Climate Change Is Worsening Seasonal Allergies by Boosting Plant Pollen Production

Higher carbon dioxide levels and warmer temperatures are causing plants to increase their pollen production.

Introduction

As the seasons shift into spring and summer, flowers bloom, trees turn green, and the days grow longer and sunnier. However, for many, this time also marks the start of allergy season in the United States, which can begin as early as February in warmer regions and persist through early summer. Tree pollen usually kicks things off in early spring, followed by grass pollen in late spring and summer. Later in the year, fall allergies—primarily triggered by weed pollen, such as ragweed—begin in late summer and continue into autumn.

In 2023, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 25.7 percent of U.S. adults were diagnosed with seasonal allergies. That means about a quarter of Americans suffer from watery eyes, a tickly throat, and a runny nose. Pollen can make breathing outdoor air difficult. However, it’s getting worse: With climate change altering weather patterns and triggering an earlier and more prolonged high pollen count, we may all be experiencing more sneezing and breathing-related health issues than usual.

“If you live with seasonal allergies and feel like the pollen seasons feel longer and longer every year, you may be right,” writes Paul Gabrielsen, of the University of Utah. “[P]ollen seasons start 20 days earlier, are 10 days longer, and feature 21 percent more pollen than in 1990—meaning more days of itchy, sneezy, drippy misery.”

But it’s not just happening in the U.S., and the impacts can be fatal. In November 2016, a rare and deadly event known as “thunderstorm asthma” struck Melbourne, Australia, overwhelming emergency services as thousands experienced sudden, severe breathing problems. Hospitals saw a massive surge in asthma-related cases, with 10 deaths and many more struggling to breathe within minutes of the storm. Scientists later explained that storm activity had broken up pollen particles, releasing allergenic proteins into the air that triggered asthma attacks, even in people with no prior history of the condition.

Allergy specialist Dr. Kari Nadeau, chair of the Department of Environmental Health at the Harvard School of Public Health, blames global warming. “There are these extreme, chaotic conditions that climate change is associated with,” Nadeau told Boston 25 News in March 2023. “And that warming is adversely affecting our pollen seasons.

“Trees are getting the wrong message, and they’re releasing pollen earlier in the season,” said Nadeau. “So my patients, for example, otherwise would have started allergy season in March, now they’re having allergy season start in January–February.”

Pollen: A Pervasive Problem

Hay fever isn’t new. It was first described in 1819 when physician John Bostock presented a novel case to the Medical and Chirurgical Society, calling it a “case of a periodical affection of the eyes and chest.” It was the first recorded description of what he later called “catarrhus aestivus,” or summer catarrh, which would become what we know today as hay fever.

Since the first reported case in 1819, however, hay fever has become increasingly common. In 2024, hay fever affected 10–40 percent of the world's population. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988−1994), which collected information from nearly 40,000 people in the United States, showed that 26.9 percent and 26.2 percent of the population were allergic to perennial ryegrass and ragweed respectively—percentages at least twice as high as in the previous survey (1976−1980).

