The Multi-Million-Year Path to Becoming Human—Are We Actually There Yet?

A conversation with the legendary evolutionary thinker and archaeologist, Eudald Carbonell.

Our chapter in the human evolutionary story is one of a globally connected population that has ballooned thanks to a suite of recent technologies. We frequently congratulate ourselves on these achievements, unique to the animal kingdom. But what if the celebrations are a little premature? Should we take into consideration that more phases of development will come in mind, behavior, and even appearance? Can we identify where we are in the process and what the pathways of change look like?

These are the kinds of questions that can keep professor Eudald Carbonell up at night. Carbonell is one of the most prominent archaeologists and thinkers on human evolution on the international stage today. He is best known as the co-director of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, Sierra de Atapuerca archaeological complex in Burgos, Spain, home to one of the longest records of human evolution known to science. A professor at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Carbonell also established the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution in Tarragona, Spain, where he continues to mentor students and researchers.

One of Carbonell’s great legacies is a conceptual framework for thinking about the human evolutionary process that he calls “hominization and humanization.”

In an important summary paper of his concept that we have translated with his approval, Carbonell explains hominization as:

“… a biological process in which a series of morphological and ethological changes in the primate order generate a structure with enormous evolutionary potential. This process involves, in addition to the genetic material that carries the information, the continuous change in ecological conditions to which these primates must adapt in order to survive. … In the long process toward humanization, humans have undergone a series of acquisitions—or improvements on previous acquisitions—that have made our current uniqueness possible.”

Carbonell wants us to understand that the hominization and humanization processes are two sides of the same coin. And that the humanization process has its own trajectory, which includes an active choice in our fate.

“Humanization must be seen as an evolutionary state of being that our species has not yet attained, but toward which we—as a species—can aspire: Humanization, as a systemic structural acquisition, represents a cosmic awakening, a singularity composed of multiform acquisitions that have allowed us, over time, to break with the inertia of the past and overcome natural selection to delve into what is currently unknown. It is essential to begin by understanding the initial concept, which provides us with the foundation of knowledge that makes the process of humanization possible and, therefore, places us right at the beginning of the entire human adventure.”

Initially, straitjacketed by biological limits, our ancestors eventually invented the technologies that would come to rewrite the rules. We are completely reliant on culture and symbolic communication for this stage of extraordinary economic development and population growth.

Carbonell’s thinking and published research have influenced scholars, including us, to consider whether the next phases of human development are only possible if we can take guidance from what this revolutionary deep-time archaeology is teaching us. We met with Carbonell to discuss these ideas and reflect on the wisdom he has attained over the decades.

Jan Ritch-Frel and Deborah Barsky: Your concept of hominization to humanization is a powerful framework for understanding human origins and our own framework. Can you briefly describe the meaning of this process?

Eudald Carbonell: This concept describes a hybridization process between biological and cultural traits. Hominization refers to all the biological developments characterizing the human evolutionary process. For example, when early hominins adopted an erect stature and fully bipedal locomotion, this was an important shift that liberated the hands from locomotory tasks and led to crucial modifications of the brain.

Humanization refers to all of the social and cultural developments that are associated with the different stages of human biological evolution. The concept of humanization is distinct from hominization, but their relationship should not be seen as one of coevolution but rather one of integral evolution. I don’t like the concept of coevolution. Instead, I propose the idea of evolutionary integration, wherein one incidence triggers another, engaging a process of reproduction through retro-alimentation. So, when I speak about hominization and humanization, I am referring to a process of hybridization of both biological and cultural traits.

Ritch-Frel and Barsky: New data emanating from archaeogenomics indicate a braided human evolution pathway: What do hominization and humanization tell us about the culmination of this process and our own experiences of being and becoming?

