Some Myths Regarding the Genesis of Enterprise

Not only were “modern” elements of enterprise present and even dominant already in Mesopotamia in the third millennium BC, but the institutional context was conducive to long-term growth.

Introduction

If a colloquium on early entrepreneurs had been convened in the early 20th century, most participants would have viewed traders as operating on their own, bartering at prices that settled at a market equilibrium established spontaneously in response to fluctuating supply and demand. According to the Austrian economist Carl Menger, money emerged as individuals and merchants involved in barter came to prefer silver and copper as convenient means of payment, stores of value, and standards by which to measure other prices. History does not support this individualistic scenario for how commercial practices developed in the spheres of trade, money and credit, interest and pricing. Rather than emerging spontaneously among individuals “trucking and bartering,” money, credit, pricing and investment for the purpose of creating profits, charging interest, creating a property market and even a proto-bond market (for temple prebends) first emerged in the temples and palaces of Sumer and Babylonia.

The First Mints Were Temples

From third-millennium Mesopotamia through classical antiquity the minting of precious metal of specified purity occurred was by temples, not private suppliers. The word money derives from Rome’s temple of Juno Moneta, where the city’s coinage was minted in early times. Monetized silver was part of the Near Eastern pricing system developed by the large institutions to establish stable ratios for their fiscal account-keeping and forward planning. Major price ratios (including the rate of interest) were administered in round numbers for ease of calculation (Renger 2000[1] and Creating Economic Order by Michael Hudson and Cornelia Wunsch 2004).

The Palace Forgave Excessive Debt

Instead of deterring enterprise, these administered prices provided a stable context for it to flourish. The palace estimated a normal return for the fields and other properties it leased out, and left managers to make a profit—or to suffer a loss when the weather was bad or other risks materialized. In such cases shortfalls became debts. However, when the losses became so great as to threaten this system, the palace let the agrarian arrears go, enabling entrepreneurial contractors with the palatial economy (including ale women) to start again with a clean slate (Renger 2002). The aim was to keep them in business, not to destroy them.

Flexible Pricing Beyond the Palace

Rather than a conflict existing between the large public institutions administering prices and mercantile enterprise, there was a symbiotic relationship. Mario Liverani[2] points out that administered pricing by the temples and palaces vis-à-vis tamkarum merchants engaged in foreign trade “was limited to the starting move and the closing move: trade agents got silver and/or processed materials (that is, mainly metals and textiles) from the central agency and had to bring back after six months or a year the equivalent in exotic products or raw materials. The economic balance between central agency and trade agents could not but be regulated by fixed exchange values. But the merchants’ activity once they left the palace was completely different: They could freely trade, playing on the different prices of the various items in various countries, even using their money in financial activities (such as loans) in the time span at their disposal, and making the maximum possible personal profit.”

Mesopotamian Institutions Boosted the Commercial Takeoff

A century ago it was assumed that the state’s economic role could only have taken the form of oppressive taxation and overregulation of markets, and hence would have thwarted commercial enterprise. That is how Michael Rostovtzeff[3] depicted the imperial Roman economy stifling the middle class. But A.H.M. Jones[4] pointed out that this was how antiquity ended, not how it began. Merchants and entrepreneurs first emerged in conjunction with the temples and palaces of Mesopotamia. Rather than being despotic and economically oppressive, Mesopotamian institutions and religious values sanctioned the commercial takeoff that ended up being thwarted in Greece and Rome. Archaeology has confirmed that “modern” elements of enterprise were present and even dominant already in Mesopotamia in the third millennium BC, and that the institutional context was conducive to long-term growth. Commerce expanded and fortunes were made as populations grew and the material conditions of life rose. But what has surprised many observers is how much more successful, fluid and also more stable economic organization was as we move back in time.