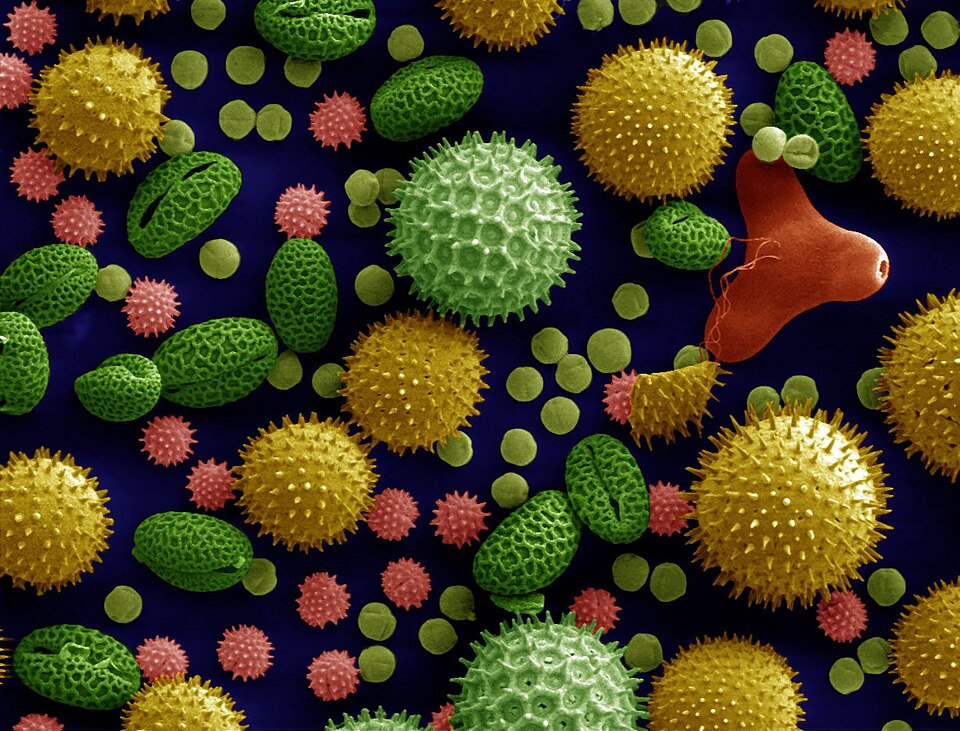

It’s the pollen that’s to blame for allergy symptoms. Plants must join sex cells to reproduce. Pollen carries the male sex cells, so it must be transferred to the female plant in some way. Many plants use insects, such as bees, to transfer their pollen to other plants, while others rely on wind. The plants that are wind-pollinated produce tiny, light pollen that can be carried on a breeze—fantastic for their reproduction, disastrous for our respiration.

The Immune Response and Climate Change

When we inhale pollen grains, they can trigger an immune response in which our body attempts to defend itself against them. Our immune system can overreact to harmless pollen; the sneezing, watery eyes, and histamines that make your nose itchy are designed to kill or eject the pollen. If you’re prone to allergic rhinitis, the more pollen you’re exposed to, the worse your symptoms may be.

Not every hay fever sufferer is allergic to every pollen. It tends to be seasonal: In the spring, tree pollens like those from the birch, oak, and mountain cedar cause the most problems, followed by grass and weeds like mugwort and nettle in the summer with weeds like ragweed (the leading cause of hay fever in the U.S.) and fungus spores following in autumn.

However, the primary factor, climate change, impacts hay fever throughout the year. Climate change can increase the release and potency of certain types of pollen, leading to more severe hay fever.

In 2015, the World Allergy Organization, a group comprising 97 medical societies from around the world, released a statement warning that climate change would impact the timing, duration, and severity of pollen seasons.

“The strong link between warmer weather and pollen seasons provides a crystal-clear example of how climate change is already affecting people’s health across the U.S.,” said William Anderegg, a biologist at the University of Utah, about his team’s research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2020.

“A number of smaller-scale studies—usually in greenhouse settings on small plants—had indicated strong links between temperature and pollen,” notes Anderegg. “This study reveals that connection at continental scales and explicitly links pollen trends to human-caused climate change.”

Warmer Weather Means More Pollen

The first culprit is the rise in temperature caused by climate change. Compared to previous decades, plants now bloom earlier and produce pollen for a more extended period of the year. According to Sanjiv Sur, MD, director and professor of Allergy and Immunology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, “There’s no question [that] as there’s global warming, the pollen season is increasing.”

A 2015 study published in Global Change Biology showed that, between 2001 and 2010, the U.S. pollen season started on average three days earlier than it did in the 1990s. A 2024 article by the Association of American Medical Colleges stated that over the past several decades, the pollen season has extended by as much as three weeks in some areas of North America. What’s more, the Global Change Biology study found that the amount of airborne pollen increased by more than 40 percent. “These changes are likely due to recent climate change and particularly the enhanced warming and precipitation at higher latitudes in the contiguous United States,” concluded the researchers.

This may also be contributing to the increase in people suffering from hay fever. One estimate predicts that by the 2050s, that number will reach four billion.

Pollen Problem Fueled by Carbon Dioxide

While warmer temperatures have led to earlier and longer pollen seasons, as well as more potent pollen, rising carbon dioxide levels are also contributing to plants producing more pollen. Plants feed on carbon dioxide, so when there’s an abundance of it, they can go wild, producing pollen. This, coupled with warmer temperatures, is ideal for plant growth and reproduction, which means more allergens for us.

