We forget most of our dreams. So why do we have them?

This article was produced by

Earth • Food • Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Guides

Articles with Similar Tags

Authors in Science

Introduction

No one knows why we dream. It stands to reason that dreams have some purpose because nearly everyone dreams, and we dream 3 to 6 times every night. People typically have several dreams each night that grow longer as sleep draws to a close. Over a lifetime, a person may dream for five or six full years. The types of dreams you have change depending on your age and life circumstances.

Psychology Today offers a simple definition: “Dreams are the stories the brain tells during the REM (rapid eye movement) stage of sleep.” But why does the brain tell these stories to itself?

Dreams can be a portal into your mental state, says Dr. Rahul Jandial, neurosurgeon, neuroscientist, and author of This is Why You Dream: What Your Sleeping Brain Reveals About Your Waking Life. Some dreams, he believes, are worth paying attention to; others not so much. It’s worth considering the possible causes of an intense dream. “Dreams with a strong emotion and a powerful central image, those are ones not to ignore,” he says. Strong, negative emotional states like anxiety and stress are known to trigger bad dreams. This may be why up to 80 percent of those with PTSD experience frequent nightmares.

If they recur, anxiety dreams are among those we need to heed. When you’re experiencing more stress or anxiety, you tend to dream more, too. Nightmares or stressful dreams—for example, about being chased or being in a frightening situation—are also common when you’re anxious, says behavioral sleep medicine expert Michelle Drerup at the Cleveland Clinic. “That’s one of the theories of why we dream. Our dreams might help us process and manage our emotions.” Culture or societal norms may also be a factor, she notes. “There seems to be some cultural influence on dreams. For example, the same type of dream might be more common in Germany.”

“The dreaming brain is serving a function, and if it gives you a nugget of an emotional and visual dream, reflect on that,” Jandial notes. “That’s a portal to yourself that no therapist can even get to.”

Paying attention to powerful dreams is easier said than done since we forget, on average, 95 percent of our dreams when we wake up.

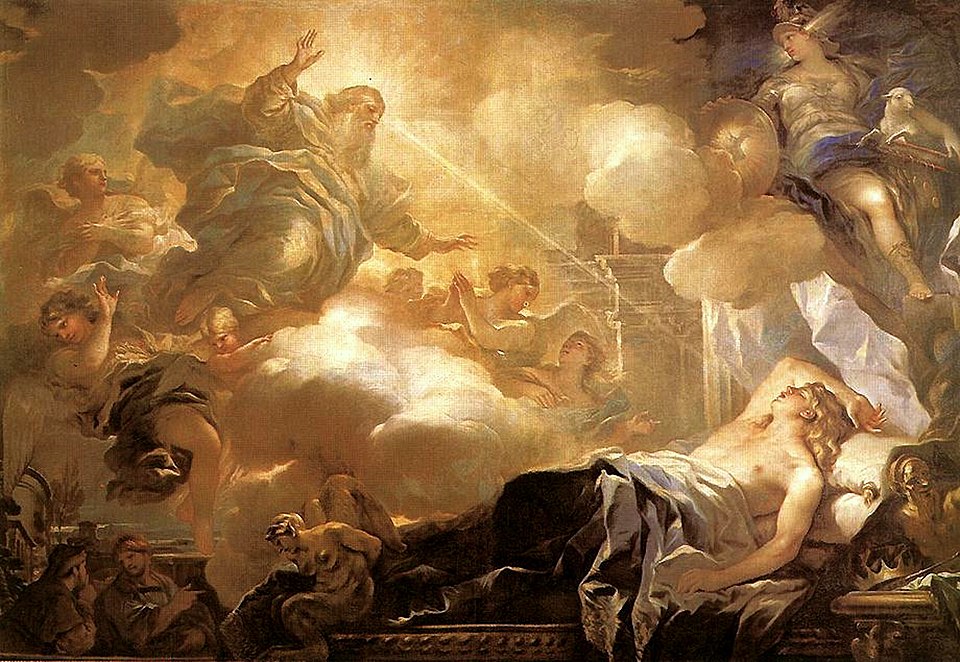

So, if we forget most of our dreams, why do we have them? Theories abound. Freud believed dreams express repressed content, ideas, or themes. Carl Jung, who famously broke with Freud over the role of the unconscious, maintained that “… the dream is a spontaneous self-portrayal, in symbolic form, of the actual situation in the unconscious.”