Ex Oriente Lux

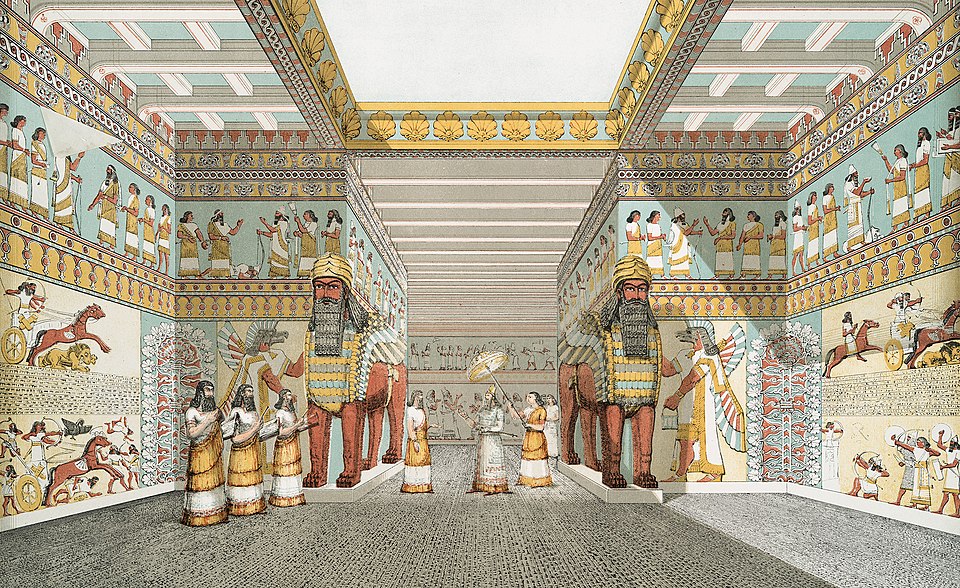

Growing awareness that the character of gain-seeking became economically predatory has prompted a more sociological view of exchange and property in Greece and Rome (e.g., the French structuralists, Leslie Kurke[5] and Sitta von Reden,[6] and also a more “economic” post-Polanyian view of earlier Mesopotamia and its Near Eastern neighbors. Morris and Manning[7] how the approach that long segregated Near Eastern from Mediterranean development has been replaced by a more integrated view (e.g., Braudel 1972[8] and Hudson 1992,[9] in tandem with a pan-regional approach to myth, religion[10] [11], and artworks.[12] The motto ex oriente lux now is seen to apply to commercial practices as well as to art, culture and religion.

Individualism Was a Symptom of Westward Decline

For a century, Near Eastern development was deemed to lie outside the Western continuum, which was defined as starting with classical Greece circa 750 BC. But the origins of commercial practices are now seen to date from Mesopotamia’s takeoff two thousand years before classical antiquity. However, what was indeed novel and “fresh” in the Mediterranean lands arose mainly from the fact that the Bronze Age world fell apart in the devastation that occurred circa 1200 BC. The commercial and debt practices that Syrian and Phoenician traders brought to the Aegean and southern Italy around the eighth century BC were adopted in smaller local contexts that lacked the public institutions found throughout the Near East. Trade and usury enriched chieftains much more than occurred in the Near East where temples or other public authority were set corporately apart to mediate the economic surplus, and especially to provide credit. Because the societies of classical antiquity emerged in this non-public and indeed oligarchic context, the idea of Western became synonymous with the private sector and individualism.

- ↑ A.C.V.M. Bongenaar, ed., “Das Palastgeschäft in der altbabylonischen Zeit”, Interdependency of Institutions and Private Entrepreneurs: Proceedings of the Second MOS Symposium (Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 1998), pp. 153–83. Michael Hudson and Marc Van De Mieroop, eds. “Royal Edicts of the Babylonian Period—Structural Background,” Debt and Economic Renewal in the Ancient Near East, (Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2002), pp. 139–62.

- ↑ J. G. Manning and Ian Morris, eds., “The Near East: The Bronze Age,” The Ancient Economy: Evidence and Models, (Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2005), pp. 47–57, 53-54.

- ↑ M. Rostovtzeff, The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1926).

- ↑ A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–610: A Social, Economic, and Administrative Survey, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964).

- ↑ Leslie Kurke, Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold: The Politics of Meaning in Archaic Greece. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999).

- ↑ Sitta Von Redden, Exchange in Ancient Greece, (London: Duckworth,1995).

- ↑ J. G. Manning and Ian Morris, eds., The Ancient Economy: Evidence and Models, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005).

- ↑ Fernand Braudel (author) Sian Reynolds (translator), The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, (New York: Harper & Row, 1972).

- ↑ Michael Hudson, “Did the Phoenicians Introduce the Idea of Interest to Greece and Italy—and If So, When?” in Greece between East and West 10th—8th Centuries BC, ed. Gunter Kopcke and I. Tokumaru, (Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern), pp. 128–143.

- ↑ Walter Burkert, Die orientalisierende Epoche in der griechischen Religion und Literatur. (Heidelberg, Germany: Winter, 1984).

- ↑ M.L. West, The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997).

- ↑ G. Kopcke and I. Tokumaru, ed. Greece between East and West: 10th-8th centuries BC, (Mainz: von Zabern, 1992), pp. xviii, 185, illus. DM98.