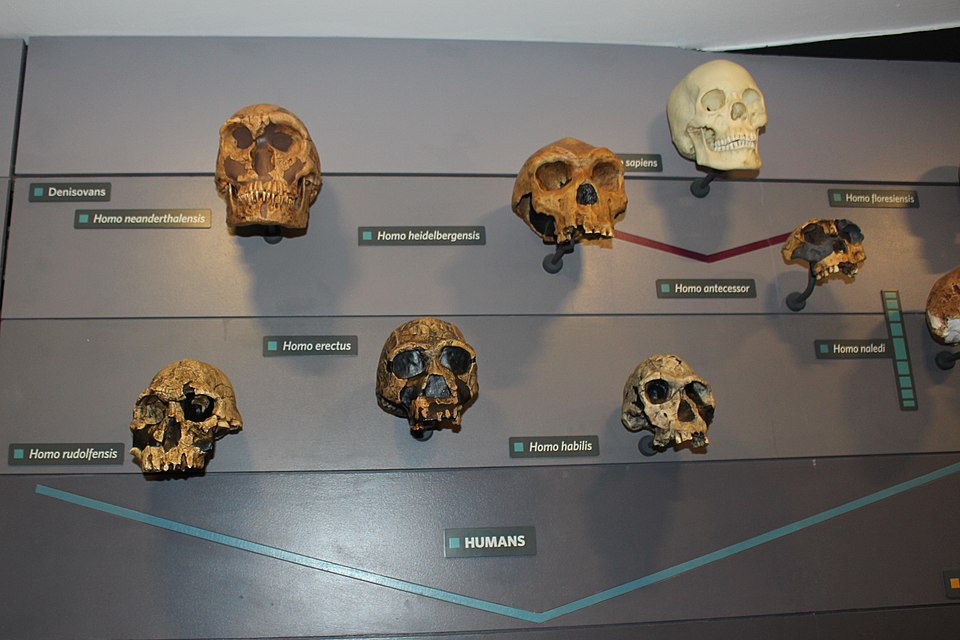

Carbonell: The evolutionary process of hominization and humanization is very complex. Previously, it was conceived of as a linear phenomenon—occurring sequentially—but it is not. In fact, it is plural and very multifaceted, like a bush with many branches. For example, advances in genetic studies (paleogenomics) now demonstrate that we are a hybrid of the many species with which we coexisted in Paleolithic Eurasia at different times, like the Neandertals and the Denisovans. We have also learned that anatomically modern humans emerged from yet another hybrid species much earlier than previously thought. In reality, the story of our genus Homo is very complex. I agree with my good friend, the famous paleoanthropologist Tim White, who said that Homo erectus and Homo sapiens are actually the same, in the sense that they represent a single evolutionary branch composed of a long succession of distinct individuals.

Modern humans are the result of multiple hybridization events. Only some 40,000 years ago—when the last known hybridization took place—the genomes recorded from some fossils of modern human individuals, who lived in Eurasia, have revealed relatively high percentages of Neandertal and Denisovan inputs. That means that H. sapiens emerged as a result of genetic drift; presently, our species has predominated as an outcome of this supersystem, but we are hybrids. We are not what we thought we were.

Ritch-Frel and Barsky: A lifetime like yours spent studying prehistory must allow you to develop original perspectives: Is the life of an archaeologist really the fantastic journey that most people think it is?

Carbonell: When you work, you always encounter deceptions. But the truth is, I have been obsessed with human evolution for many decades. Now that I am [72 years old], I feel I am ready to work on the future because I think that our species should know where it is headed. But my experience has also taught me that in order to think about where we are going, we need to investigate the past.

To me, the past and the future are the same and can be considered as having a linear quality, but only if we know the whole sequence. So, to speak with more authority about the future, we need to know the past. Without this knowledge, we cannot adequately develop our minds, our consciousness, our human intelligence.

In my opinion, we should define how we want to shape our future; what we want as a species. Do we want to be 4 billion people in the world? Do we want to be more cooperative? Do we want to be more united? Or do we want to disconnect? Once we know what we want to be, then we can look to the past to see what we need to do to get there. Do we want to be more eco-social? Do we want to show more respect to the natural and historic patterns we come from? Or do we want to break it all down—and even destroy ourselves? That is the first thing that we need to decide. If we don’t want to destroy ourselves, then we must find better ways to cooperate.

Ritch-Frel and Barsky: Archaeologists develop a special perspective because they spend more time than most people thinking about human evolution. Do you think this kind of training could be useful for other professions?

Carbonell: Yes, exactly. In fact, I have proposed to integrate a new class into the educational system, from as early as primary school and then also in secondary and university levels, which I have named: Human Social Autecology. Even if this class is taught for only one hour a week, from a young age, when one enters the educational system, let’s say from four or five years old, it could provide our youth with a new vision of the world. The class should be designed to provide a synthesis and should include a wide range of topics, like zoology, biology, sociology, and other subjects.

Acquiring and truly integrating such a wide body of knowledge would be beneficial to humanity on the whole because it would help individuals to learn to think critically and more fittingly assume a more acceptable basic behavioral code based on Human Social Autecology.

Ritch-Frel and Barsky: Do you think the new waves of information coming out of human origins research can address questions that challenge modern humanity?

Carbonell: I think we are an imbecile species. And for that reason, we sometimes believe and act on imbecile ideas that have no scientific proof. Learning about human evolution serves to understand ourselves. Human beings are profoundly evolutionary and evolved.

I sincerely believe that all of these notions, like creationism, in its various forms, or fake news—all of these nonsensical ideas are linked to our failure as a species. They teach us nothing and cannot be demonstrated. For example, the idea that the world is flat; everyone knows that it is round because it has been demonstrated scientifically. Everybody also knows that we originated from primates, that we are primates. Although with a significant difference, we are cultural primates. We are intelligent thinking beings.