According to a more recent theory, dreaming can help you learn and develop long-term memories. In other words, dreams consolidate memory tasks and learning that have occurred during the day. In that respect, they perform a clerical function. Other theories see dreams as a unique state of consciousness that incorporates the present experience, processing of the past, and preparation for the future.

More pertinently, dreams may prepare us for possible future threats, which is related to the theory of dreams as a cognitive simulation of real-life experiences, a subsystem of a waking default network (involved in daydreaming). In other words, we can rehearse our feelings in our dreams. “… [D]reaming may represent important cognitive functioning,” says Drerup, “Brain activity that occurs when we’re dreaming is similar to the memory processing brain activity we experience when we’re awake.” Dreams may also provide a “safe space” where problems that are too overwhelming, contradictory, or disturbing to deal with by the conscious mind adequately can be integrated and resolved.

Dreams could also be an instant replay of the day’s events, charged with emotions and involving many jump cuts and strange juxtapositions. This is called the continuity hypothesis, which states that most dreams reflect the same concepts and concerns as our waking thoughts.

Dreams may spur creativity. In this theory, dreaming aids in problem-solving, coming up with solutions that may have eluded the dreamer’s waking life. In one famous instance, August Kekulé, a 19th-century German chemist, had a dream that featured the ouroboros (the mythical snake eating its tail), which inspired him to derive the ringlike composition of carbon atoms that make up the benzene molecule, a problem that he’d failed to solve in waking life. Dmitri Mendeleev arrived at his periodic table in a dream. “All the elements fell into place as required,” he recounted in his diary. “Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper.” Cosmologist Stephon Alexander dreamed about the role of symmetry in cosmic inflation. In contrast, Einstein’s dream, in which he saw cows jumping up and moving in a wavelike motion, led to one of the central tenets of his theory of relativity.

Dreams may have a culling function. It’s the brain’s way of “straightening up,” removing information that is not useful or incorrect. There is also a theory that dreams have no purpose whatsoever. Dreams could be incidental to sleep, a gratuitous process that contains the waste products of the day to which we may be tempted to impute importance that they don’t deserve.

With so much unknown about dreams and so many competing theories, dream experts in neuroscience and psychology continue their research with the possibility that they will never conclude why we dream.

Nonhuman Animal Sleep

All animals sleep. But do they dream? There is some evidence that they do, although obviously, they can’t tell us. If there are exceptions, they include dolphins and whales because underwater, only half of their brains are asleep at any given time. The behavior of animals while asleep—rapid eye movement, muscle twitching, and involuntary vocalizations—is similar to what humans observe while dreaming. A young elephant named Ndume, captured in Kenya after poachers killed his family, would wake up crying in the middle of the night, a response that Ndume’s handlers believed was equivalent to night terrors that traumatized humans would experience.

In the 2024 book When Animals Dream, the author David Peña-Guzmán, a professor of humanities and liberal studies, examines the evidence that strongly indicates that animals of all kinds dream and, further, that, like humans, they go through distinct sleep phases. (Bees have three; octopuses, two.) Research in the 1960s by the French neuroscientist Michel Jouvet on cats showed that their brain activity while asleep was no different from what would happen in the brains of cats in waking life when their prey was within striking distance. An octopus undergoes a series of color changes while asleep, leading some researchers to believe that these changes in their skin pigmentation may suggest that octopuses are dreaming.

Rats are known to “replay” movements in their sleep that they make while awake. Researchers reached this conclusion based on rats compelled to navigate mazes. While the rats were asleep, researchers observed that specific brain structures—maplike arrays of neurons—were activated, suggesting that the rats were dreaming about how they made their way through a maze while conscious. This behavior is hardly unique to rats. Neurological and electrophysiological measurements of the brains of various species have shown that they see, hear, and feel specific, identifiable scenarios in their sleep that appear to be direct replays of experiences they’ve had in waking life. Biologists studying zebra finches, an Australian species of bird that learns unique songs passed down from its family, found that in juveniles, the neurological patterns matched precisely, note for note, what they sang during the day. In other words, the birds were practicing in their dreams.