Take, for example, the invasive and highly allergenic plant ragweed. In 2000, Lewis Ziska, an expert on climate change and its impact on plants, led a research team at the U.S. Department of Agriculture that grew ragweed in the lab under three conditions: pre-industrial levels of carbon dioxide, current levels, and the higher levels expected in the 21st century. They found that exposure to current levels increased the amount of pollen the ragweed produced by 131 percent compared to pre-industrial carbon dioxide levels. Under predicted future carbon dioxide levels, it skyrocketed to 320 percent. The researchers concluded that, “the continuing increase in atmospheric CO2 could directly influence public health by stimulating the growth and pollen production of allergy-inducing species such as ragweed.”

Ziska says the intensity of an allergic reaction depends on the amount of pollen released, the duration of exposure, and the allergenicity of the pollen. In ragweed, these three factors work strongly together. “What’s unique about ragweed is that it produces so much pollen—roughly a billion grains per plant,” he wrote in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives in 2016. “And the Amb a 1 protein [in the pollen coat] is also highly reactive with the immune system.”

No Escape for the City

Though it might seem that hay fever would be less of a problem in the city, away from all the trees and weeds, the opposite appears to be true. Similar results have been observed outside the lab: In downtown Baltimore, where it’s 3˚C warmer and contains 30 percent more carbon dioxide than the countryside, ragweed “thrived, growing bigger and puffing out larger plumes of pollen than its country counterpart,” reported Rachel Becker in The Verge.

Ragweed may thrive in our cities, but there’s a bigger—and taller—problem: The trees planted to provide shade and beauty are making our allergies worse.

“Many people believe that the more trees you have in a city’s green infrastructure, the more they act as a biofilter,” said Amena Warner of Allergy UK, as reported by The Ashland Chronicle. “But are they the right kind of trees? In urban areas, particularly in London, there’s a lean towards planting birch trees, which are highly allergenic. When they’re in cities, people can’t escape the pollen easily, and it’s virtually indestructible unless it’s wet.”

That means the pollen that collects on your clothes, on the bottom of your shoes, and in your hair during your afternoon stroll could plague you until it rains or is washed away. That, says Warner, extends the time you’re in contact with pollen, even out of pollen season. The UK has the third-highest rates of allergic rhinitis and asthma prevalence globally, which is why Allergy UK is deeply concerned about this issue.

“It’s important that the right tree is planted in the right place,” said Warner. “We want to raise awareness of why planting allergenic birch trees in urban areas can increase hay fever and other respiratory conditions.”

So, if we know that pollen from birch trees (and many others) causes allergic reactions, why are they still prevalent on our city streets? “Mainly because they seem to be fashionable,” said Warner. “They have this lovely silvery bark, and they’re long and graceful with a beautiful sweeping canopy that gently sways in the wind. And they don’t drop fruit—in a city, you want trees with a low cleanup cost.”

Keeping Hay Fever at Bay

There are alternatives; not all tree pollen is allergenic. In 2010, a report by the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) called on states, communities, and homeowners to “undertake smart community planning and landscaping with attention to allergenic plants and urban heat island effects to limit the amount of pollen and other allergens that become airborne.”

One way to mitigate the impact of hay fever in cities would be to utilize the Ogren Plant Allergy Scale (OPALS), which rates trees based on allergen level. When choosing your tree, whether it’s in your garden or on the street, opt for a low-allergen variety that won’t trigger sneezing.

As the climate continues to change and we see an increase in hay fever, we’ll also notice a bigger impact on public health, not least because an estimated 30 percent of people with allergic rhinitis develop asthma later on. While urban planning may be beyond our control, there are some steps we can take to mitigate the pollen problem.

David Mizejewski, a naturalist at the NWF and a long-time allergy sufferer, offers some advice:

- Get an allergy test—that way, you can decide when it is best to go outside

- Ask your doctor about allergens and what medication to take

- Check daily pollen counts and go out when they’re low

- Wash your clothes and yourself to remove trapped pollen, and use nasal sprays

- Choose non-allergenic plants for your garden

- Plant female trees and shrubs (it’s the males that produce pollen)

It’s important to remember that people with allergic rhinitis can develop asthma, which can be serious. So, if your symptoms start to affect your breathing, it’s best to consult a doctor.