hunting has become a topic of debate. In a 2007 article published in the Journal of Human Evolution, Henry T. Bunn, a paleoanthropologist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Travis Rayne Pickering, a professor of anthropology from UW-Madison, questioned the assumption that endurance training was “regularly employed” during hunting and scavenging. They argued that humans would have relied more on their brains than their legs to hunt.

Bunn and Pickering studied a pile of bones found in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, dating back to 1.8 million to 2 million years ago—which were unearthed by paleontologist Mary Leakey—and discovered that “most of the animals in the collection were either young adults or adults in their prime… To Bunn and Pickering, that suggested the animals hadn’t been chased down. And because there were butchering marks on the bones with the best meat, it was also safe to assume that humans hadn’t scavenged animal carcasses after being killed by other predators… Instead, Bunn believes ancient human hunters relied more on smarts than on persistence to capture their prey,” according to a 2019 article in Undark magazine.

Opposing this debate are researchers such as Eugène Morin, an evolutionary anthropologist at Trent University in Canada, and Bruce Winterhalder, from the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate Group in Ecology at the University of California, Davis. A 2024 article written by them, published in the journal Nature Human Behavior, revealed that they scoured ethnographic records and identified almost 400 cases of long-distance running used for hunting around the world. Their research on energy expenditure shows that “running can be more efficient than walking for pursuing prey,” stated a Smithsonian magazine article.

Many other scholars have written about the “locomotor endurance” that humans possess compared to other animals, as well as the anatomical advantages of long legs, Achilles tendons, arched feet, and large, stress-bearing joints in our legs, which collectively contribute to our ability to run long distances.

Whether humans originally evolved as persistence hunters is a matter of debate. What is undeniable is that humans are among the most deadly predators on Earth. “From agricultural feed to medicine to the pet trade, modern society exploits wild animals in a way that surpasses even the most voracious, unfussy wild predator,” said a Smithsonian magazine article.

Ways to Kill

A 2023 study, “Humanity’s Diverse Predatory Niche and Its Ecological Consequences,” published in Communications Biology, describes human predation as a commercial enterprise rather than a necessity:

We consider predation by humans broadly—and from the perspective of effects on prey populations—as any use that removes individuals from wild populations, lethally or otherwise… [ranging] from removal of live individuals for the pet trade, to harvesting by societies that rely heavily on hunting and fishing, to globalized, commercial fishing and trade of vertebrates, and interactions among these activities.

When a shark, a tiger, a boa constrictor, or even the rusty-spotted cat of South Asia kills another animal, its primary aim is survival. As carnivores, these animals must eat meat, and therefore, they must kill. But humans go beyond the necessary. In our years of remodeling landscapes and industrializing the wilderness, we have pushed animals toward extinction. Our activities have had maximum impact on the ocean, leading to the exploitation of 43 percent of Earth’s marine species. While these species are killed for several purposes, 72 percent of marine and freshwater fish species are being used for food. Taxonomically, birds were the most predated group, with 46 percent mainly being used as pets or for other “recreational pursuits.”

Meanwhile, “in the terrestrial realm, use as pets is almost twice as common (74 percent) as food use (39 percent),” according to the 2023 study. Sport hunting and other forms of activities (i.e., for trophies) accounted for 8 percent of the use of exploited terrestrial species.

Due to humanity’s alarming exploitation of 14,663 species, we are driving 39 percent of these species toward extinction. “We exploit around a third of all wild animals for food, medicines, or to keep as pets… That makes us hundreds of times more dangerous than natural predators such as the great white shark,” according to a 2023 BBC article, referring to an analysis by scientists. The article further stated that we were entering the Anthropocene, “the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.”

Today, human-induced climate crises and environmental damage are the forces that pulverize bones to dust. An analysis of peer-reviewed literature published between 2012 and 2020 revealed 99 percent consensus that human activity shapes climate change—a collective power that no other species on Earth has ever had. Not even the dinosaurs would have been able to out-roar the din of factories and exhaust pipes.

Fearful Symmetry

Human beings have been termed “super predators,” surpassing other famous predators in the number of prey they kill. This has led to animals fearing us. “Consistent with humanity’s unique lethality, a growing number of playback experiments have demonstrated that fear of humans far exceeds that of the non-human apex predator in the system. In Africa, 95 percent of carnivore and ungulate species (e.g., giraffes, leopards, hyenas, zebras, rhinos, and elephants) in the Greater Kruger National Park ran more or faster on hearing humans compared with hearing lions,” stated the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences.

An atavistic fear also afflicts animals when they see a human. We might be slower and weaker creatures compared to bears and lions, but to these animals, we look monstrous. “There is a threat level that comes from being bipedal,” said John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, to Live Science. So when, say, a kudu in the Kalahari Desert spots one of the San People or Bushmen jogging or walking toward it, the kudu bolts.

This ecology of fear has shifted the predator-prey paradigms, as ungulates such as white-tailed deer and moose will “shield” their offspring by giving birth close to houses and villages, utilizing the local predators’ fear of humans to create a safe environment for their offspring to grow up.

Wildlife researcher Hugh Webster said that research about animals fearing humans shows that “human impacts on animal behavior are even more wide-reaching than we thought. Perhaps the key point is that we need to identify the most disturbance-sensitive species and engineer protections for them that allow freedom from this pervasive fear,” writes Phoebe Weston, a biodiversity writer for the Guardian.

In the animal kingdom, humans now occupy a unique role, surpassing all other predators in lethality and reshaping the natural order through unchecked consumption and industrial-scale exploitation. Our presence instills a pervasive fear across ecosystems, altering animal behavior and disrupting millennia-old predator-prey dynamics. Yet this super predator status comes with unprecedented responsibility. Unlike other apex predators, humans possess the awareness, technology, and moral capacity to recognize the consequences of our actions and to mitigate the harm we inflict. The question before us is whether we will continue to exploit the web of life for short-term gain or harness our intelligence and ingenuity to protect it—ensuring that future generations inherit a planet where humans are not feared as destroyers, but remembered as stewards of the living world.