To dream experts, the existence of dreamlike states in animals raises the issue of what evolutionary purpose dreams might serve. Did dreaming arise among many species independently in the hundreds of millions of years that life has existed, or did it evolve once in some probably extinct creature and then persist as organisms branched out to follow their evolutionary trees? Some experts contend that the first creature to dream was a small, wormlike, sea-dwelling creature with no eyes and limited motion. We can’t imagine what use dreams might be for such a creature. Peña-Guzmán doesn’t take a position on whether such a creature was responsible for the first dreams or whether vertebrates (including us) and cephalopods like octopuses and cuttlefish can trace their capacity to dream back to a common ancestor.

Phases of Sleep

There are five phases of sleep in a sleep cycle. The first phase is characterized by light sleep, slow eye movement, and reduced activity. In the second phase, eye movement ceases and brain waves are slower, marked by occasional bursts of rapid waves called sleep spindles. In the third phase, delta waves appear—extremely slow waves interspersed with smaller, faster waves. In the fourth phase, delta waves predominate almost exclusively. This is called deep sleep because it is difficult to wake the sleeper up.

However, the fifth phase—rapid eye movement (REM) sleep—interests us because almost all dreaming occurs during the REM phase. REM sleep is characterized by rapid, irregular, and shallow breathing, eye jerking in all directions (that’s the rapid eye movement), and the temporary paralysis of the muscles. At the same time, the heart rate increases, blood pressure rises, and men can experience erections. Brain activity also increases during REM sleep, similar to wakefulness. Because brain activity intensifies compared to the non-REM phases, it may help explain the distinct types of dreams that are more vivid and fantastical. Dreams in other phases, by contrast, are typically more coherent and based on thoughts and memories that refer to a specific time and place. Most REM sleep, which cumulatively accounts for about two hours every night, takes place later in the sleep cycle, intensifying the closer we are to waking. Each dream lasts between 5 and 20 minutes.

“Dreams are mental imagery or activity that occur when you sleep,” explains Drerup, the sleep medicine expert at the Cleveland Clinic. “In REM sleep, we have less autonomic stability. Our heart rate increases. We don’t have the kind of steady, calm respiration that we do during other stages of non-REM sleep.” In all cases, researchers have to depend on first-person accounts of individuals who recall enough of their dreams to recount them. Babies and other mammals have to go by inference since they can’t yet see inside the brain to observe the actual process of dreaming. “That’s part of the reason why [dreams are] still kind of mysterious—they’re difficult to study,” Drerup says.

What Are Dreams?

Dreams appear to be a universal phenomenon, but what do they mean? Dream interpretation has a long history. It was practiced by the Sumerians, whose civilization flourished between 4100 and 1750 BCE, and Babylonians in the third millennium BCE. For these ancient civilizations, dreams held a religious significance. Dreams also enjoyed a prominent spiritual role in Ancient Egypt, where scribes would document them as long as the dreamer was important enough. (In the Old Testament, Joseph, who is sold into slavery by his brothers, subsequently wins the trust of the pharaoh because he proves able to interpret the ruler’s dreams.) For the Egyptians, dreams could have the force of commands or predictive power.

In the latter years of the 19th century, religion yielded to psychotherapy when it came to dream interpretation, most famously by Sigmund Freud, who perceived in dreams the expression of unconscious urges and wishes (especially regarding sex) that his patients wouldn’t dare consider, let alone act upon, in their waking life. Freud published his theories in his 1899 classic The Interpretation of Dreams. While Freud’s work has since come under fire and his interpretations debunked, his theories have been so well incorporated into our culture that they continue to influence how we interpret dreams.

Oneirology, the study of dreams, is no longer the realm of psychotherapists and has now been largely taken over by neuroscientists. Scientists, though, are still flummoxed by dreams. What is their function? Is there a discrete part of the brain responsible for generating dreams, or do the actions of several parts produce them? That they haven’t yet come up with a widely accepted hypothesis to explain the origin or purpose of dreams hasn’t discouraged them.

No cognitive state has been studied as extensively as dreaming. The dilemma scientists confront is the same as the Sumerians and Egyptians grappled with: how do dreams produce an experience that is often so vivid and emotionally charged that they may seem to hold significance that experiences in waking life usually do not? Subjective reports of dreams—which is all that scientists like psychotherapists have to go on—tend to be related to waking life, however bizarre and discursive, reflecting preoccupations, vexations, fantasies, memories, and fears that dominate the conscious mind, featuring appearances by individuals who are well-known to the dreamer but also those whom the dreamer may never have met.

Certain elements are characteristic of most dreams. They are usually perceived from a first-person view. In other words, the action is seen by or involves the dreamer. With few exceptions (like lucid dreaming), dreams are involuntary. They are also surrealistic in that they don’t seem to be governed by the laws of logic or make any narrative sense. Many dreams evoke powerful emotions regardless of their apparent incoherence. Affection and joy are commonly associated with known figures and are used to identify them even when in the waking state; the same people didn’t evoke either emotional state.

Dreams typically feature individuals who are known to the dreamer. In a study of 320 adult dream reports, 48 percent of the figures who appeared in a dream were known by name to the dreamer; 35 percent involved people whose role, if not necessarily their name, were identifiable—a police officer, a teacher, a waiter—but they were distinguished by the fact that they had some role in waking life that the dreamer had experienced. In last place, 16 percent reported appearances by people they didn’t recognize. Facial recognition (45 percent) was the tipoff for most dreamers, followed closely by an intuitive sense (44 percent) or “just knowing.”

Dreams usually connect the dream state and waking life, however tenuously; this is known as the “continuity hypothesis.” (There is also a “discontinuity hypothesis,” which holds that the dream and waking states are fundamentally distinct and unrelated.) Nonetheless, evidence suggests a connection, possibly a strong one. Studies of the dreams of psychiatric patients and patients with sleep disorders, for example, have found that their daytime symptoms and problems are reflected in their dreams.

On the other hand, habits, interests, or preoccupations that dominate a person’s waking life can also play an essential part in their dream life. In a study of 35 professional and 30 non-musicians, the musicians experienced twice as many dreams featuring music as non-musicians. The frequency of music-associated dreams corresponded to when the musicians began formal instruction, not the degree to which they played or listened to music in daily life. The music that they reported hearing, though, was not necessarily music they were familiar with in their waking life, suggesting that original music can be created in dreams.

Whatever else dreams mean (or don’t), their interpretation is big business. A category known as dream books is intended for readers who want to determine the meaning of their dreams. In the Apple app store, users can download an app and “step into a realm of self-exploration and personal growth with DreamsBook, your comprehensive guide to dream interpretation and analysis.” The app purports to offer “a deeper understanding of your psyche, assist you in identifying your life patterns, aid in self-discovery, and even help improve your sleep quality.”

Or you can walk into a bookstore and pick up a copy of Dream Moods: A to Z Dream Dictionary or The Complete Dream Book: Discover What Your Dreams Reveal About You and Your Life and find out how to apply the insights from dreams to waking life. There is no evidence, though, that any dream book or app can guide the meaning of people’s dreams, much less any clarification that the lessons they teach can have practical use. The lack of scientific validity, however, hasn’t stopped writers from continuing to churn out books designed for the insatiably curious who remain convinced that their dreams can be puzzled out and provide them with valuable insights.

Do We Dream in Color?

Whether we dream in color often depends on when we were born. Researchers discovered in a 2011 study that about 80 percent of participants younger than 30 dreamed in color, but only 20 percent at 60 or older did so. The same study found that the number of people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s dreaming in color increased from 1993 to 2009, suggesting that color television might have been a factor that may explain why another study of dream reports (using questionnaires and dream diaries) found older adults had more black and white dreams than the younger participants.

Older people, however, reported that their dreams, whether in black and white or in color, were equally vivid, whereas those who were younger said that their black and white dreams were of poorer quality.

Gender Differences

A study of dreams experienced by 108 males and 110 females found that the participants’ dream content did not differ regarding aggression, friendliness, or sexuality. However, women’s dreams featured more children, families, and indoor environments than men’s.

Dreams in Pregnancy

Studies comparing the dreams of pregnant and nonpregnant women showed that women who were not pregnant had fewer dreams about infants and children. Perhaps more surprisingly, until the late third trimester, most pregnant women didn’t have many dreams about infants and children, either. In the third trimester, though, the pregnant woman was more likely to dream about pregnancy, fetuses, and childbirth. They also reported having more morbid content in their dreams than women who were not pregnant.

Nightmares

Nightmares are disturbing dreams that appear to be symptomatic of anxiety and stress. Dreams of being chased, falling off a cliff, or showing up in public naked, all of which are common, may be due to stress. Fear, emotional problems, and illness may also factor into the occurrence of nightmares. Trauma, as well, may play an essential part in triggering nightmares. One manifestation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is called “re-experiencing” or, more simply, “flashbacks.” These involuntary recollections often manifest in the form of nightmares that can cause significant emotional distress. Even when the nightmares may not involve flashbacks, they may have a strong symbolic or indirect connection to the traumatic event.

For most people, nightmares are infrequent, but some suffer from a form of sleep disorder called nightmare disorder. “With nightmare disorder, you have these distressing nightmares that are repetitive,” says Drerup of the Cleveland Clinic. “They occur frequently. They wake you from sleep. You can’t get back to sleep [afterward]. You have a panicked feeling upon awakening and take a while to reorient.” Jandial, the neurosurgeon and author, adds: “Reports of nightmares and erotic dreams are nearly universal.”

All the same, nightmares are not very common. Half of adults report experiencing nightmares from time to time, but 10 percent have recurring episodes. Children more than adults have nightmares, although some child psychiatrists believe that’s because they have a difficult time distinguishing between reality and fantasy.

Nightmares are not only frightening to experience, but they leave people feeling debilitated and tired the next day. As a treatment, Drerup recommends imagery rehearsal therapy. “This treatment has some really significant research backing behind it,” she says. “You work with your therapist to rewrite the nightmare to contain less disturbing content and then practice the new dream imagery during the daytime.” She describes it as guided imagery, which exposes the patient to new content to lessen the disturbing impact of the nightmare. “The image you’re practicing can replace or decrease the frequency of that disruptive nightmare or completely eliminate it altogether.”

Another treatment recommended for people who report frequent nightmares is to try to focus on positive elements of their day immediately before bed or to avoid rumination and dwelling on disasters. For nightmares originating with PTSD, visualization treatments in which patients replay traumatic memories in “safe” ways have shown potential to bring relief.

People who have sleep disorders, including those with insomnia and narcolepsy, may recall their dreams better than those who do not. The negative nature of the dreams and underlying stress may explain their improved recall.

Lucid Dreams

Lucid dreaming refers to dreams in which the dreamer controls the dream’s content. It also occurs when the dreamers suddenly realize they are dreaming and gain control over the dream. If it does take place, lucid dreaming usually occurs in late-stage REM sleep. Most people, though, do not report having lucid dreams. In fMRI studies, lucid dreaming involves the activation of the prefrontal cortex and a cortical network that includes the frontal, parietal, and temporal zones. Its popularity is due to the belief that lucid dreaming can boost creativity and confidence and reduce stress.

Numerous groups and communities prioritize lucid dreaming, although evidence to support individual initiative in lucid dreaming is scant. The capacity for lucid dreaming differs from one individual to another. Lucid dreamers report willing themselves to fly, fight, or act out sexual fantasies. Advocates of the practice hold that you can train yourself to have lucid dreams by starting with regular recordings of dream experiences to gain a greater awareness of the conscious roles the dreams may already play in common scenarios, a kind of homework for taking control over dreams. Another strategy involves waking up two hours earlier than usual, staying awake briefly, and returning to sleep. The idea is to increase awareness of what occurs in late-stage REM sleep, aiming to direct the dreams in this stage.

Dreams and Memories

We don’t go to sleep to forget. On the contrary, one study showed that sleep does not help people forget memories they’d prefer to bury. Instead, it seems that sleep might dredge up memories that we’ve tried to suppress, an idea that inspired Freud’s concept of “repression.” Freud described a category of dreams known as “biographical dreams,” which he theorized were based on the troubling historical experiences of an infant who, unlike an adult, couldn't repress them. Even today, researchers hypothesize that these traumatic memories can reemerge in dreams and that they can help an individual reconstruct and come to terms with past trauma.

The connection between memories and dreams can be classified as either dreams in which memories of the last day are incorporated (the day-residue effect, as it’s known) or dreams that incorporate memories from several days before (the dream-lag effect). According to a study conducted by Canadian researchers in 2004, memories generally take a week to resurface in dreams.

They concluded that the dream-lag effect was more typical than the day-residue effect. The dream-lag effect has been reported in dreams that occur at the REM stage but not in other stages of sleep. Overall, though, only 1 to 2 percent of people report either effect in their dreams, compared to the 65 percent of people who report that their dreams reflect some aspect of their waking experiences.

Two types of memory typically occur in dreams. The first are autobiographical memories—short-term or those that go back many years. In autobiographical dreams, the recreated memories are usually fragmented and selective. The dreams may be part of a consolidation process, transforming them into long-term memories.

The second type consists of episodic memories, in which dreams are inspired or triggered by specific events like the 9/11 attacks or the assassination of JFK. A small study (with 32 participants) found that 80 percent of reports contained a low to moderate level of autobiographical memory incorporation. In contrast, only one person reported a dream that could be considered episodic (0.5 percent).

Forgetting and Remembering Dreams

Even though most people over 10 dream between 4 and 6 times each night, they rarely remember their dreams. Within five minutes after a dream, most people have forgotten 50 percent of their dreams. In another five minutes, they’ve forgotten all of them. We know how easy it is to forget our dreams, but why is it so hard to keep hold of them, and is there anything we can do to remember them?

The answer to the first question is unknown, but researchers have identified certain factors that may help people recall their dreams, both how much of the dream they remember and how vivid it is. Evidence suggests that recalling dreams becomes more difficult starting in early adulthood but not in older age. Dreaming also becomes less intense as the person ages. Men’s dreams change faster than those of women.

There are tricks to recalling dreams. For instance, the Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí would fall asleep in a chair holding a large key above a plate on the floor. When he nodded off, the key would fall from his hand, hit the plate, and make enough noise to rouse him. At that point, he would sketch what he’d remembered of the dream he’d just had. It is no coincidence that so many of his paintings were inspired by dreams. Jandial, while not relying on the drop of a key, says that most of his ideas come when he wakes slowly and then writes down what he remembers of his dreams. Most of the time, he admits that what he documents is not very promising. “But when there are good ideas, it’s from that time. It’s not from two o’clock with my espresso.”

It also seems that bad dreams, which may be related to emotional problems in waking life, are recalled more frequently and accurately than those relatively free from anxiety and worry. One study of college students examined whether dream recall and dream content would reflect the social relationships of the person dreaming. The student volunteers were assessed on multiple psychological factors, such as attachment, recall, and dream content.

Those who rated high on “insecure attachment” were more likely to report intense images in their dreams and that they were more emotionally charged. Participants rated as “preoccupied” were also more likely to remember their dreams than those assessed as “avoidant,” who ranked lowest in dream recall. That suggests that those participants who were coping with more emotional problems in their waking life were also more likely to remember their dreams, which, in the cases of the insecurely attached and preoccupied, were likely to be more intense.

No Dreams at All?

A minority of people don’t have any dreams (unlike those who never recall them). These people have a rare condition called Charcot-Wilbrand syndrome, which occurs as a result of focal brain damage (typically a stroke) that impairs the brain’s capacity to process visual information or “revisualize” images. According to neurologist Macdonald Critchley, in Charcot-Willard, “a patient loses the power to conjure up visual images or memories and ceases to dream during his sleeping hours.” In 2004, a 74-year-old woman with a blockage of her occipital artery, which is involved in transmitting visual imagery to the occipital lobe of the brain, ceased to have any dreams over three months.

Neuroscience of Dreams

Neuroimaging studies of brain activity during REM sleep have led scientists to believe that brain activity might be linked to specific dream features. They have focused on the paleocortical and subcortical limbic areas, which are active in the dream state. One 2014 study has linked frontotemporal gamma EEG activity to conscious awareness in dreams. The study found that electrical stimulation in the lower gamma band during REM sleep influences brain activity and may even induce self-reflective awareness in dreams.

Several bizarre features of dreams, such as delusional misidentifications of faces and places, have similarities with well-known neuropsychological syndromes that occur after brain damage.

The right and left hemispheres of the brain contribute in different ways to dream formation. One study concluded that dreams seem to originate in the left hemisphere, while the right contributes to the dream’s vividness, figurativeness, and affective activation. It’s as if one control mechanism tunes in the station while the other brings the broadcast into focus and adds color.

Dream recollection and intensity change over time. Dreams are affected by how a person experiences changes in sleep timing, structure, and electroencephalographic (EEG) activity.

Pain and Dreams

Pain is a complex phenomenon. Whether it exists independently or is a result of perception (such as what occurs with pain from phantom limbs), the pain is real for the person who experiences it. Self-reporting may be the only way that pain can be determined. There has yet to be any quantifiable way to assess the degree of pain. Studies have shown that realistic, localized painful sensations can be experienced in dreams, either through direct incorporation (the pain is felt because it originates from or occurs during the dream) or indirect incorporation in that it comes from memories of pain. Researchers have yet to establish a mechanism to explain the relationship between pain and bad dreams. Still, bad dreams generally occur during REM sleep, suggesting that pain experiences alter the dream content or that the amount of REM sleep is altered by the physiological effects of pain on the brain.

However, the frequency of pain dreams, even in subjects who have pain, isn’t as great as you might think. A study of 28 unventilated burn victims within days of their admission for their injuries showed that 39 percent reported dreams that involved pain and that 30 percent of their total dreams were pain-related. This group experienced reduced sleep, had more nightmares, and required a greater dosage of anti-anxiety drugs. They also tended to report more intense pain during therapeutic procedures. However, more than half of the burn victims in this study did not report pain dreams more than regular volunteers who were part of the control group.

Although researchers haven’t established a strong independent correlation between pain and pain in bad dreams, they believe a connection exists. Migraines, for example, may be associated with bad dreams. The reverse may also be true; bad dreams may occur during an ongoing migraine episode, or they may precede the onset of the most painful part of a migraine.

Studies on people with migraines also found that they reported dreams involving taste and smell more than people who didn’t suffer from migraines. This finding may suggest that specific cerebral structures, such as the amygdala and hypothalamus, may play a more significant role in producing migraines than neuroscientists have previously suspected.

Death in dreams

To study dreams about death, researchers chose a group that was preoccupied with death: those who had been admitted into a psychiatric facility after attempting to take their own lives. Those who had considered or attempted suicide or carried out violence were more likely to have dreams with content relating to death and destructive violence. Depressives had more dreams about death.

But for those who were in a hospital because they were very ill and fighting cancer, the results of dream studies were different. Neuroscientist Jandial, treating patients at City of Hope Cancer Center in Los Angeles, observed a phenomenon he terms “dreams to the rescue.” For some patients near the end of their lives, “even though the day is filled with struggle, the dreams are of reconciliation, of hope, of positive emotions. I was surprised to find that end-of-life dreams are a common thing, and they lean positive.”

Jandial found evidence that death may come with one final dream. “Once the heart stops, with the last gush of blood up the carotid [artery] to the brain, the brain’s electricity explodes in the minute or two after cardiac death… Those patterns look like expansive electrical brainwave patterns of dreaming and memory recall.”

Romantic Relationships and Dreams

Researchers have revealed a link between romantic attachment and the content of people’s dreams. One of these studies, conducted on 61 students who were in committed relationships for six months or longer, revealed a significant association. Asking participants to think about certain people before sleep increased the likelihood of the participant reporting dreaming about that person. If researchers asked the participant not to think about a particular person, it only increased dreams about them. The results were stronger when participants were asked to focus on a person they found romantically attractive (versus a person they were not attracted to).

The researchers relied on what is known as a secure base script. Attachment begins in childhood when parents are often the central attachment figures. Securely attached people rely on the secure base script, which includes three components: recognizing and displaying distress, seeking proximity to attachment figures, and problem-solving. Those with secure attachments have learned to expect support from others during distress and understand that their actions can reduce distress. In contrast, insecurely attached individuals often show avoidance as a defensive strategy in that it protects them from physical harm—should they display anger toward the attachment figure—and emotional harm—should their bids for attention be ignored yet again. Avoidant people may attempt to reject any information that could cause anxiety and activate the attachment system. These attachment behaviors are often unconscious, but they emerge in dreams. Those with an insecure attachment are more likely to have dreams of greater emotional intensity and “morbid” emotional content, as well as sleep problems such as nightmares, sleepwalking, and teeth grinding than secure individuals.

In surveys of dream content, a majority of people report erotic dreams. And for people in relationships, these dreams contain “high rates of infidelity, whether people report being in healthy relationships or unhealthy relationships,” says Jandial, neuroscientist and author. But erotic dreams have rules, too, he notes. “When you look at the pattern of erotic dreams, the acts seem to be wild, but the characters are surprisingly narrow. Celebrities, even family members, repellent bosses; it’s a small collection of people as a pattern.” Jandial and other researchers theorize that having sexual dreams about people familiar to us may be a feature our brains evolved to keep us open to procreation and increase the likelihood of the species’s survival.

Can Dreams Predict the Future?

Some researchers claim to have evidence that dreams offer a glimpse of the future, but there is not enough evidence to prove it. The phenomenon of precognitive dreams is connected to the experience known as déjà rêvé—the feeling of dreaming something before it happened. Déjà rêvé (which translates as “already dreamed”) is relatively common, especially among the young. As therapist and dream expert Leslie Ellis, PhD, says: “Dreaming is a phenomenon where time does not follow the strict linear rules of the day world. In dreams, we often have a mix of past, present, and possible future. Dreams that predict the future are called precognitive dreams, a close cousin of the déjà rêvé phenomenon.”

History records several instances in which dreams seem to foretell calamitous future events. Abraham Lincoln is said to have dreamed of his death. Ten days before his assassination, he had a dream in which he saw mourners gathered in the East Room of the White House, and one of them said that they were grieving a president who’d just been assassinated. Although Lincoln appeared “disturbed and frightened” when he recounted this dream, there are also stories that he believed that another president had been killed, not him. In 1966, a 10-year-old girl named Eryl Mai in South Wales woke to tell her mother that she’d dreamed that her school was no longer there and was covered by “something black.” A landslide, subsequently caused by waste from a coal mine in the village of Aberfan, obliterated the child’s school, killing 144 students (including Mai) and teachers. This disaster was evidently forecast in dreams by 76 different people. This led British psychiatrist John Barker to form the Premonition Bureau, which collected other reports of dreams that might be precognitive. (This not terribly successful effort is documented by Sam Knight in his 2022 book The Premonition Bureau: A True Story of Death Foretold). Barker’s was hardly the only attempt to document dreams that might forecast the future.

There may be perfectly logical explanations for such dreams that have nothing to do with psychic phenomena or ESP. Selective recall is one. A person may recall a dream that is more predictive of a future event than other dreams that do not. People with “tolerance for ambiguity” are likelier to experience premonitory dreams. That is, they are more prone to interpret an ambiguous dream as predictive of a future event. Those who believe in precognitive and paranormal dreams are likelier to have such dreams. And then there are individuals who, once they experience an event, may recall a dream that seemed to predict it.

Finally, some subconscious wishes may express themselves in a dream, even though the person is already consciously prepared to act on that wish. In this sense, the dream is considered precognitive when the dreamer’s mind is primed. For instance, you might dream of purchasing a new bed and then see an ad for a new one shortly after you wake up. But you might have been thinking about redecorating your house, so the dream only reflected that intention, even if it wasn’t uppermost in your consciousness.

This isn’t to say that there might not be some science behind the experience of precognitive dreams. In his book, The Oracle of the Night: The History and Science of Dreams, the neuroscientist Sidarta Ribeiro allows for the possibility that dreams could have a “predictive” function. “[Your dream is] not a deterministic oracle that can predict what’s going to happen, but rather a very sophisticated, probabilistic, neurobiological machine” that simulates possible futures based on what happened in the past. “On top of the neurological processes at play, you have the dream level that's symbolic and related to your life in a predictive manner,” meaning that some of the dreams may eventually prove true to your experience. Our dreams present us with various scenarios that show us what the future could look like based on what we know of the past. One of those scenarios may be close to what occurs. Whether that means the dream is precognitive or more like a game of roulette where you make the right bet sooner or later is an unanswerable question.